There is an inherent danger in reading the essays and books of Edward Hoagland. Suddenly, nothing else compares. Not just other books or other writers, but real life too. The phone rings unanswered, e-mails amass with no reply, and social engagements are shrugged off with little to no guilt. When under the spell of Mr. Hoag-land’s prose, the rest of us talkers or writers become toddlers, mere fumblers of language just embarking on our ABC’s.

Hyperbole? Consider a random sentence plucked from Mr. Hoagland’s latest book, Alaskan Travels arriving in bookstores this month. The book is thrown in the air and lands on page 140.

“Now naturally the center of attention, he was a white-haired, low-keyed man with a face that appeared much rearranged by the process of living — a much-traveled, practiced face.”

Mr. Hoagland is describing here a man named J.D. Langston, an Exxon Vice President for Exploration USA, whom he was interviewing for a story about oil exploration and newly minted Alaskan millionaires for a Vanity Fair article. The interview took place in the 1980s, when Mr. Hoagland made three long trips to Alaska on assignment for the magazine as well as for House and Garden. But the real reason for his journeys to Alaska was love.

“I was early fiftyish, mired in a deteriorating marriage; she seventeen years younger and divorced from a psychiatrist in her home state of Massachusetts — her father an alcoholic ex-CIA operative, her brother a golf pro . . . . She [Linda] was in charge of the nursing care of all the tuberculosis patients in the state,” he writes in the opening of the book.

Mr. Hoagland traveled to the farthest reaches of Alaska, a state he refers to as “that top hat of the continent,” accompanying Linda on her rounds. In his book, he describes a place of both beauty and despair, filled with indigenous populations, homesteaders and all manner of misfits looking for a new start.

“Furious-looking young oil-rig employees with lop-sided hands, pugnacious moustaches, and misfit beards jostled brush-cut military noncoms dragging duffel bags, and the occasional sidelong glare indicated that certain passengers weren’t used to being stuffed next to other people like this at all and were going to Alaska precisely to prevent it.”

In Mr. Hoagland’s hands this picture is not pretty, the poverty and alcoholism so extreme one begins to reconsider Prohibition as a sound idea. But he does not rub the reader’s nose in the despair. As in all of his essays and books, Mr. Hoagland reveals the whole teeming lot of humanity, giving an infantryman’s eye view, waist deep in the muck, of how life is really lived. Somehow, what he conjures up always turns out to be beautiful, not in the scenic tour sense, but in the unflinching, honest way he portrays people and their circumstances.

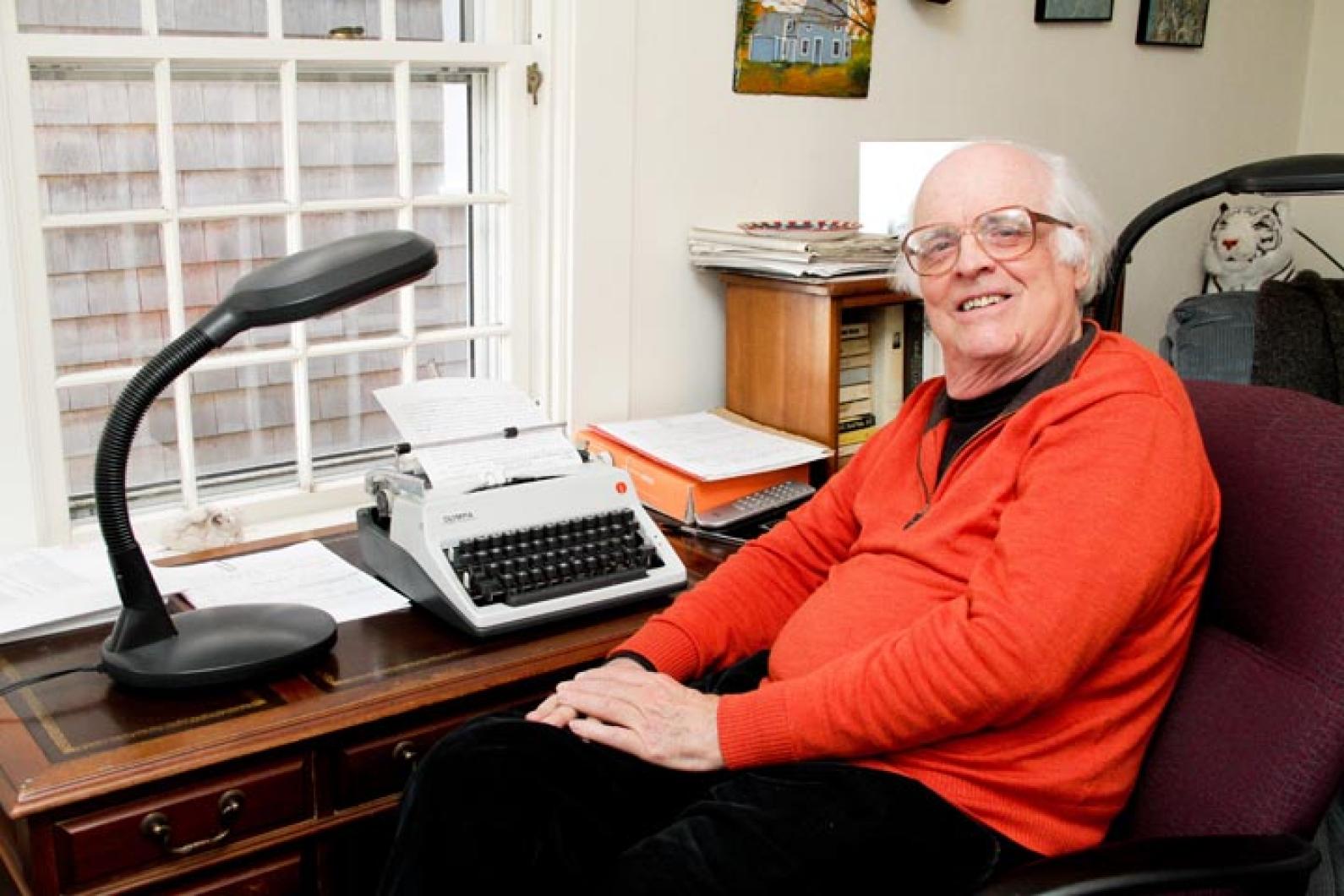

“I often describe myself as a rhapsodist,” Mr. Hoagland said in an interview at his home in Edgartown. At 79-years-old, he is not traveling the globe nearly as much and divides his time between winters on the Vineyard and summers spent at a cabin in Vermont with no electricity, plumbing, phone lines or cell phone reception.

“I have a Whitman, Emersonian love of people. God is energy and the Big Bang is still in our smiles,” he said, then paused and continued, “and in our destructiveness too.”

Mr. Hoagland grew up in New Canaan, Conn., the son of a prominent lawyer. Early on he realized this life of privilege was not for him, and as a young man he literally ran away and joined the Ringling Brothers Circus. These adventures formed the basis of his first book, a novel called Cat Man, written while an undergraduate at Harvard.

Mr. Hoagland made the mistake of showing an early draft to his father who then tried to use his influence as a lawyer to stop the publication of the book, worrying that his son’s use of some slight swear words might damage the family name and ruin his sister’s chance of marrying into a good family.

Eventually the book was published while Mr. Hoagland was in the army and he only learned of its highly praised reception from one of his superior officers, who approached him and asked, “Private Hoagland, did you know your picture is in Time Magazine?”

Two more novels followed, one set in a New York city welfare hotel, a place Mr. Hoagland called home for many years while trying to make a living as a writer.

While doing research in British Columbia for a fourth novel, Mr. Hoag-land had an epiphany. He realized his notes and journals were so good that he did not have to create a fictionalized world, and he turned to nonfiction. There was another reason, though, for this switch. He had always dreamed of writing the Great American Novel, and although his three novels were well received, he had begun to doubt he was capable of truly great fiction.

“I didn’t have the imagination to be a great novelist,” he said. John Updike was a friend as was Paul Theroux. “They have memories that are not microscopic but massive.”

Mr. Hoagland first met Mr. Theroux in London in 1967. “He can still remember the suit I wore when I first met him,” he said.

He found he could also write nonfiction faster than fiction, “from 10 words an hour to 20 words an hour.”

After turning to nonfiction writing, Mr. Hoagland immediately established himself as one of America’s most prominent essayists. Alaskan Travels is his 22nd book.

Mr. Hoagland has also taught writing at various colleges throughout his career. His mantra for his students was to write about what they love, a corollary to the old adage to write what you know. Mr. Hoagland practices what he preaches.

“I love tugboats, I love turtles, I love mountain lions,” he said, referring to subjects he has written about extensively. And when Mr. Hoagland loves something it is not from a distance. Consider his experience with a mountain lion he fell for while working at The World Jungle Compound in Ventura, Calif., where film studios kept their movie animals. The mountain lion was a fully-grown pregnant female, one of the many MGM kept on its film lot. One day, on impulse, Mr. Hoagland decided to enter the cage.

“I was on all fours, it [the cage] was low,” he remembered. “Then she sprang at me, thrust her paw to my face. Her paw was as large as my whole face, but she kept her claws in. That’s why I still have a face.”

Mr. Hoagland credits some of his success as an essayist to his stutter, something he has struggled with for his whole life.

“I used my stutter as best I could. I used it to learn how to interview people.”

His stutter forced him to listen rather than interrupt the flow of someone else’s words. It also helped form his view of the world as an outsider, never fully comfortable with his oral presentation. This standpoint reveals a large piece of the puzzle of what makes him such a great writer.

Case in point, midway through the interview, Mr. Hoagland talked about how he interviews his subjects.

“I get people to talk about what they care about,” he said. He gave some examples of what he might ask a subject; about their work, their life and then he turned his gaze on the interviewer.

“I know you have children so I would ask you about them,” he said. Then he did begin asking questions, just a few, but in the shift from for-instance to in-the-moment, the entire energy of the room shifted also. Mr. Hoagland’s focus became so acute in its curiosity and empathy it was as if he had placed his heart on the table in solidarity. This was no reporter’s trick, either, no ruse to get one to talk. It was fully genuine, just a natural extension of a man who says, “I love rubbing shoulders with the masses of people.”

It also revealed that extra gear, the unquantifiable one, of why Mr. Hoagland has always been, and will always be, at the top of his craft.

Comments

Comment policy »