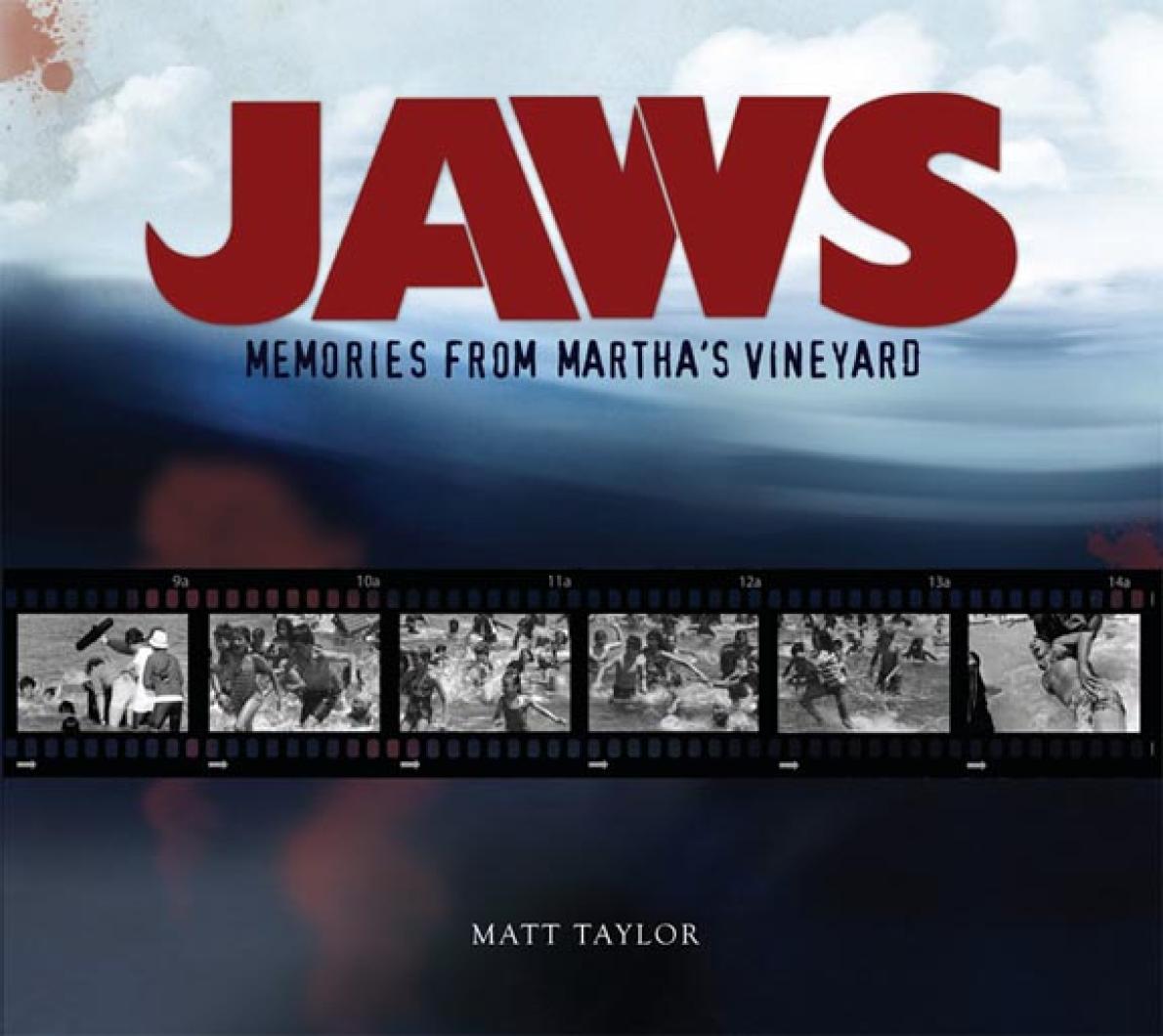

Much has been said and written about the filming of Jaws and its impact in the spring and summer of 1974 on a still relatively obscure fishing and agricultural tourist redoubt seven miles off the southeast coast of Massachusetts. After Jaws: Memories from Martha’s Vineyard there is simply nothing left to be said. A staggering compilation of mostly unseen photographs and artifacts, as well as hundreds of interviews with the Island and Hollywood denizens who conspired to produce the archetypal modern blockbuster, the book is the last word on the subject.

For West Tisbury’s Matt Taylor, who has spent 15 hours a day, seven days a week for the past three years delving into the surreal episode in the Island’s history and compiling the exhaustive work, the movie has an impact on his life familiar to frightened filmgoers.

“I haven’t been to the beach in three years,” he laughed in a conversation with the Gazette.

As Mr. Taylor details in the book, the Vineyard was once nearly spared “Hurricane Hollywood.” On a location scouting trip to Nantucket in December 1973 production designer Joe Alves was thwarted en route, his ferry turned round by a snow squall. When he returned to Woods Hole and saw that ferries were still departing for Martha’s Vineyard he recalculated his itinerary and found in the Vineyard an ideal haven for a mechanical shark to come wreak havoc.

