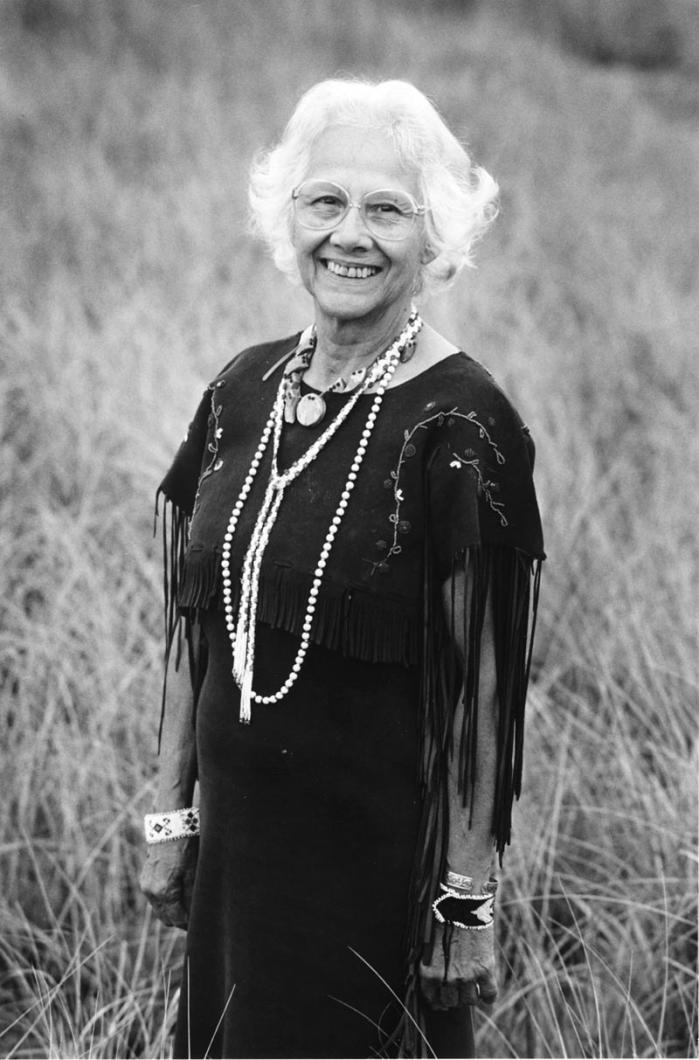

I was moved by news of the death of Gladys Widdiss. She has long been one of my Island heroes, starting with her becoming valedictorian of her senior class at the Tisbury High School in 1932. More recently I admired her for her determination and success in her dealing with the Bureau of Indian Affairs to get the Wampanoag community of the Island recognized as a tribe. “We know who we are,” she used to say. “The challenge was that we just had to convince the bureaucrats in Washington who we are.”

In memory of Gladys, I would like to share a special experience I had with her some years ago. I had invited her to join a class I was teaching on Island history for John Morelli in the adult education program at our high school. I wanted her to be the one to tell us about the Wampanoag community on the Island.

Among those in the class was a retired member of our foreign service, who took upon himself all of his diplomatic skills to get Gladys to tell us a traditional tribal story. He turned out to be no match for her. She stated steadfastly that she was not the storyteller of the tribe. Winona was the one who held that role in the tribe, making it clear to all of us that the stories of their tradition were not just a collection of tales, but an integral part of their identity as a tribe. They could not just be passed off as entertaining. Their recitation was a way of affirming who the Wampanoag people are. She could not just tell us a story.

Toward the end of the class period, our diplomatic friend being firmly held in his place, I asked Gladys not to tell us a Wampanoag story, but to tell us what story she would most like every Wampanoag child on the Island to know. Put in those terms, Gladys turned to us and said “all right, I’ll tell you a story.”

It was the story of Moshup throwing rocks off the shore of Gay Head to create what the English settlers called the Devil’s Bridge. The English settlers recognized the hazard of those rocks as being evil because of their destructive power, as during the wreck of the City of Columbus. But also, in their wish to convert the native population to Christianity, they saw Moshup as the ancient tribal hero, a manifestation of the Great Spirit among them, as demonic.

The story goes something like this: a division arose among the tribe between those who wanted to connect the Island to the Elizabeth Islands and beyond to the mainland by a bridge. Opposed to them was an equally ardent group that wanted to preserve the Island’s separation from the rest of the world and all that represented.

As it happened, the bridge-building faction won out by convincing Moshup to create their desired bridge off the shore of Gay Head across the sound to Cuttyhunk. Great as Moshup was in size and strength, he did not see this as a difficult task.

Those opposed to the bridge were horrified at the prospect and wondered how they could stop it. They went to a wise old woman in the tribe to ask what they might do. She suggested that they challenge Moshup with a condition that he complete the making of the bridge within a single night; that when the cock crowed to announce the dawn, he would have to stop, no matter how far he had gotten in the project. Moshup, given his great strength and energy, thought that he could easily get it completed in that amount of time.

And so on the evening set, Moshup began hurling rocks into the water off the Gay Head cliffs at a furious pace. He worked so fast, those opposed to the bridge feared that it would be completed. They rushed back to the wise old woman with an urgent plea. “What can we do?”

She said to them: “Get a torch and light and wave it in front of the rooster.” They quickly followed her advice and waved the lighted torch before the eyes of the bird. Thinking that he was seeing the first light of dawn, he began to crow.

Upon hearing the cock crowing, the opposition group hastily ran to Moshup and reminded him of his agreement that he had to stop building the bridge at the crowing of the cock. And so it remains to this day no more than the treacherous reef of rocks off the shore of the Gay Head cliffs.

This experience with Gladys remains for me a great moment in my relationship with her. For when push came to shove, the one message that she wanted all the Wampanoag children to know about the institutional life of their tribe is that grandmother knows best.

I will miss Gladys as I cherish the memories of all that she has done and affirmed for all of us who share in our Island community.

— Jim Norton

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »