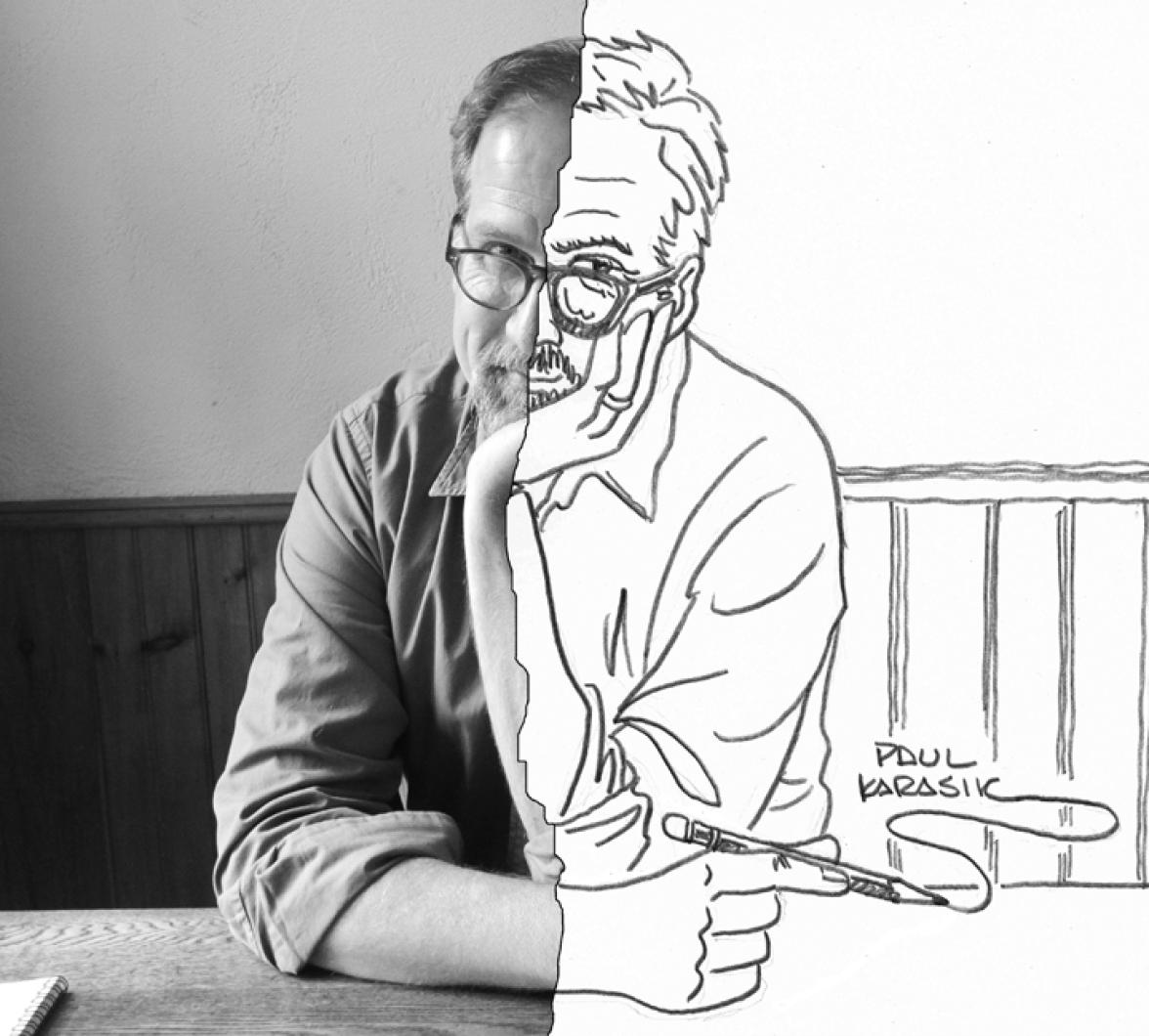

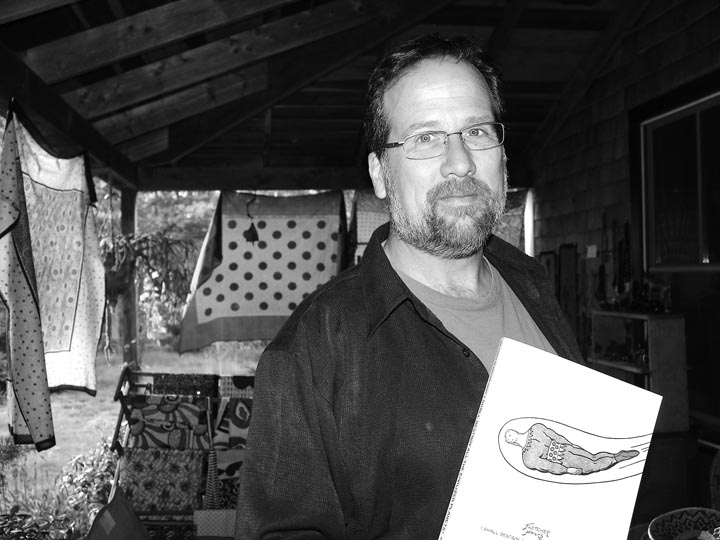

Paul Karasik takes cartoons seriously. Take a gag cartoon from the vault of Ernie Bushmiller’s much-loved Nancy strip, for instance. The three-panel cartoon is not so much read by Mr. Karasik as absorbed.

