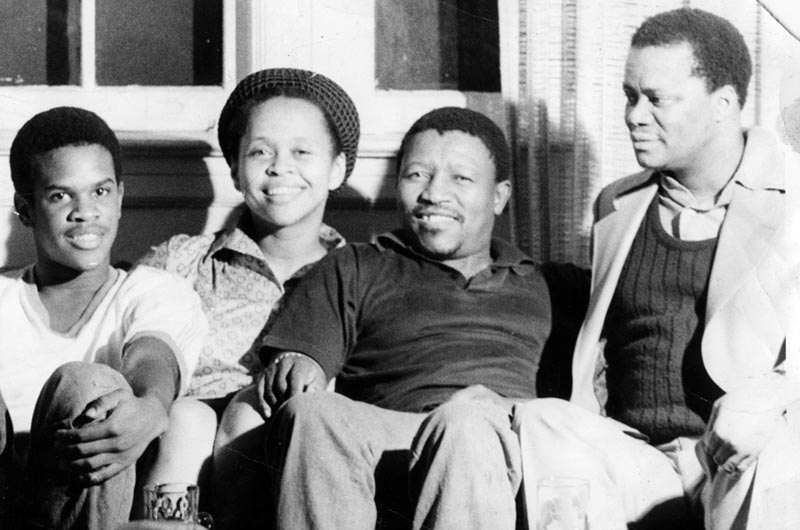

Benjamin Pule Leinaeng left South Africa in 1960 and entered voluntary exile. He was one of 12 freedom fighters who travelled throughout the world to raise awareness of the brutality of apartheid and to gather support for Nelson Mandela and the African liberation movement. He came to the United States as a television journalist, using media as a vehicle for liberation.

Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela, a 2005 documentary film by Thomas Allen Harris, Mr. Leinaeng’s stepson, will screen at the Oak Bluffs Public Library on Tuesday, August 19, at 1 p.m. and again at 3 p.m. The film will be presented by the Martha’s Vineyard branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. Mr. Harris will be a special guest.

The 12 freedom fighters were young men when they left South Africa, unaware that it would be almost 30 years before apartheid ended and they were allowed to return home. When they finally did return, most people didn’t know who they were or how they had contributed to their history. When Mr. Leinaeng died in 2000, Mr. Harris still knew only parts of the story.

In a telephone interview this week, Mr. Harris said he was a “rambunctious” child who would often fight with his father. But he also remembers the two of them spending time together and looking at his father’s photographs of his own childhood in South Africa. He said those images helped him visualize the experience of apartheid.

His stepfather’s funeral in South Africa was a major turning point. “I always just considered him my stepfather but in black South Africa there is no such thing as ‘step,’” he said. “I went there and realized that they were considering me his son, but in my heart that was the reality of the situation. He was the father that raised me. So it was kind of a big crisis for me emotionally and I found myself videotaping the entire funeral.”

In some ways, Mr. Harris sees himself as following in his father’s footsteps. “Many of the other guys chose the gun, but my dad chose the camera,” he said. Working as a journalist for the United Nations, Mr. Leinaeng helped to establish the ANC mission worldwide. “He wanted to use media to fight apartheid . . . He passed on that mission to me because I’ve used my camera to support liberation, freedom, and the idea that it’s absolutely critical to tell our stories.”

Two or three years into the making of the film, Mr. Harris was struggling with the script, when his mother, Rudean Leinaeng, one of the film’s producers, discovered a recording of an interview from the 1980s during which Mr. Leinaeng told his entire story. “It was an audio tape and I was able to use that interview to interweave his story and my story,” Mr. Harris said. “That’s kind of a theme in a lot of my work as a filmmaker and photographer.”

The film includes archival material — including some from Martha’s Vineyard, where the family often vacationed — and dramatic interpretations of South Africa in the 1950s. Most of the actors are South African. Some were professionals, but none had ever acted in front of a camera. To find them, Mr. Harris put out a call asking people about their engagement with history. The final cast spent time with the remaining disciples to get a sense of their experiences.

Bloemfontein, where much of the story takes place, and where many of the actors are from, has a thriving theatre scene. It is also the birthplace of the anti-apartheid movement and the ANC. As a highly conservative part of South Africa, much of it looks the same as it did in the 1950s, with unpaved roads and kerosene lighting. “So we really had an authentic backdrop against which we were shooting,” Mr. Harris said.

In the U.S., the anti-apartheid movement gained momentum in the 1980s, following the first decades of the civil rights movement. It was a global, multi-cultural effort. “We came together to bring down the apartheid system, and it was a struggle that took decades to do,” Mr. Harris said. “And I think most people who are of a certain age — certainly 40 and above — were part of that movement.”

But very few films have been made that portray the anti-apartheid movement from the perspective of the exile, he said. Mr. Harris receives emails from people around the world wanting to learn more about the 12 disciples, whose work helped shift the world’s awareness of apartheid. In 2006, the film was nominated for an Independent Spirit Award and was named best documentary at the Pan-African Film Festival in Los Angeles. It also aired on the PBS documentary series Point of View.

Twelve Disciples is Mr. Harris’s third film. His newest film, Through a Lens Darkly, which highlights black photographers and their relationship to their work, will screen at a private fundraiser for Williams College alumni in Oak Bluffs on August 22. Mr. Harris said his films form a quadrilogy, each one exploring the relationship between personal and public narrative. “They are personal films, but they are also films about larger historical movements,” he said.

Each film uses a variety of formats, including vintage Super 8-millimeter film, creating what Mr. Harris calls “a kind of meditation on a theme using collage.” In all of his work, he aims to help people recognize that there are many ways to see the same thing, and how the process of seeing shapes our identities: “Our identity is not just how people see us, but how we see the world.”

Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela will screen at the Oak Bluffs Public Library on August 19. There will be two showings, at 1 and 3 p.m.

Comments

Comment policy »