In 1997, the Island conservation groups published a sobering report.

Called Martha’s Vineyard: Choices for the Future, it warned that if current trends continued, the Island would reach a state of maximum development within eight years.

“Less than 10 years remain in which to plan and carry out steps to protect our most important remaining natural sites,” the 12-page report declared in part.

Now, 17 years later, this scenario of buildout, or full development under current zoning, has not yet been realized.

This year the Martha’s Vineyard Commission has come out with revised calculations that predict the Island won’t reach buildout until the year 2089.

The projections are illustrated in a new animation released this week that shows development over time since 1660. Commission cartographer Chris Seidel created the video, which is an update of a 2007 animation, using information from assessors’ databases and aerial imagery from the state Office of Geographic Information.

At the start of the 43-second video, the Island appears as a blank slate, rural and bare, but over time, scattered homes turn into cluttered neighborhoods until buildings spread coast to coast in all directions.

Red coloring begins in 2012, when the animation begins to illustrate projected buildout, with an average of 93 buildings going up each year until 2089.

The 1997 Choices for the Future report came near the end of a building boom on the Vineyard that had lasted for 30 years.

Since then the tools have changed for forecasting development, enhanced by technology. And development patterns themselves have also changed.

New data compiled by the MVC shows that peak building on the Vineyard took place between 1980 and 1989, when 4,560 buildings with a footprint of more than 400 square feet were built. The last decade of the 20th century also saw robust development, with 3,103 buildings constructed.

Then in the first decade of the new century development slowed considerably, commission data shows. A total of 2,238 buildings were constructed between 2000 and 2011. Projections for the coming decade assume that development will proceed at a rate similar to the early 2000s.

There are currently 19,205 buildings on the Vineyard, and the commission has calculated that as many as 7,273 more could be built in the future. (The model is complicated by an inability to show buildings that were built and later demolished.)

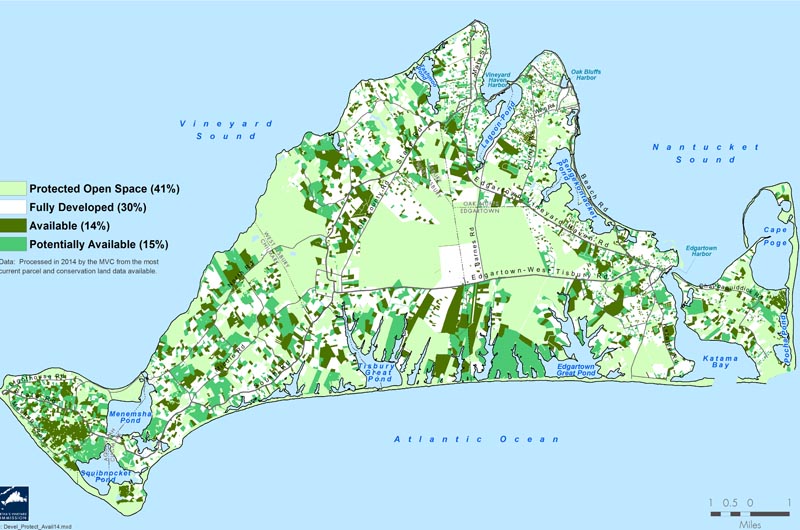

About 41 per cent of the Vineyard is now protected as conservation land and open space, while 30 per cent is developed and 30 per cent of the land is up for grabs.

“I think seeing an area with 40 per cent of protected land is excellent,” said Adam Moore, executive director of the Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation. “The numbers make me feel optimistic for the future.”

Broken down by acreage, the MVC uses four land classifications: protected open space, fully developed land, available land and potentially available land. At recent count, 17,107 acres of land are already developed and cannot be further subdivided, while 23,221 acres are considered protected lands, held under private and public ownership, including wetlands. That leaves 7,820 acres of vacant parcels available for development, and 8,892 acres that are already partially developed, but could be further subdivided under current zoning.

The Island has not reached buildout as predicted for many possible reasons: the cost of land on the Island has increased, and more recently the economic recession has taken a toll on construction nationwide, commission planners and conservation leaders said.

But the slower rate of development is also a reflection of the work the conservation groups have done to protect open space, said Leah Smith, who wrote the 1997 Choices for the Future report with Phil Henderson.

