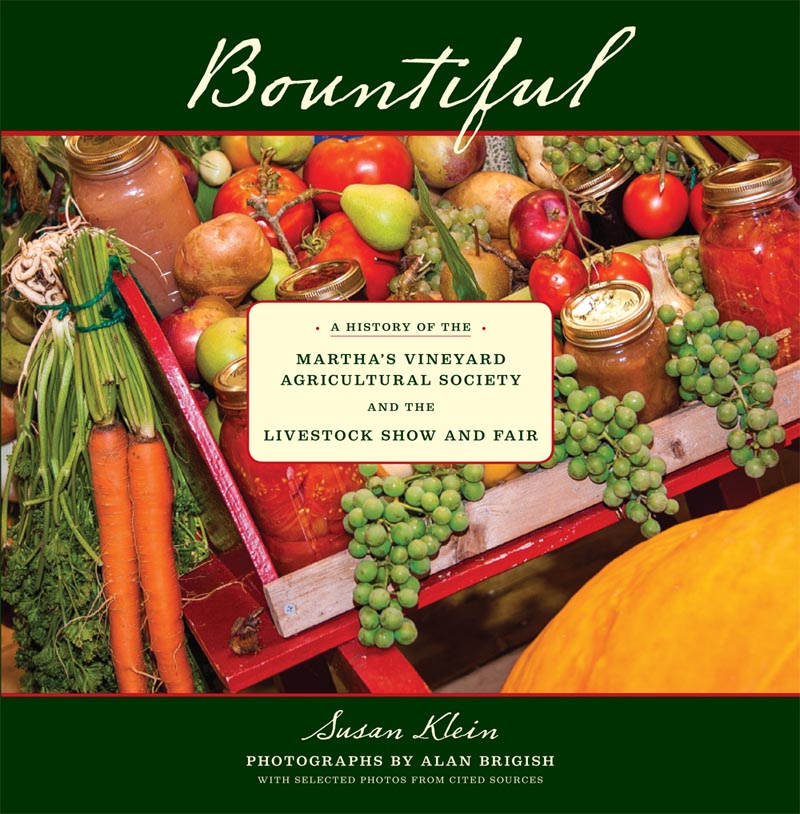

Excerpted from Bountiful: A History of the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society and the Livestock Show and Fair, by Susan Klein, with photographs by Alan Brigish (Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society, 2012).

This excerpt is taken from chapter 9 which tells the story of the midway and how it came to play an integral part of the annual Island tradition.

“My favorite was the Scrambler! It was really fun!”

— Dylan Biggs, 7 years of age

Desiring to showcase only the workings of the farm and “the mechanical arts,” and to partake in neighborly competition, those most influential in the workings of the Society kept the Fair strictly agricultural for almost a hundred years. As carnival attractions did not boast a sparkling reputation in that early era, the Society shunned all suggestions that they be included.

After visiting the Vineyard Fair in 1911, State Board of Agriculture inspector N. B. Turner noted in his report that attendance was small, the weather bad, and “the absence of Midway attractions makes a difference... It was an agricultural fair, pure and simple, with no trotting, no fakirs and no games of chance, in short it was the cleanest fair I ever attended.”

During World War II, times were challenging on many levels. After the war, those who worked so diligently to revitalize the Fair followed through with the 1942 plan to schedule the event in August to welcome summer guests, and, as John Alley put it, “within a couple of years, they would entice some carnival — something different — to come along.”

In 1951, according to Mr. John MacKenty, “it was Mrs. [Virgeen] Walton’s imagination and vision as to what the fair needed to give it renewed life and make it more attractive to the public which brought to the fair the Ferris wheel and the Flying Horses.” This changed the face of the Fair forever. Newspaper correspondent, Peter D. Bunzel wrote about “the real carnival atmosphere” and the joy of the children possibly having their first chance to take a “high circular loop in the sky” (for 20¢) or ride on wooden horses that “prance up and down” as well as go round and round.

The rides and the few concessions required a significant upgrade in electrical capacity — as was discovered when electricity overload plunged the Fair into darkness. Most took it in stride; a few asked for their money back.

On its last day, the Fair was scheduled to close at 5 p.m. Thanks to the record-breaking attendance, this was extended until 10 p.m., so that everyone who wanted could ride the Ferris wheel and merry-go-round.

In 1952, the Kiddy Whip, which carried riders in “cars” at the end of chains, was added: centrifugal force provided the source of delight. Colbert’s Fiesta was engaged in the early 1950s to provide rides, games and several food concessions. Soon after, they brought an aerialist — “something different.”

Many people recall “the man who climbed the pole.” The platform and pole were positioned 100 feet above the east fence of the Fairgrounds. Tim Maley recalled that the first year all the rides and music came to a halt, and then the Saber Dance was blasted over the PA system as The Great Lamar ascended. George Athearn said, “He climbed up twice a day, he’d do tricks on the way up. The owner of the carnival was the announcer — tried to sensationalize it a bit.” The man then performed on the platform. Everyone remembered what happened next: “And then he’d slide down a wire.” An undated clipping from the Standard Times identifies Colbert’s aerialists as “The Wizards of the Air” and adds that their “act closed with a sensational slide for life.”

Others recall a daredevil who climbed up high and jumped into a small pool of water — encircled by flames. Nancy Morris said, “I fell in love with the high diver. He was beautiful and exciting!”

Each year more rides were added until by the late ‘50s a full-blown and very popular midway was thriving. West Tisbury resident Johnny Athearn, who lived across the street from the Fairgrounds, talked about being a “carny” guy for a day: “As kids, we’d race to get the jobs to help set up. We got to eat in the cook tent with the carny folks. Our mothers would have had a fit if they knew we had a hot dog and a cup of coffee or something like that for breakfast. The real carnival people slept on blankets on the ground under the trucks.”

Johnny’s older brother, George, agreed: “We’d hover around waiting for them to come. It was a big deal.”

Current Society president Dale McClure recalled that local kids would get hired to break down the rides at the end of the Fair. They could each make $5 a ride if they helped; this could add up to $40 for a night’s work. “That was man’s pay, then!” Dale said.

During the 1960s, neither the Fair nor the Society was at its strongest. The carnival experience in 1971 had been unsatisfactory: portions of rides reportedly had been left at other fairgrounds, and the carousel arrived without its music.

Two things changed the following year. Alice Matthewson, veteran booster of “all things Fair,” returned as Fair manager in 1972, and Larry and Marian Cushing took over the midway, promising “a family operation.” Reduced rates for children’s rides and a cooperative spirit marked the beginning of a long relationship between the Fair and the Cushings. In The Grapevine of August 16, 1972, there appeared a nearly half-page ad from the Cushings thanking the people of the Island for the invitation and “the Steamship Authority for their co-operation in bringing the equipment to the Island.” Mrs. Cushing runs the business now, and Larry Cushing, Jr., who represents the fourth generation of this carnival family, works for his mom. They’ve been operating the carnival at the Island Fair for four decades.

Round and Round

The Ferris wheel lies on its blue bed, spokes and buckets folded up like a carpenter’s rule. The hydraulics droning underneath push the collapsed wheel upright. With a team of four ready to work, the fellow in charge gives the OK. The Ferris wheel unfolds one spoke at a time, mirroring the merry-go-round gear in the perpendicular. Once expanded and muscled into place, each is secured with an assortment of keys, rings, and wedges from the toolbox built into the rig. Each spoke is pinned and checked, and checked again, the same sequence repeated for each segment. Up pops a bucket seat, then another spoke. With each pie slice of air and armature, the great wheel gets ready to provide “the best seat in the house.”

Each ride manager runs his or her own ride. But everyone helps each other as needed with assembly and breakdown. They hail from far and wide, and a friendlier crew would be difficult to find.

Jesse, who assembles and runs one of the rides, said, “Folks are real polite here. We left some tickets on the ground to see how long it would take for them to get picked up.” Nodding in amazement, he continued: “Three days. Yes — it took three days.”

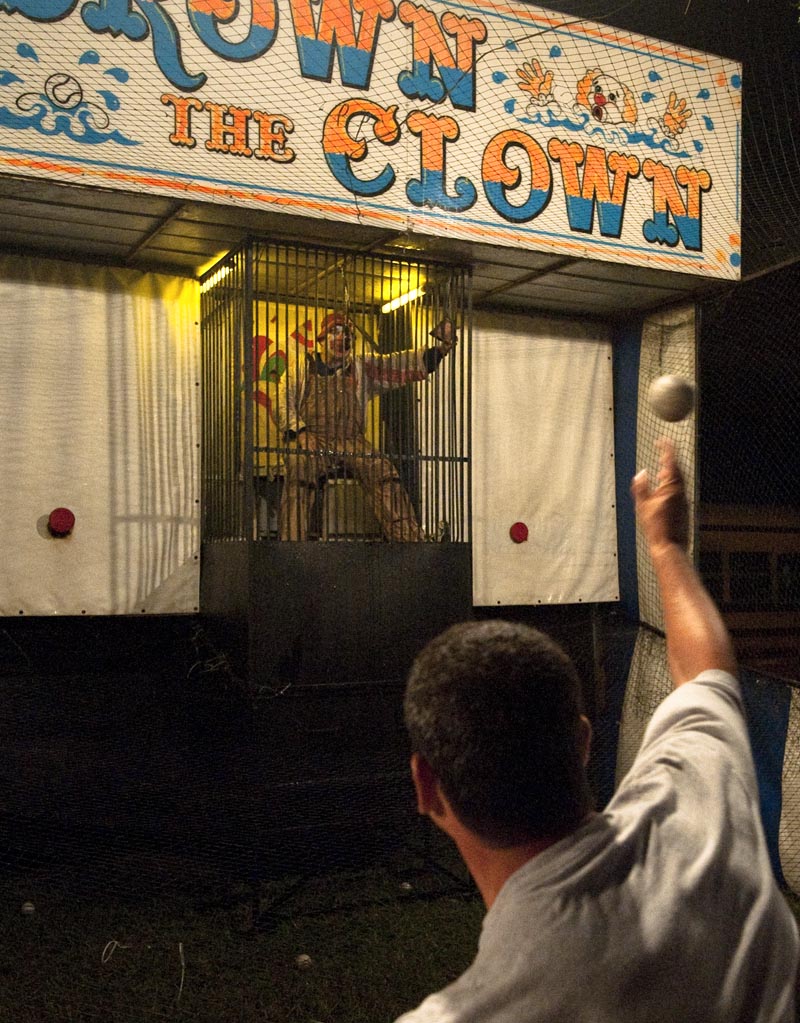

Dennis, who manages one of the games of chance, said he’s played many different kinds of communities, indicating a huge economic continuum. The people at the Island Fair “have been really nice and that made my job really nice, too.”

During August 2011, the Obama family was vacationing on the Island, and the girls came to the 150th Fair. The president’s younger daughter, Sasha, said Dennis, “started paying out in change. It was hilarious to me. Her dad had said during the campaign, ‘There will be change.’”

The flashing lights and Day-Glo colors, the bass drone of generators pulsing under the honky-tonk music, the shriek-accompanied swooping and spinning, the summer night air; the smell of corn dogs, fried dough, popcorn, and French fries sweep around the Fair with a tantalizing allure. The children laugh and scream and beg for “one more ride, ple-e-e-e-e-ase!” A new ride or game of chance may be added now and then, but the Cushings have kept their promise for four decades: it’s still a “family affair.”

The midway may not have been in the original trustees’ vision. But it is indeed a substantial part of the contemporary tradition, offering once-a-year delights. Since 1977, the Cushing family has made generous annual donations to the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society’s scholarship fund. Asked if that’s a tradition in every town they work, Larry Cushing, Jr., said, “No. But this is a special place.”

About three decades or so ago, the Ferris wheel was absent for several years, perhaps because it was considered passé. When it returned, it seemed right at home in front of the old Hall — as so it does today on the green in front of the new Hall. Like our Agricultural Fair itself, the Ferris wheel symbolizes a simpler time, an age to which we may not really wish to return, but from which we seem eager to distill a less complicated sensibility — and to hold it close.

Comments

Comment policy »