As with most of Mr. Bushmiller’s strips, the cartoon is stripped to its most fundamental elements, not a line is wasted. In the first two panes, the scalawag Sluggo drenches neighborhood children with his six-shooter squirt gun. Nancy observes the rampage silently, waiting in the final pane as Sluggo approaches. Her squirt gun is affixed to a garden hose, a fact concealed by a stockade fence.

“DRAW, YOU VARMINT” Sluggo says menacingly, his comeuppance administered in an imagined fourth pane. While the strip was perhaps intended to draw a chuckle over a bowl of cereal, for Mr. Karasik it elicits something closer to reverence.

“Everything you need to know about reading, making and understanding comics can be found within the three panels of a simple comic strip from August 8, 1959 — this strip,” he said on Monday at his house in West Tisbury.

Mr. Karasik lingers over the word bubble, DRAW, YOU VARMINT.

“Even the lettering is . . . perfect,” he said.

Mr. Karasik, an Eisner-award winning cartoonist himself whose work has appeared many times in the New Yorker, has dutifully obeyed Sluggo’s command since childhood, when he would devour the Sunday Washington Post comics section, its colorful pages festooned with the classics: Peanuts, Little Orphan Annie, Dick Tracy, Steve Canyon and, of course, Nancy. But the work of Mr. Bushmiller was unappreciated, even scoffed at by Mr. Karasik and his elementary school classmates for its simplicity and utter lack of cynicism. Now Mr. Karasik knows better.

“He is a master cartoonist who’s work has been largely overlooked and only taken seriously by a handful of the cognoscenti,” he said with an almost comic gravity.

Mr. Karasik is currently in the fourth year of a project that seeks to deconstruct and elucidate the mechanics of that perfect Nancy cartoon. Along with fellow cartoonist Mark Newgarden, Mr. Karasik is expanding his seminal paper, How to Read Nancy (required reading in cartooning programs) to a full-length book that comprises more than 40 chapters so far, each concentrating on a particular aspect of the August 8, 1959 strip; from the facial expressions, the dialogue, and the placement of the balloons to the negative space, the lettering, the inditia, the panel size . . .

“I think Ernie Bushmiller would be shocked and mystified, but somewhat pleased, that someone would take his life’s work so seriously,” Mr. Karasik said.

For Mr. Karasik’s students at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he teaches a comic book narrative course each spring, the strip has served as a lodestar for the semester.

“I start out the class with these three panels,” he said. “I used to wait to introduce the Nancy strip halfway through the semester, after they were struggling with how to make comics. But if you spend one hour dissecting this strip and have the students do all the work, they start the year not making mistakes.”