“The thing that is important to realize is that conservation groups have continued to be very active,” Ms. Smith said in an interview this week. “They have conserved substantial acreage. There has been real progress in preserving our beautiful landscape, and that is a very important thing to all of us who have lived here and all of us who visit the Island.”

Mr. Henderson said at the time, there was a sense that conservation wasn’t keeping pace with development. “This long-running trend of development looked like it was going to continue, and raising money and getting donations of land and money was not getting any easier,” he said.

The Choices report found that between 1971 and 1992, development on the Island surpassed the total land developed in the 330 years prior to 1971.

In retrospect, Mr. Henderson said the buildout prediction was somewhat overdone because it was based on recent numbers which were at a high point.

“You don’t know what the future is going to be,” he said. “All you have got to go on is recent history.”

Nevertheless, the report served as a wake-up call of sorts in the community, the authors said.

“I think at that point a lot of people began to think more seriously about it and it wasn’t just haphazard conversations here and there, but some of the decision makers on the Island started thinking, we have got to track this, we have got to monitor this,” Mr. Henderson said.

The report’s release coincided with the formation of the Conservation Partnership, a coalition of the conservation organizations that began to meet monthly to discuss land acquisitions.

“I think there was a lot of alarm in those days, because people were developing the Island to the maximum,” said Carol Magee, executive director of the Open Land Foundation, another conservation group that did limited development projects with open space as a component.

Even today’s projection of buildout is just that — an educated guess about future development on the Vineyard.

On one end of the spectrum, it’s an extreme prediction from a conservation perspective. It assumes that no further lands will be protected from now on, despite ongoing efforts by the conservation groups to continue to protect more of the Vineyard landscape. On the other end, if the economy were to see another boom period and zoning laws were relaxed, buildout could be reached even sooner.

“Some things will reduce this and some things could increase it,” said commission executive director Mark London.

And while development rates have decreased since the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s, land management practices have also changed.

“What we see is that there are fewer and fewer larger parcels available and from what I understand, more and more people are holding on to parcels 30 to 50 acres in size,” said Ms. Magee.

She said it used to be that development was considered the highest and best use of a particular parcel for appraisal and estate planning purposes. Instead, people are now holding on to large parcels of land instead of subdividing, and building larger houses on them, she said.

Mr. London also spoke to the trend. “Anecdotally, the nature of the development is changing a little bit from the 70s and 80s, when people would take a piece of land and develop it,” he said. “Now, there seem to be more people who are getting big pieces of land and keeping those big pieces of land.”

Despite the fact that it is heavily developed in many places, the Vineyard is still widely considered to be rural. But even in 1982, Islanders worried about whether the rural character of the Vineyard would soon be lost. A Gazette story that ran in May of that year warned that according to commission projections, in the 21st century housing construction on the Vineyard would be “riveted to rigid, evenly spaced grid plans, like another Levittown.”

Mr. London said he’s heard people lament that the Vineyard is no longer an open agricultural landscape, but he said if the Island suddenly lost its trees, the extent of development might surprise many people.

“If you got rid of the woods, you would see hundreds of houses across the hillside,” he said. “If you go to Google Earth and you look, the areas that are perceived as rural, they are perceived as rural but they actually have got a lot of houses.”

Some of the rural character has been preserved as a result of the Island roads district of critical planning concern, which regulates development alongside Vineyard roadways, Mr. London said.

“What the Vineyard is going to look like 20 years from now is largely what you see from the roads and from the water, and if you design it well, the Vineyard might not look so different from what it does today,” he said.

Mr. Henderson said there isn’t one tipping point at which the Island will lose its rural character. Instead he said the change is incremental, and involves day-to-day decisions that erode the character of the Vineyard, like the taller NStar poles installed last summer.

“I think it’s a process and it’s because there are so many things that contribute to it over so many years. It is very hard to see and to grasp,” he said.

Tools like the new commission animation and historic movies made available on the Gazette website tell the story of slow change on the Island, Mr. Henderson said.

If the resources had been available in 1997, he said an animation would have helped illustrate the Choices report.

“The more we can do of that, the better,” he said. “The MVC has come up with a spectacularly wonderful way to illustrate what had happened.”

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »