I received the omen in the Catskill Mountains. It was made manifest on a postcard that arrived at summer camp. A little plastic lobster was chained to the corner: Dear Shelley, We’re having a wonderful time in Martha’s Vineyard. You would love it here. Next summer, we’ll bring you. Words to that effect. Why were my parents in a vineyard? Who is Martha? Long after those questions were answered, I wondered how the lobster survived the postal system all the way to upstate New York.

Mom and Dad made good on their promise, and lo, this August marks my semi-centennial of footfall on Vineyard soil. Visions of my Oak Bluffs summers of youth have blurred around the edges — surely because of lapsed time, versus addled brain — but these things I know:

The trip from New York was a seven-hour slog. Six toll plazas interrupted the stretch of the Connecticut Turnpike, and every last one of them turned cruising speed to molasses and tried even the patience of grownups. But we kept our eyes on the prize. Mom was giddy at the sight of any car with bikes on its tail. They must be headed to Martha’s Vineyard! She would declare this as far from the Vineyard as New Haven.

In Providence, the route abandoned us to meandering secondary roads through small towns and peculiar rotaries all the way to Woods Hole. Fascinating after a fashion, but . . . we had a boat to catch. We boarded this boat, the Naushon or Uncatena, and summer after summer, never, ever did we remember to brace for the steam whistle that bounced us from our deck seats like the dupes we were. No matter. We sucked in the salt air to the very depths of our lungs and anticipated the first fried clam from the first greasy carton from Giordano’s. Some things don’t change. Thus far.