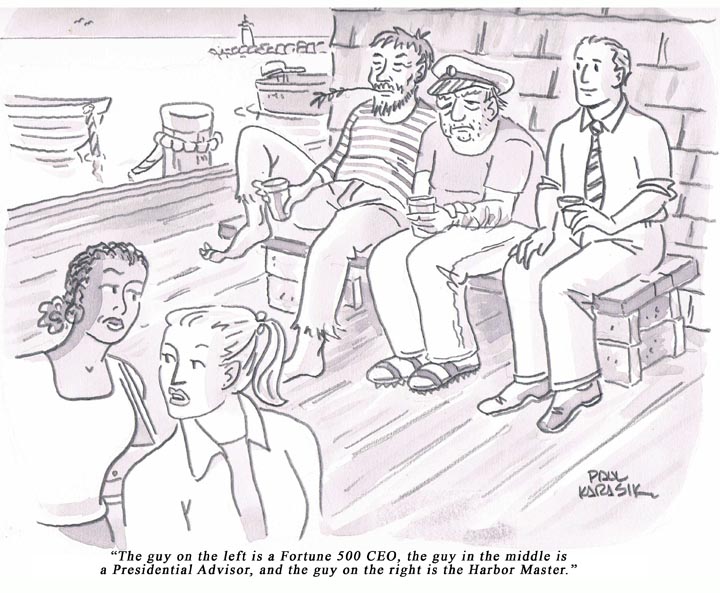

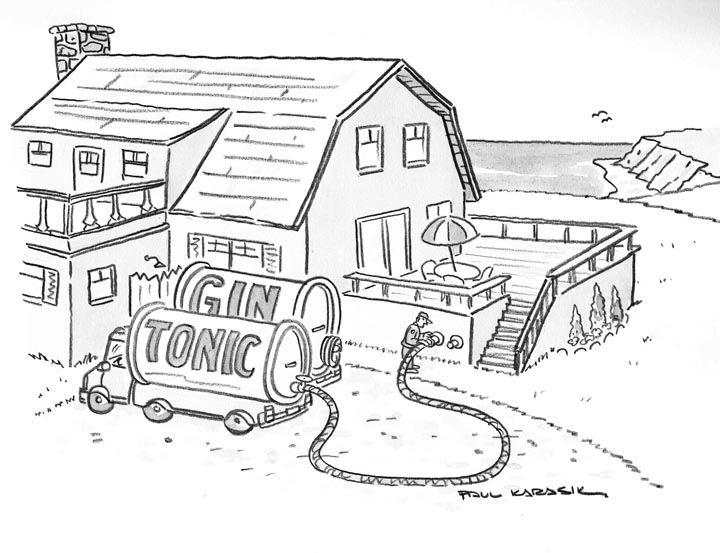

Mr. Karasik said that Mr. Bushmiller was a communicator par excellence, having mastered the visual language of comics, a vernacular with its own grammar and syntax. It is a language to which Mr. Karasik has made his own considerable contributions. Each Saturday morning Mr. Karasik, who serves as the development director at the Martha’s Vineyard Charter School during the week, drafts a batch of 10 comics for submission to the New Yorker. Typically he sells one gag a year, but already in just the past six months he has sold three cartoons. Next Tuesday he will go, in person, to pitch his latest cartoons to the editors at the magazine’s famed Tuesday morning office hours for cartoonists, a holdover from a different era.

“Back in the day when you could make a living as a cartoonist, you could spend a whole day walking around with your portfolio going from Collier’s to Red Book to Saturday Evening Post to the New Yorker trying to sell your gags. Now it’s down to just the New Yorker,” he said.

But Mr. Karasik’s most personal, and most celebrated, work has come outside the confines of the one panel gag. In 1994, along with former Marvel cartoonist David Mazzucchelli, he adapted Paul Auster’s existentialist detective novel, City of Glass, as a comic.

As Mr. Karasik thumbed through the book on Monday, the dauntingly boundless freedom of the graphic novelist became apparent. A familiar nine-panel grid lends a rhythm and meter to the story, but as the main character of the novel’s grip on reality begins to slip, the rigid nine-panel grid slowly begins to disintegrate as well.

“A comic page is like a construction site and the cartoonist is like the general contractor as well as the architect,” he said. “The arrangement and configuration of the panels, as well as the content of panels combine to tell a story, but also can create context and sub-context and even subliminal context. We have more tools to work with than the author, in a sense.”

Mr. Karasik followed City of Glass with another collaboration, this time with his sister, on a memoir, The Ride Together, which recounts their experience growing up with an autistic older brother. The book alternates between his sister’s prose and his own graphic interpretation of this childhood, to offer a parallax view of the family’s experience.

But it was a collaboration with a cartoonist who had been dead for almost four decades that earned him cartooning’s highest prize, the Eisner award. In I Shall Destroy All The Civilized Planets, Mr. Karasik compiled the work of Fletcher Hanks, an all but forgotten WWII-era cartoonist, whose joyless and sadistic protagonist, the superhero Stardust, would dole out righteous retribution to evildoers, invariably rendered as permanently snarling subhumans inhabiting a fever-dreamlike universe.

“It was the first few years of the comic book where really anything goes,” he said. “They didn’t know what was allowed and what wasn’t allowed in a comic book — they hadn’t made up the rules yet. The levels of tension and brutality in these stories is palpable and they’re just really freaking weird.”

Mr. Karasik appended the compilation with a cartoon of his own, illustrating his experience tracking down Mr. Hanks’ son, Fletcher Hanks Jr. who told Mr. Karasik that his father was a wife-beating alcoholic who left the family when the younger Hanks was 10 years old. In one Stardust cartoon the hero is shown freezing a villain for all time to think about his crimes. Mr. Hanks himself, it turns out, froze to death on a park bench in New York city. In Mr. Karasik’s comic at the close of the book, he trenchantly directs Stardust’s retributive justice at the superhero’s deadbeat creator.

But it is his latest project, dissecting Nancy, that he says has been his most demanding. While the medium of graphic novels and cartooning lends itself to invention, and its rules continue to evolve, the essence of the art form is distilled in that one strip from 1959.

“There’s this little Nancy cult that’s been going on for the past 25 years or so. The secret Ernie Bushmiller society. It’s an organization that’s so secret that nobody knows who’s in it,” he said. “By far, I’ve put more work into this book than any other project I’ve ever worked on.”

Comments

Comment policy »