Climate change is complicated; sea level rise is not. We live on an Island — a glorified sandbar — and the sea is closing in on us. It is rising much faster than anticipated. In the last century sea level rose by about a foot. In this century, due to human-induced global warming, it is expected to rise at least five feet, according to a new report by the international Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program.

Just last week the mainstream sea level rise estimate was three feet, but the new five-foot number takes into account the accelerated rate of melting by glaciers, ice caps and the enormous Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets. Some specialists think even that estimate is low.

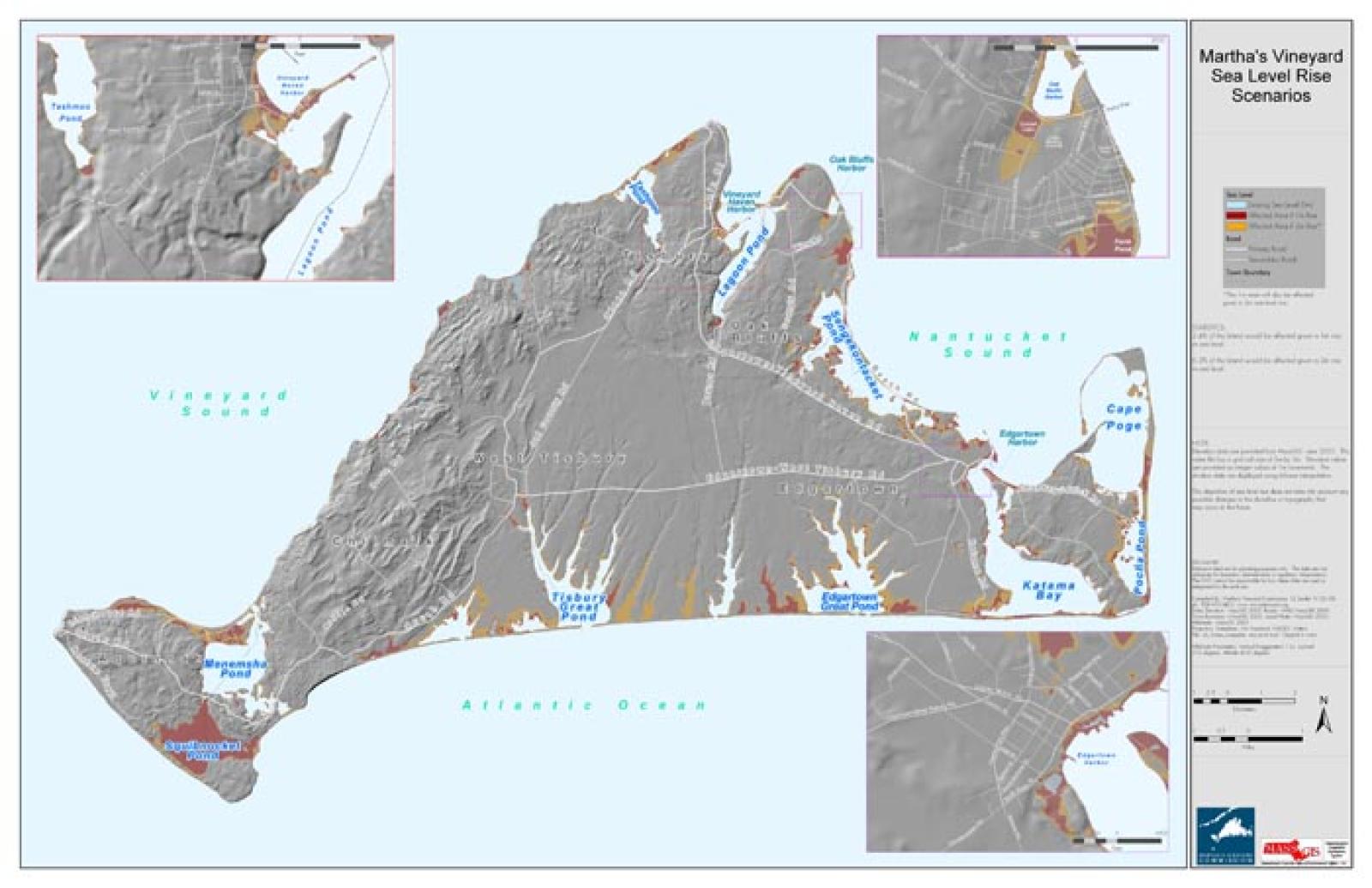

On the Vineyard a five-foot rise in the sea will swallow whole swaths of low-lying land — beaches, salt marshes, roads and homes. Five Corners in Vineyard Haven will disappear, as will portions of downtown Edgartown and Oak Bluffs.

The land surrounding our many majestic coastal ponds will be under water, including the shores of Chilmark and Edgartown Great Ponds, Sengekontacket and Trapp’s Pond, Farm Pond, Sunset Lake and Squibnocket Pond. South Beach, Katama Point and vast portions of the Chappaquiddick shoreline will be lost to the sea. Much of Lobsterville will cease to exist, as will at least half of the Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary.

Sea level rise will be the most drastic of all climate change impacts on the Vineyard. It will literally change the face of the Island and it will do so within the lifetime of living Island residents.

Coastal geologists Orrin H. Pilkey and Rob Young make this abundantly clear in their book, The Rising Sea. “Of all the ongoing and expected changes from global warming . . . the increase in the volume of the oceans and the accompanying rise in the level of the sea will be the most immediate, the most certain, the most widespread, and the most economically visible in its effects,” the authors write.

Too many reports on sea level rise end with the term “by the end of the century.” This is misleading. The sea will not suddenly rise in the decades to come — it is already doing so. Stephen McKenna, Cape and Islands regional coordinator of Massachusetts Coastal Zone Management, believes that the time frame for sea-level rise will be sooner than 100 years. “Much sooner,” he said.

Southern New England will see an above-average impact from sea level rise because the land beneath our feet is sinking. “Massachusetts is subsiding so sea level rise is higher than the mean,” Mr. McKenna said.

The Union of Concerned Scientists notes that the counties along the Massachusetts coastline are home to 75 per cent of the state’s population. “From critical infrastructure to waterfront homes to salt marshes, much of this coastline is exceptionally vulnerable to sea-level rise. Indeed, some major insurers have withdrawn coverage from thousands of homeowners . . .” the scientists write.

Islands in their natural state can adapt to rising seas. Shorelines naturally migrate inland and readjust. Not so when humans develop the coast, as we have done here for generations. Roads, homes and businesses are now built upon and around the ever-changing shoreline. The Island is a beach resort community; our economy is inseparably and precariously linked to the value of our coastline.

Sea level rise will affect the physical Island environment in many ways: the permanent loss of low-lying land, increased coastal erosion and flooding, increased damage due to storms and storm surges, and the intrusion of salt water into low-elevation water wells and septic systems.

Sea level rise will exacerbate coastal erosion. Large swaths of Wasque and Lucy Vincent beaches are washing away daily. Unlike some states, Massachusetts does not allow the mining of ocean sand to replenish beaches and protect uplands. And like the unprecedented number of recent worldwide floods, tsunamis, hurricanes, earthquakes and tornados, local coastal erosion is not an anomaly, it is the new norm.

Coastal banks, small and large, private and public, will erode and threaten the land, homes, and roads above them. Historic and aesthetic attractions such as the Gay Head Cliffs and East Chop bluff are at risk. “Local erosion rates in the last three winters have been dramatically higher than we’ve seen previously. It reflects a trend of erosion rates due to climate change, relative sea level rise and storm frequency,” Mr. McKenna said.

Coastal erosion will send more sand sediments into the ponds and require more dredging to protect pond water quality. On the plus side, those sediments can be dredged from the ponds and placed back onto beaches, but dredging is extremely expensive and requires grueling state and federal review.

Coastal flooding will devastate shoreline roads and homes. Flooding will expand well beyond the 20-year-old FEMA designated flood zones. Where will all the water go? Flooding will increase stormwater runoff and pollution into the coastal ponds; it will overrun roads, flood buildings and basements, and increase the prevalence of asthma and allergy-inducing mold.

Higher seas mean larger storm surges will wash ashore and cause more damage to structures — and humans who get in the way — as waves break apart buildings and send storm debris flying about in wind and waves. Public health and safety officials are put at risk when forced to rescue and evacuate residents who are in harm’s way. It is no small expense for towns to clean up after storms — to repair roads, pump floodwater, rescue damaged boats and repair marine infrastructure, assist homeowners with repair projects, fix bike paths and beach parking lots and other amenities that the seasonal residents expect.

As salt marshes shrink, so will their value as flood retention basins, pollution filters and nurseries for shellfish and finfish. How do you place an economic value on all that salt marshes provide? And with homes lining the inland pond shores, there is little land available for marshes to naturally migrate inland.

Northeasters are a fact of life here. Hour by hour, for days at a time, they chip away at our natural and manmade infrastructures. Hurricanes, on the other hand, are not the norm. But warming seas make the likelihood of a major hurricane in southern New England ever more likely. There is no room for complacency; we need to take hurricane warnings seriously.

A less obvious impact of sea level rise is the intrusion of salt water into low-lying private fresh water wells and septic systems. Bill Wilcox, water resources planner for the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, points out that this is already a problem in outlying residential areas such as Katama and Chappaquiddick. “As the sea level rises the water table will rise, meaning more interface between fresh and salt groundwater,” Mr. Wilcox said. He added that increased sodium levels in water can result in diseases such as high blood pressure.

Sea level rise is bad news for Island dwellers worldwide. There are three basic options for adaptation:

• Armor the coast to hold back the sea: Protect the structures, roads and coastal banks by building seawalls and revetments to keep the sea at bay. (But these hard structures deflect wave energy, washing away beaches and eroding adjacent land.)

• Accommodate the sea, (at least in the short term): Try to keep using the land — nourish and build up the beaches and dunes, elevate buildings and enforce stronger building codes. Try to avoid impending impacts by acting sooner rather than later.

• Retreat and move out of harm’s way: Abandon low-lying areas and let nature take its course.

The answer for the Vineyard will be a combination of all three options, and every decision will be painful, expensive and politically charged. Entire neighborhoods are at stake. The desire of private property owners to protect their homes will clash with the need to protect public health and safety, to preserve the common good. The challenges for the Island are immense and immediate. And the longer we wait, the more expensive adaptation measures become.

The value of coastal tourism dollars to the state is enormous, but our value as a regional economic force will fade as the sea devours our shoreline. And the importance of seasonal, recreational communities will diminish further when coastal cities like Boston and New York — capitals of business and commerce — begin to feel the effects of sea level rise, when subway systems flood and sewage systems overflow regularly, when major commuter highways are routinely underwater.

Authors Pilkey and Young explain: “When our main population centers are truly threatened . . . small beachfront communities are likely to become declining public priorities. The end result, decades from now, but certainly within this century, will be abandonment of many island tourist communities and, unfortunately, massive seawalling of others.”

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, it is urgent for coastal communities “to begin the process of adapting to sea level rise not because there is an impending catastrophe, but because there are opportunities to avoid adverse impacts by acting now, opportunities that may be lost if the process is delayed.”

Two years ago in their book, authors Pilkey and Young proposed that for planning purposes a seven-foot sea level rise should be assumed. “It is our belief that coastal management and planning should be carried out assuming that the ice sheet disintegration will continue and accelerate. This is a cautious and conservative approach,” they wrote.

We live on an Island — a body of land surrounded by water — and the sea is rising. We need strong, cooperative, Islandwide leadership and political will to face the challenges. This is the biggest threat the Island has ever faced. It’s time to take our collective heads out of the sand — before it disappears.

Liz Durkee is the conservation agent for the town of Oak Bluffs. This is the second part in an occasional series she is writing for the Gazette Commentary Page about climate change and what it means for the Vineyard.

Comments

Comment policy »