They say that creativity is intelligence having fun. Nowhere is that more true than in the cartoons of The New Yorker.

Bob Mankoff is the magazine’s cartoon editor. Each week he sifts through and evaluates thousands of cartoons, and the magazine buys about 15 of them. In other words, roughly 1.5 per cent of all submissions are accepted.

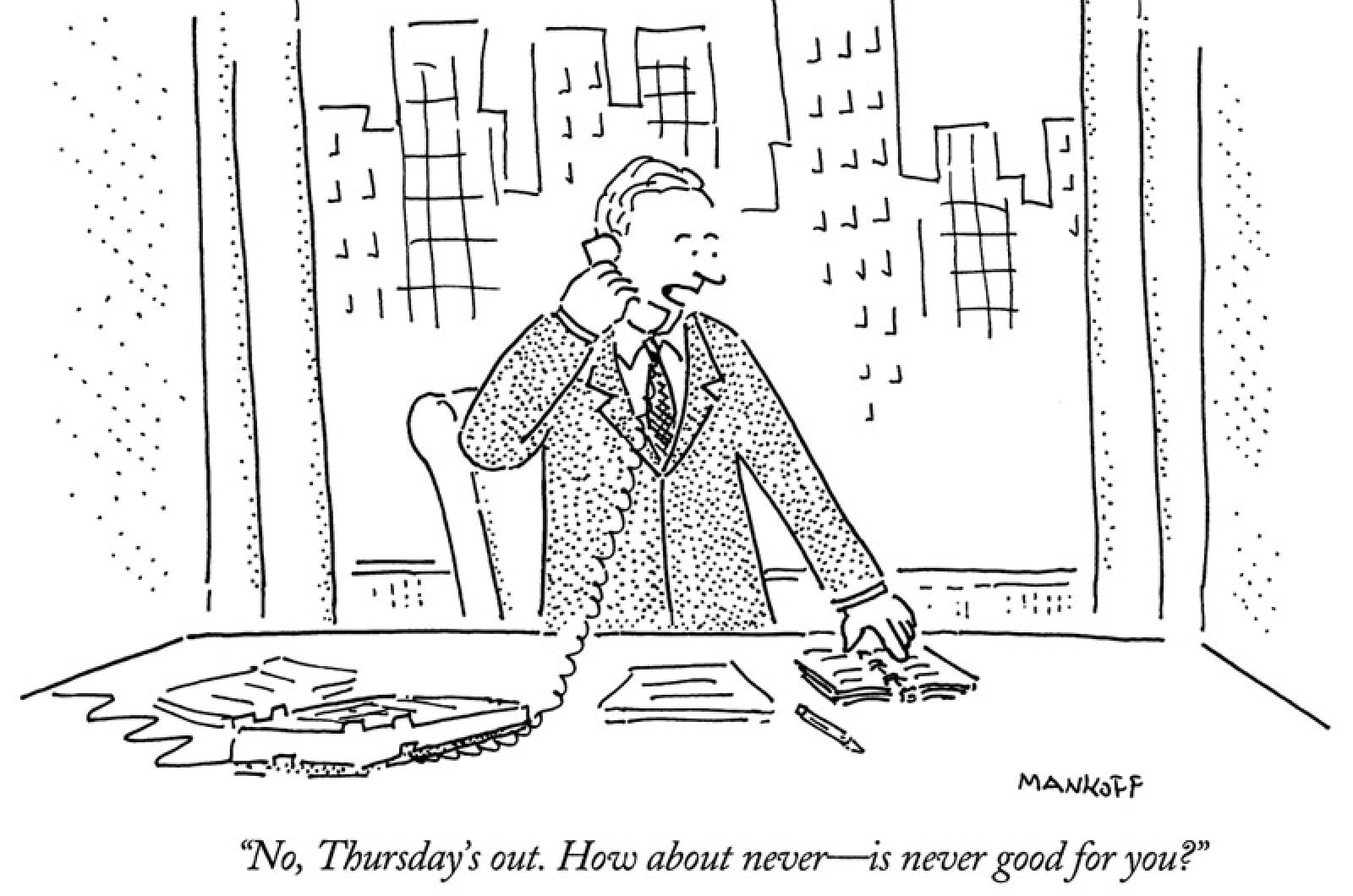

Mr. Mankoff is a cartoonist himself and the author of the 2014 memoir titled after his most famous cartoon — How About Never, Is Never Good For You? He is also the subject of Leah Wolchok’s new documentary, Very Semi-Serious which will screen Friday night, July 24, at 7:30 p.m. at the Performing Arts Center at the regional high school. Mr. Mankoff will take part in a discussion after the film, along with New Yorker cartoonists and Vineyard residents Paul Karasik and Mick Stevens.

