You step off the airplane and the hustle

begins. This is Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Bags are temporarily possessed by throngs of porters pushing for tips. Then we are off in a pickup truck with our hosts Margaret Penicaud from the Vineyard, who heads up the Haiti Fish Farm Project here, and Margo Barnes.

It has been 15 months since my last visit and these are my impressions, two years after the devastating earthquake that claimed tens of thousands of lives.

The country appears noticeably better this time; the mounds and mounds of debris we witnessed last year are not gone but vastly reduced. The ever-present Tyvek shacks are not as obvious; large tracts on outlying hillsides have been converted to permanent plywood-and-tin-roof houses. There is a nearby hand-operated water pump where residents line up with five-gallon buckets. Sixty miles north of Port-au-Prince, over Goat Mountain, we are on a gravel road passing donkeys and their riders as they cross a river. Women wash their clothes and bathe in the river. We arrive at a 17-acre, state-of-the-art hospital funded by Partners in Health that will open in June for Haiti’s poor.

I see parking lots full of idle U.N. vehicles. Dozens of Mack trucks, most of them 30 years old, line up at quarries for gravel. School children arrive at their grammar school full of smiles and laughter, wearing bright pink and blue uniforms, the girls with yellow ribbons in their hair. I approach and they touch my hand. Desperation has subsided, the sorrow not as obvious. Then you go into the homes and hear about all the loved ones lost.

I ask several people what they think of President Michel (Sweet Mickey) Martelly. They say that they are beginning to see some stability and a return to normalcy.

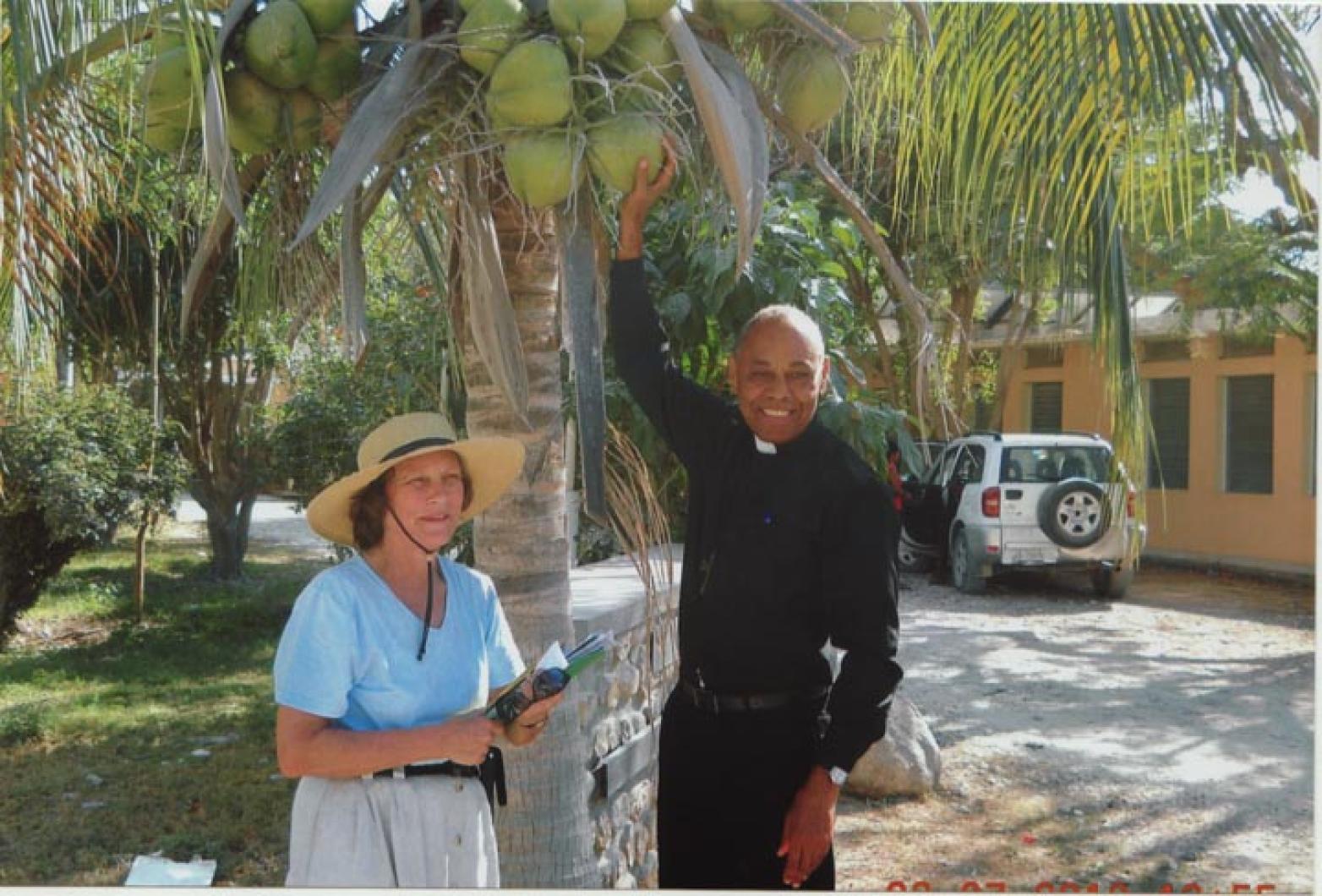

I have the good fortune to meet the archbishop of Haiti, Guy Poulard. I press him for his opinion on the president. “A good musician,” is his answer. The archbishop is a good diplomat, I think to myself.

We see crowds of young men on new motorcycles built in China. Bougainvillea blooms drape themselves over fingertip-high cement block walls. In Port-au-Prince, For Sale signs adorn trucks — unheard of the last time we were here. And vendors! There are street vendors selling everything. Tap-tap drivers in their brightly-colored mini busses have no tolerance for Americans taking candid pictures. Dust clouds hang in the air like the morning fog at Katama.

The sight of rebar is everywhere; it hangs off the back of a pickup truck creating sparks as it drags down the street, and at construction sites it reaches for the sky like so many towers. Digicell, voila.

All this sawing, nail banging and trowel scraping reminds me of the Vineyard for most of the last decade, when you couldn’t separate an Island plumber from his client for love or money. Unlike this decade.

My advice to those plumbers: Go to Haiti.

Al Colarusso lives in Vineyard Haven.

Comments

Comment policy »