Although the Vineyard was selected almost by accident, the impression its lively and idiosyncratic inhabitants left on the picture was indelible. To Vineyarders, largely dismissive of what they felt was a B-movie caravan passing through their community, the lure of stardom figured less in their participation in the movie than the promise of $75 a day during the height of a recession. Quint, the iconic, half-crazed, Narragansett-chugging harpoon fisherman played by legendary character actor Robert Shaw, although partly inspired by Montauk sportfisherman Frank Mundus, increasingly took the form and manner of the sort of sui generis characters only the Vineyard could produce.

As Mr. Taylor writes, “Filmmakers were faced with the challenge of transforming the English-born actor into a blaspheming Yankee fisherman.” To that end Craig Kingsbury, a “Prohibition-era rumrunner, prizefighter, blacksmith, fisherman, farmer, landscaper, artist, environmentalist, shellfish warden and, eventually, Tisbury selectman,” who regarded the Hollywood set as “perverts, drunks and batty as hell,” was recruited by Steven Spielberg to spend as much time as he could with Mr. Shaw, introducing him to the unique idiom and character of the place.

The two got on famously, and as Karen Colaneri of West Tisbury recalls of her mother, a production secretary on the film, “She always said that it was quite a sight to see the two of them walking together down Main street in Edgartown like two drunken sailors, half in the bag and laughing like hell.” Some of Mr. Kingsbury’s more unusual turns of phrase were incorporated verbatim by screenwriter Carl Gottlieb (“It looks like a kiddy’s scissor class has cut it up for a paper doll.”)

In his research Mr. Taylor discovered that Mr. Kingsbury was not the only Islander to leave his stamp on the Englishman.

“Lynn Murphy had an enormous influence on the way Robert Shaw portrayed the character Quint, and that’s something no one has ever heard for 35 years,” he said of the legendary marine mechanic, whose reputation for mechanical skill is matched only by his well-known temper. Mr. Murphy spent more time on the film than any other Islander, eventually learning to tame the notoriously fickle Bruce, the shark, in his many robotic iterations, using his lifetime’s experience on the water as a guide.

“The sea-sled shark was just another scallop dredger as far as I was concerned,” he says humbly in the book.

“Interviewing people in Hollywood, almost every single one of them across the board said to me, ‘If it weren’t for Lynn Murphy Jaws probably never would have seen the light of day,’” Mr. Taylor said.

But Mr. Murphy’s influence extended beyond special effects.

“As the story goes, Robert Shaw was having difficulty one day with how to deliver one of his lines. As he was speaking to Spielberg about this, Lynn was in the background hollering at one of the crew members about an anchor line or something, totally losing it, and Steven stopped Robert and said ‘You hear that? That’s how I want you to sound. From now on Lynn is Quint.’”

“I had already been thinking that before [Lynn’s wife] Susan told me that story, because I’m sitting there doing these interviews with him and thinking, boy, he sounds awful familiar.”

Invariably the cosmopolitan Hollywood crew became enamored of the peculiar race of Vineyard fixtures, such as Menemsha lobsterman Donald Poole.

“Spielberg just fell in love with him,” Mr. Taylor said. “He must have been well into his 70s when Jaws was filmed and Spielberg thought him to be so picturesque with his pipe and his old salty mannerisms that he cast him as the Amity harbormaster.

“Each day during lunchtime after directing the shots with all these locals, Spielberg would go and sit in the truck with Donald Poole and eat lunch with him and ask him about the old days and what it was like to be a Menemsha fishermen. This went on day after day, and after the third or fourth day somebody came up to Donald Poole and said, ‘Why is it that you get to spend so much time with Steve Spielberg?’ Poole looked at him kind of blankly and replied, ‘Who the hell is Steve Spielberg?’”

As Mr. Taylor says, the story is “typical of the distant and aloof way Islanders tend to be towards off-Islanders.”

Hundreds of similar stories are available in the book, which is the first to document the making of the movie in the order of its production schedule. To chronologically compile the material, including hundreds of photos donated by Lynn and Susan Murphy, Mr. Taylor spent countless hours cross-referencing photos and notes with articles from the Gazette’s archives, as well as a yellowing original production journal fortuitously unearthed by Mr. Gottlieb that covered most of the movie’s third act at sea.

“Without the old Gazette articles documenting that portion of the production, I was kind of lost. Then, lo and behold, one night in January of 2010, I got a phone call from Carl Gottlieb. He began the phone conversation by saying, ‘Matt, I’m about to make you a very happy man.’”

Mr. Taylor consciously avoided reading the few books that had been written about the production of Jaws, and the result is a work that is wholly original and comprehensive.

“I knew there were so many more stories that locals had about the production that had never been heard before,” he said. “As it turned out, there were hundreds and hundreds of them — with photos.”

Jaws: Memories from Martha’s Vineyard will be released exclusively on the Vineyard on July 2 and nationally on Sept. 15. It comes in softcover and a hardcover limited edition featuring a DVD of behind-the-scenes production footage as well as an actual piece from the Orca II ship used in the movie, contributed by Lynn and Susan Murphy.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »