A group of retired athletes, academics, writers and social activists convened a forum on race and gender in sports here this week, and generally described a bleak landscape for the African American athlete in the 21st century.

The Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School, headed by Prof. Charles J. Ogletree Jr., staged its annual Vineyard forum Wednesday, this year entitled Between the Lines: Race and Gender in Sports in the 21st Century.

With Mr. Ogletree on stage questioning and prodding them, the panelists related their experiences in sports and their observations about the future. Many of the athletes, three of them Olympic medalists, inspired the crowd at the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School Performing Arts Center with personal stories about overcoming adversity, including bigotry.

Wyomia Tyus, the first woman to earn 100-metre sprint gold medals in successive Olympics, spoke of her parents’ influence in helping her navigate a segregated society.

“We knew that’s how life was, this is how people treated you,” she said. “But you never let that get you down. My parents always believed you had to do the best that you could do at all times, no matter the circumstances.”

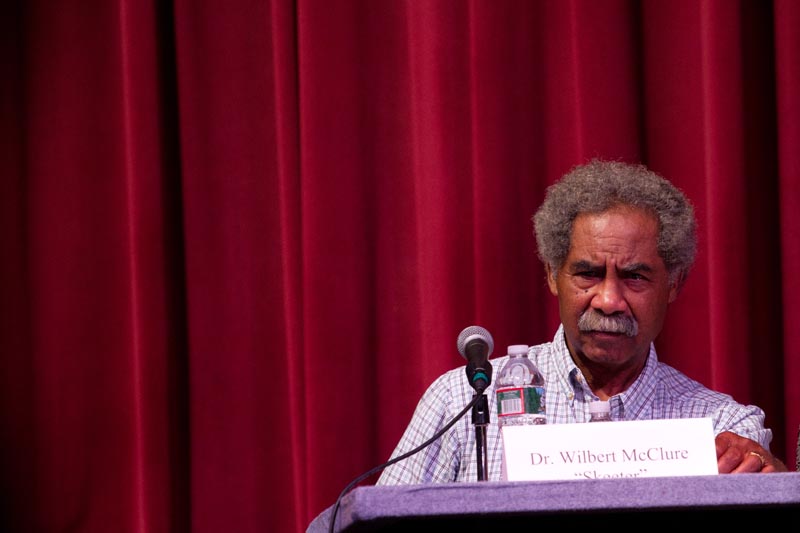

The day-long event included film screenings and what was called a tribute to the legends — including Ms. Tyus; Dr. Wilbert (Skeeter) McClure, a boxing gold medalist in the 1960 Olympics; Philadelphia Judge Jacqueline Frazier-Lyde, daughter of the late Joe Frazier, who herself was a boxer; and Renee Powell, a professional golfer whose father, William Powell, was a black pioneer in building and operating his own golf course in Ohio.

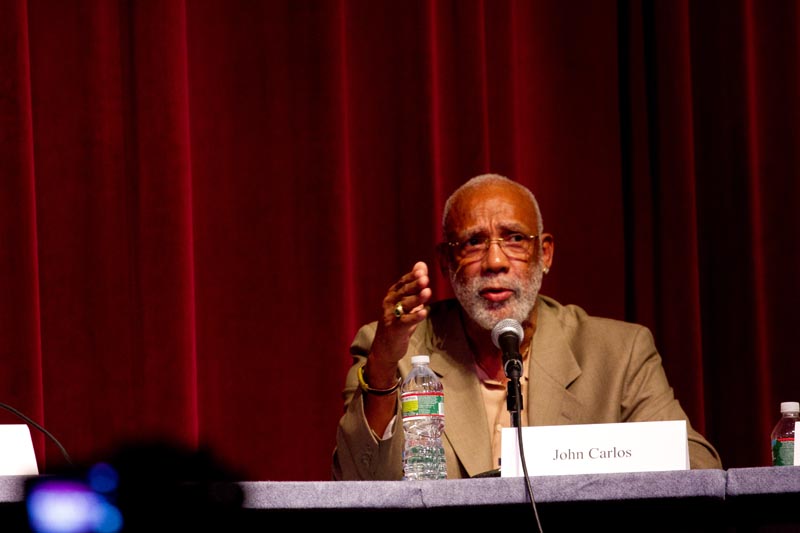

They joined several others in two afternoon panels to discuss the state of sports. Among them were Dr. John Carlos and Dr. Harry Edwards, who were involved in a historic protest effort in 1968. Mr. Edwards, a sociology professor and social activist, urged blacks to boycott the Olympics in Mexico City that year. Instead, Mr. Carlos and Tommie Smith, took to the victory stand after the 200 metres, raising their black-gloved fists for human rights and going shoeless (with black socks) in support of the world’s poor.

Mr. Carlos often held the audience in his thrall with stories about his aspirations and tribulations. He grew up wanting to become an Olympic swimmer (“I was the best bathtub swimmer in Harlem”), but abandoned that dream when his father rubbed his own black skin and told him it wasn’t possible. He turned to track, he said, when a police officer finally caught up to him and told him he had a talent for running.

In his boyhood, he had tried out the fisted salute after an event, and was promptly booed, he said. Fifteen years later, he did it again in Mexico City, but by then it was on a global stage.

“God hooked me up, all the way up to the victory stand,” Mr. Carlos said. “The first thing I said when I got off the victory stand was, the shackles have broken away from John Carlos . . .” The rest of his statement was drowned out by the crowd’s applause.

Mr. Edwards ticked off a list of daunting problems for black athletes today, and in society as a whole, warning of a “collapse of the black infrastructure in sports in America.” He cited the high incarceration and murder rates among black males, as well as the lack of job opportunities.

He and others cautioned that children on the playground need to know the long odds of prevailing in sports, and sometimes the high social costs for those that do. Historically, blacks have been given opportunities in sports purely for financial reasons, not out of a sense of egalitarianism, said Mr. Edwards.

“These are business arrangements,” he said. “They have nothing to do with brotherhood.”

“In terms of sports, not only must we teach our children to dream with their eyes open, we must learn to dream with our eyes open, to understand the full scope of what we’re involved in,” he added.

William C. Rhoden, New York Times sports columnist and author, put it another way earlier in the session.

“The dream is fine,” said Mr. Rhoden, author of Forty Million Dollar Slave: The Rise, Fall and Redemption of the Black Athlete. “But you’ve got to prepare for plan B and plan C.” That means getting an education, Mr. Rhoden and others suggested.

“You will always be able to do what you want to do as long as you have the education,” said Ms. Tyus.

Panelists spoke about the thin ranks of blacks in the upper echelon of the sports industry, whether in management and ownership positions of teams or even key executive positions in media that cover sports. Even in the ranks of players, including pro basketball, where foreign-born players have made inroads, and in baseball, where African Americans now make up only eight per cent of players in the majors.

“When we think of sports as a tool of economic empowerment, we have a long ways to go,” said Dr. Jocelyn Benson, a professor at Wayne State University law school. Wharton Business School professor Kenneth Shropshire went so far as to suggest that America’s emphasis on sports is grossly misplaced.

“I think it’s important to put it out there that the focus on sports for us is not what we should be doing,” he said. “Not only should it not be a plan A, it probably shouldn’t be B or C.”

At one point during the afternoon, Mr. Ogletree lamented: “I don’t hear a whole lot of good coming out of sports. What is the answer?”

Like it or not, sports often reflects society and its problems, some panelists said. “I think the issue is not to get out, but to get better at what we are involved in,” said Mr. Edwards. “And this is what I meant when I said we have to teach our children how to dream with their eyes open, to be aware of what is happening.”

Richard Michelson, an author, said he draws on sports stories to inspire children, turning to Mr. Carlos, who was sitting to his left on the stage.

“That’s why I’m writing about sports, because kids are drawn to sports. This man, when he raised his fist, he put his career on the line. He had a higher purpose.”

The athletes spoke of the dedication and discipline they needed to succeed. And Mr. Carlos spoke of sports as his platform, which afforded him access to Adam Clayton Powell Jr., Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

It also meant sacrifice and the courage of one’s convictions, he said, and not being afraid of “offending our oppressors.” The 1968 protest got him tossed from the games and incurred the wrath of many white Americans.

Ms. Tyus, who won gold medals in the 1964 and 1968 Olympics, explained her own philosophy:

“Life is a struggle,” she said, “but I always think I’m bigger than the struggle.”

Comments

Comment policy »