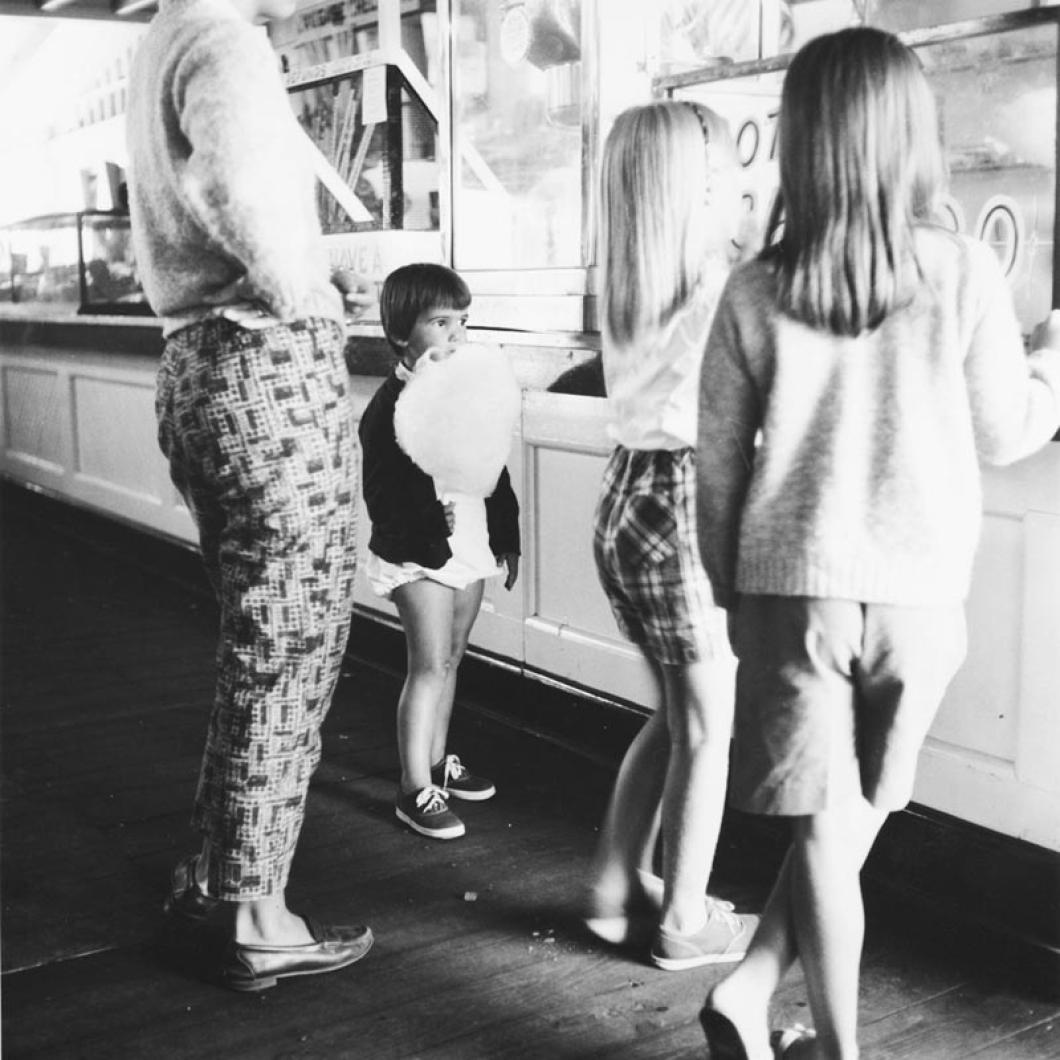

All ferries arrived in Vineyard Haven, but being in an Oak Bluffs state of mind, we never felt we had quite arrived until we crested New York avenue and beheld the dazzling crescent of Oak Bluffs harbor below. Honk if you remember the magical view that vanished with the embattled building of the bathhouse now smack in its way. My parents rented me a bike, first thing, and said go forth. My agenda wasn’t crammed with tennis lessons, sailing lessons, farming camps, riding camps and whatnot. No appointments had to be made or minded. We children of summer invented our days, bare-footing the beaches, the parks, the streets. I was going to ride one of the paddle boats on Sunset Lake one of those days, one of those years. I assumed they’d always be there. Rainy day? No problem. Picture puzzles, Scrabble, jacks and comics occupied the hours, in lieu of iPads and X Boxes. When the walls of the house could no longer contain young energy, we took off in rain slickers to movies at the Strand, to Hilliard’s for a chocolaty cube of heavenly hash, to the bowling alley, where human teenagers ran out to reset our pins, to Old Variety to poke through narrow aisles of souvenirs (maybe that’s where my plastic lobster came from!) or to the Flying Horses. To this day, I brag to little children that I could grab four rings from the carousel at one go. It helped to be 12 years old and long of arm. No 12-year-old would stoop to be seen at the Flying Horses today. Hurricane coming? Bring it on! Nothing was quite so exhilarating as the sting of wind in our faces and the breaking foam at our feet, until someone in loco parentis scolded us fools off the jetty.

Grownups hardly needed to drive us anywhere. Residential subdivisions in the middle of nowhere were merely a notion back then. Darned near anywhere worth going — town, beach, pond or the home of a friend — was within a walk, bike ride or hitchhike from wherever you stayed.

My family stayed in old-school rental homes back then. Sheets and dishes were mismatched. Sometimes there was a television, featuring three snowy channels and feckless rabbit ears. Someone’s bedroom may have been the common highway to the bathroom. The landlord didn’t care that we brought the dog. When the roof leaked, we just grabbed a lobster pot. The power came and went. Once, a skunk came and went — through the house. We didn’t whine to the rental agent. In fact, there was no rental agent. Was there a telephone? Not even the grownups cared to check on things back home. They had discarded all concern for their workaday worlds on the far side of the Bourne Bridge. If we wanted to talk to someone on-Island, we called on them, knocking on screen doors and walking in unbidden. Who among us knew how to handle a phone without a dial anyway? Kids whose families owned their own homes seemed to stay all summer back then. Arriving in mid-August, I had to catch up fast with the social scene. I was supremely envious of the camaraderie of the cliques.

Grownups were about as un-programmed as young folk, aside from their tee times at Mink Meadows, where they fussed about mosquitoes yet never tired of going back. The tennis players among them simply showed up at the town court and cheerfully wiled away the wait time chatting with friends and showing off their tennis whites. Later, they might gather again at a “five to seven” — someone’s come-as-you-are cocktail party — straight from the court, the green, the boat or the sand.

Family time included certain rites of vacation that took us far afield of Oak Bluffs. On our annual excursion to the cliffs, civilization vanished just beyond downtown Vineyard Haven, and we rode for what seemed like hours through forests and fields barely despoiled by humans, save the stripe of asphalt beneath us and the shock of the clearing where the Up-Island Grocery stood. At land’s end, we clambered to the precipice just beyond the lone souvenir lean-to and scampered down the crevices of rock and clay. We coated arms and legs in the rich colors of Moshup’s pallete and watched them swirl away in the surf. We were clueless that we were strip-mining what we loved. The road home held the promise of a stop at the Vineyard Food Shop, maybe for a pie for dinner and a cookie for right now. Mom’s idea of a treat was a fluffy biscuit straight from the oven, which Mr. Humphrey proudly schmeared with soft butter. Other routine road trips took us across the barren flatlands of Katama to the roar of South Beach. Cleaned up and nicely dressed, we went to dinner in Menemsha, where I learned (the hard way) not to tap the ink of a lobster, and suffered the spooky ride back to Oak Bluffs in utter darkness.

But then it was house party time! Once I was a full-blown adolescent, that is. Back in America, it would have been: Where is this party? Who’s giving it? Do we know them? Your father will drop you off and pick you up. On the Vineyard, it was: Be home by 11. Bye! They assumed correctly, more or less, that the party house was within a two-block radius. They could not track us down on smartphones. If they had to fetch us, which they never did, all they needed to do was to listen for the bass notes of a booming record player and the vibration of young hooves on old pine.

If we didn’t know where the party was, we hung out on Circuit avenue with our confederates until we found out. We might have kept an eye out for the cute member of the opposite sex we’d spied that afternoon at our spot on State Beach (at the curve, before the big bridge). We might have whispered about whose car was seen parked off Barnes Road late one night and who was in it. There was no Post Office Square back in the day to catch the overflow of our restless swarm.

Summer’s big party-filled climax was Labor Day weekend, now an occasion of relative calm. But by the departure of the last ferry on Monday night, the season was out like the snuffing of a candle.

Nowadays, Circuit avenue of a summer’s eve is still awash in adolescents. Why do they just stand around? Oh. Right. But other things in a summer kid’s life have indeed changed over these fast 50 years. Many of those changes are actually good: Bike paths are good. Transit buses are good. The forces for conservation that keep us off the cliffs and otherwise protect our fragile treasures are good. The Oak Bluffs fireworks are good. But the bathhouse that blotted out the harbor view can go. And the paddle boats can come back. Who’s with me?

Shelley Christiansen is a writer, public radio commentator, real estate broker and year-round resident of Oak Bluffs.

Comments

Comment policy »