THE SMITHS OF POHOGANUT (excerpts of the early nineteenth century diaries of Hannah Smith and Rebecca Smith). Introduction and notes by Marian Ragan Halperin. Martha’s Vineyard Museum, Edgartown, 2013. 315 pages, paperback. $19.95.

If we want written accounts of Island life before the Gazette began to publish in 1846, we must usually rely on letters, town records, deeds, wills and diaries, many kept at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, some at the newspaper office, others at the county courthouse.

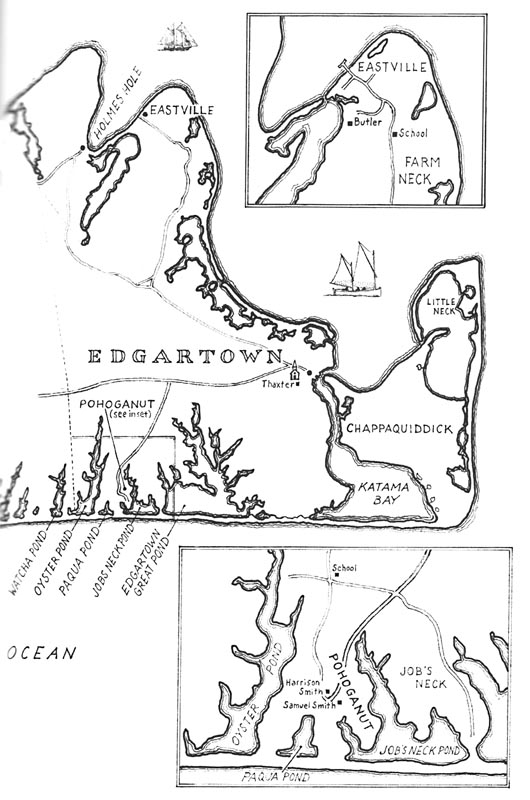

But understanding these documents can be a challenge, and not just because the handwriting often looks as flowery and untraceable as a vine crawling along a fence. Without context — meaning introductions, footnotes and companion essays — old journals in particular sometimes read like bulletins from another word, tantalizing but inscrutable. Going through them, we keep bumping over questions like: Who was this Reverend Thaxter the author keeps bringing up? Where was Holms’s Hole? Why would anyone think that eating a cucumber was tantamount to suicide?

In this vein, before you start in on the entries themselves, be sure to page all the way through the newly published journals kept by two young sisters who were living on the western frontier of Edgartown in the first quarter of the 19th century. Reading the attendant essays first and familiarizing yourself in a general way with the footnotes will make the this newly released collection of diaries called The Smiths of Pohoganut — published by the Martha’s Vineyard Museum and introduced and annotated by Marion Ragan Halperin, a former director there — that much more dramatic and engaging.

For those searching for glimpses of how things looked and felt on Martha’s Vineyard way back when — before resorthood, before even the vaguest hints of industrialization, even before the start of whaling as a serious Island enterprise — working your way through these sisterly journals can be a delightful and sometimes exciting experience.

The diaries of Hannah and Rebecca Smith begin in 1813, meaning that the two young women see British warships off the south shore and actually hear cannonading on the Atlantic. They write of visitors coming to their frontier home who are frenzied by their recent conversions to the evangelical Methodist and Baptist faiths, which were just then beginning to overturn the puritanical religious order of Edgartown as well as the rest of the Vineyard. They give us lovely descriptions of the prairie shoreline under moonlight and during snowstorms and gales. They describe personal and grinding bouts of depression and sudden flights of reverie. And they hint at romantic scandals in the “city” of Edgartown — which in the case of Hannah sometimes, painfully, are rumored to involve her.

The Smith sisters were the daughters of Love Pease and Samuel Smith, both families descending from the earliest white settlers of the Island, with Samuel working as both a farmer and register of deeds at the outpost Smith homestead. They began writing the first pair of journals when Hannah was 24 and Rebecca 18. (Curiously, one sibling often copied the entry of the other almost word for word; it’s hard to imagine sisters who would allow such a thing today.) Both young women were educated, loved and composed poetry and wrote much more about the world around them — visitors, news from the mainland, trips to town and the fates of friends and family — than of duller domestic chores, which out in the countryside must have been what they spent of their time dealing with.

As editor of this new collection, Mrs. Halperin knew what she was doing. In 2008 — again with the museum — she gave us the Civil War journals and letters of Charles Macreading Vincent, a red-headed, sometimes sardonic Edgartown youth who took us all through the South as a private serving with Company D of the 40th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers. As with the Vincent book, Mrs. Halperin provides us with detailed, cogent footnotes (which add meaning to the entries) and Smith family records (which outline the surprising prosperity of a family living out on the south coastal hinterlands).

But what really counts are the essays Mrs. Halperin writes on the subjects that matter most to the two young women, and these you really should read before you start in on the diary entries.

It’s not just that they explain and enliven the journals; they amount to the three or four of the briefest and best primers you’ll find anywhere on how the Vineyard dealt with marauding warships during the War of 1812. How it set up and ran its schools at the start of the 19th century. How the exhortations of a band of circuit-riding evangelists would eventually overwhelm the sanctioned Congregational church of the Vineyard and inspire the establishment of the Camp Ground and latter-day vacationland of Oak Bluffs. And how some of the earliest Island land transactions would lead to the establishment of a well-known farm on the margins of the oldest Island town.

The first set of diaries, kept by both sisters, covers one year, 1813 to 1814. Following this there is a gap during which the younger sister, Rebecca, both marries and dies. Then, single and often still bereft, Hannah picks up her pen once again and writes another diary between 1823 and 1824, during which we discover that the surviving sister is, among other things, an estimable poet.

Working your way through the diaries of Hannah and Rebecca does take some effort. You’ll find yourself keeping one finger on the page you’re reading while another bookmarks the pages where the footnotes run and a third sets off the addendum where those invaluable essays begin. But take the time and trouble: A lost world of personal Vineyard history — fully reanimated — awaits, thanks once again to Marian Halperin and the indispensable records of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

Comments

Comment policy »