The process for submitting cartoons to The New Yorker is the same for seasoned contributors who have sold upwards of a thousand cartoons to the magazine over the course of their careers, and new hopefuls. Every Tuesday they file into Mr. Mankoff’s office, one at a time, some nervous, others inured to the rejection tied to the routine, and spend a moment explaining their work to the editor.

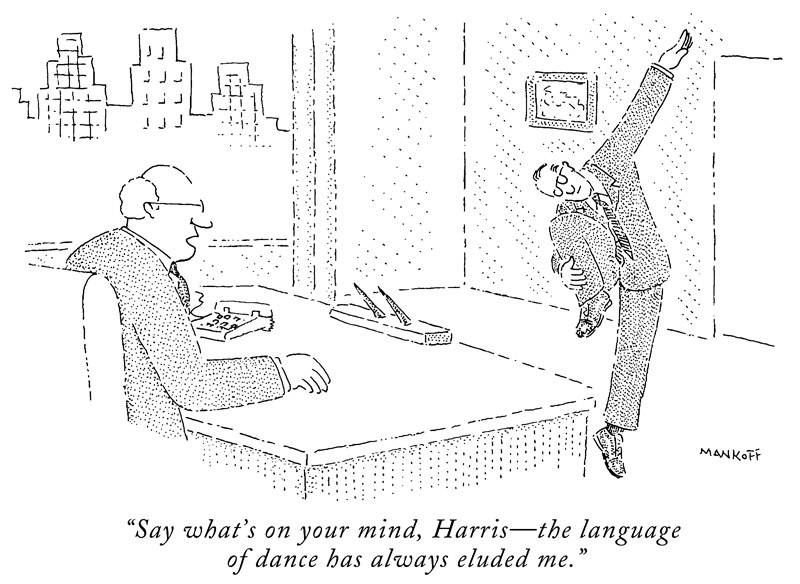

“I used to say I would go into the magazine for my weekly humiliation,” says well-known cartoonist Mort Gerberg. The best work, however, is that which does not need explaining.

“Cartoons should not feel like a struggle. They’ve got to work very, very quickly,” says Mr. Mankoff in the documentary film. Very Semi-Serious reveals that Mr. Mankoff is drawn to work that is immediate, visual and comic, as are readers of The New Yorker. But his taste is not narrowly defined by his own, single brand of humor.

“Sometimes the best tastes are acquired, and we look for the thing that doesn’t taste the sweetest right off the bat,” he said in a phone interview with the Gazette. “Sometimes I myself don’t think it’s funny but it may be intriguing, and maybe it’s something that will be funny on repeated exposure. So I look at cartoons and humor as eclectic and nuanced and interesting rather than this monotonic judgment that it’s funny.”

The New Yorker cartoons speak to a multi-generational audience, and so its cartoonists are, by design, an inter-generational bunch. Very Semi-Serious studies the backgrounds and motivations of the cartoonist as a breed of artist.

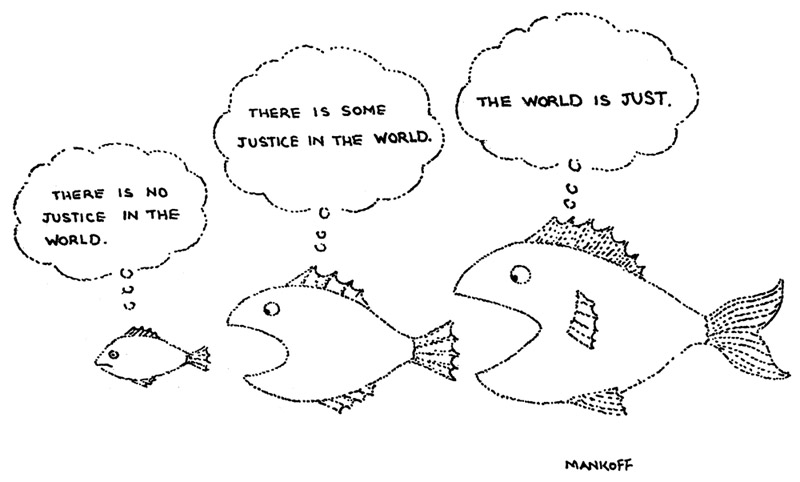

“In this particular group you do see some of the hurt of the humor — and the humor comes from getting a rise from things that don’t go well,” said Mr. Mankoff. “No cartoon is about good marriages or happy vacations. There is no humor in those things.”

Instead, New Yorker cartoons poke fun at and find humor in marital discord, office politics, parenthood, aging, death and more.

“It’s an exaggeration to say they are tortured, but one thing that is necessary is things must bother you in some way,” he said. “If you are completely content with the world it’s unlikely you are going to see it with a sharp, satiric or even ironic eye.”

Regular New Yorker contributor Emily Flake reflects in the film on how parenthood has changed the nature of her cartoons. “Some of the stuff I’ve submitted is exploring the darker side of motherhood say, more than, you know, as many dick jokes. I still submit dick jokes, but now they are baby dick jokes.”

One of her cartoons depicts a mother holding a toddler in one arm and a glass of red wine in her free hand. The caption reads: “It’s a magic potion that makes everything you say interesting.” Another cartoon shows a woman talking to a friend as she sends a young, uniformed child off to school. “It wasn’t our first choice of schools, but we had a Groupon for it, so what the hell,” the caption reads.

While most cartoons in the magazine tackle universal subject matter, some are inspired by street scenes of New York city. “Try honking again,” reads the caption on a picture of car passengers stuck in gridlock traffic.

When creating his own cartoons, Mr. Mankoff views humor as a way of sustaining life’s displeasures, and even tragedies. The New Yorker cartoon after which his memoir is titled shows a businessman speaking into a phone while looking at his datebook, saying: “No, Thursday’s out. How about never — is never good for you?”

In another drawing, a woman aims a gun at her husband who ducks behind a couch as he answers a telephone. “As a matter of fact, you did catch us at a bad time,” reads the caption.

Mr. Mankoff was hired to run the magazine’s cartoon department in 1997. He has been at its helm ever since.

“I don’t think I really did a good job when I was starting,” he admits in the film. “It was like a plane that was running on automatic pilot. But a year into it I realized this was a plane that was going to run out of fuel unless we intercede it.”

He decided to open up the cartoon submission process to allow for a greater range of voices and viewpoints to be represented. But he still faces the constant challenge of evolving the art form so that it remains a viable medium in the age of digital media and clickbait. He believes the key to cartoons’ lasting relevance and appeal lies in the generational diversity of The New Yorker’s contributors.

“The biggest kick for me is seeing this whole new bunch of people do it and at the same time we don’t put older cartoonists out on an ice floe to die,” he said.

The New Yorker also runs a popular caption contest each week on its back page. These cartoons are sourced from regular weekly submissions.

“Usually we pick one whose caption is not quite there, take it off and use that for the caption contest,” said Mr. Mankoff.

The judging process is inclusive and collaborative. A cartoon assistant scrolls through an average of 5,000 caption submissions, which are then whittled down to 60, from which Mr. Mankoff selects about eight to send out to The New Yorker’s staff via SurveyMonkey. Three finalists are selected based on staff ratings. The ultimate winner is chosen through a public, online poll.

Mr. Mankoff is optimistic about the future of cartoons and the ongoing evolution of The New Yorker’s brand of humor.

“Young people are creating their own things based on the template that is The New Yorker,” he said. “It changes like music changes. Every song you hear is based on some other song. It might not seem much different but if you look at a song today and go back 30 years it’s very different.”

He also opines on their easy to consume format, and suitability for our society’s diminished attention span.

“It’s an ideal form for the internet age. It’s quick, it’s consumable. You might not like it, but you are never going to get bored with it.”

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »