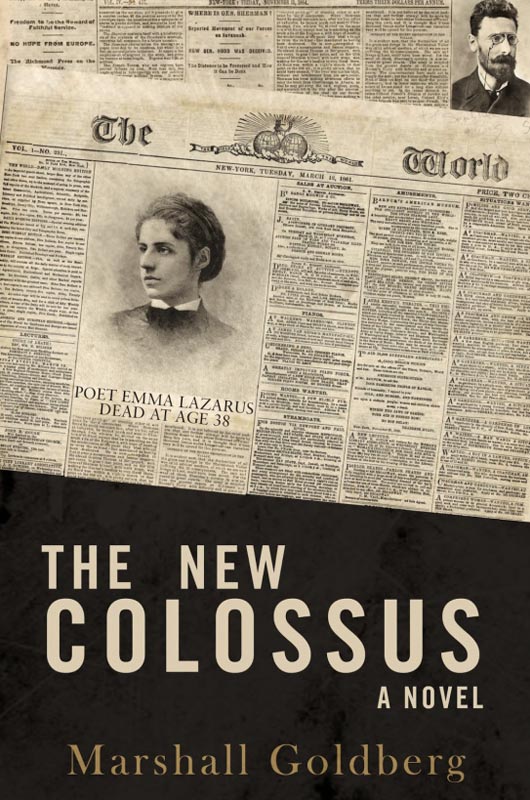

Marshall Goldberg’s masterful The New Colossus rivets the reader into 1888 New York and follows the beautiful and spunky reporter Nellie Bly, 24, through New York alleys, squalid insane asylums, sputum-slimed newspaper editing rooms and sinister corporate chambers to pursue the person(s) who murdered Emma Lazarus, author of “Give me your tired, your poor . . . ” — the immortal verses inscribed on the then newly dedicated Statue of Liberty.

If you ever wondered when Gotham got Gothic, this crackling, fast-paced historical fiction shows that Poe-like gloom and villainy are very much a part of the ethos and identity of late 19th century New York.

Gothic ironies abound in 1888 New York’s immigrant population, including the embarrassing case of the colossus, Miss Liberty herself. France’s generous gift to honor the Declaration of Independence and the Emancipation Proclamation, the 151-foot Frederic Bartholdi statue waited a full decade in France, broken up into 214 wooden packing crates, until New Yorkers got around to raising the $150,000 required for her 27,000-ton pedestal. The politicians of New York refused to allocate the funds, deeming it a waste of money, while the super rich of New York looked on with apathy and contempt. Yes, even the immigrant Liberty had trouble being accepted by the Americans.

Enter Joseph Pulitzer, who as a 17-year-old Hungarian Jew had served in the Union Army during the Civil War, long before he became a dominant force in newspaper publishing. Obsessed with Miss Liberty’s distress, the visionary Mr. Pulitzer took the issue to the people: he promised to print the name of every donor on the front page of his famous New York World. The crusade for Miss Liberty worked — the $150K for the pedestal was raised in a short period of time, all of it coming from 120,000 working class men, women and children. Liberty might never have emerged from her packing crates, but thanks to Mr. Pulitzer’s campaign, the last rivet of “Liberty Enlightening the World” was fitted in an august ceremony presided over by President Grover Cleveland on Oct. 18, 1888.

Mr. Pulitzer also obsessed on the mysterious death of the crusading poet Emma Lazarus, champion of immigrants and scion of one of America’s oldest and most respected Jewish families. He challenged the hard-nosed Nellie Bly to investigate, using any means possible. The police had been useless in the Lazarus case, and Nellie’s relentless quest for the truth quickly slams her up against some formidable and malevolent forces. It seems nobody wanted an uppity female reporter snooping around their real estate conspiracy, their planned railroad monopoly, their medical pathology laboratory, or even their sister’s radical literary legacy.

During her tireless and risky investigations, Nellie becomes romantically attached to Dr. Francis Ingram, a young (31) and highly principled physician, a veteran of the Indian wars, who collaborates with her on some forensic issues in the case and helps her tease out details of Emma Lazarus’s life in New York society. She is also aided by the feared theatre critic Alan Dale, who spirits her cause forward into encounters at the newly opened Metropolitan

Opera, notably with Charles Dekay, theatre critic for the New York Times and the immaculately tailored chief suspect in the Lazarus death investigation. “Charles Dekay was more striking than Nellie expected, dashingly handsome with an undeniable charisma that would overpower most women.” But Nellie Bly was a far cry from most women. Highly vulnerable yet intrepid and wily in a male-dominated world, she pioneered investigative reporting and laid bare schemes of corruption which rocked the city of New York to its core. Following her through this sinister gauntlet of personal challenges, adroitly rendered in an engulfing fictive sequence, the reader relishes the stark depiction of an unforgiving city — a city where greed, corruption and murder flourished, and where one brave woman and her allies teamed up in heroic and inspiring action to find the truth.

If you are looking for a bracing summer beach read that also fills you in on some disturbing details of New York city history, pick up a copy of The New Colossus. But with a warning: after reading the book, the Statue of Liberty may never again look quite the same to you, especially her promise: “I lift my lamp beside the golden door.”

Gerald Yukevich lives in Vineyard Haven.

Comments

Comment policy »