September 25 marks 50 years since In Cold Blood, by Truman Capote, burst into the American consciousness. The true crime tale of a brutal multiple murder in Kansas by two recently paroled felons was first published on this day in 1965 as a four-part serial in The New Yorker. A year later it was published as a book. It still makes “top 100” lists, it is still taught in schools, and it still serves as a first rate example of “literary journalism” for new generations of writers.

And for a week in 1960, Don Cullivan of Oak Bluffs was right in the middle of it all.

Linked by coincidence to Perry E. Smith, one of the killers, Mr. Cullivan sat at Mr. Smith’s side during much of the trial, and kept him company in his cell. He also found himself among a small group of observers that included Mr. Capote, who was already well known, Harper Lee, who was about to become a sensation as the author of To Kill a Mockingbird, and Richard Avedon, who went on to become a world renowned photographer.

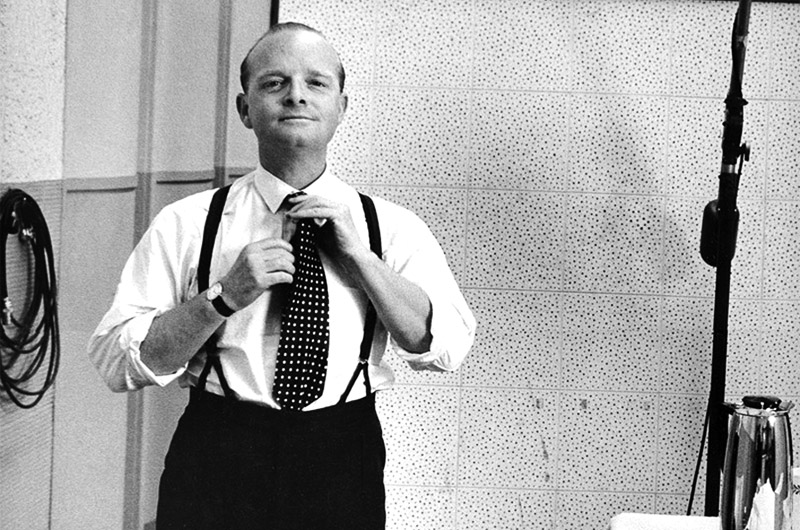

“Capote was Capote,” Mr. Cullivan said. “He’s just a walking circus.”

Sitting in his spacious Oak Bluffs home, most of which he built himself, Mr. Cullivan carefully thumbs through all the mementos he has saved over the years, including letters in Mr. Capote’s tiny, tight penmanship, and letters from Mr. Smith, including diagrams, poems and ruminations on his fate. Among the most interesting is a note Mr. Smith intended to drop to two strangers from his cell window, asking in big bold letters for them to get him a hacksaw blade. He never got the chance to drop the note, never got the hacksaw blade, but he sent the note to Mr. Cullivan.

Though long retired from an international career as an engineering consultant, Mr. Cullivan is fit enough to walk two miles each day. His memory is razor sharp, and his intelligent blue eyes light up when he remembers the circumstances that led him to cross paths with a despised murderer and a couple of literary giants.

He had just enlisted in the Army, and much to his dismay, found himself operating heavy equipment in the Philippines, instead of on the front lines in Korea.

“There was this fellow who just got back from Korea,” Mr. Cullivan recalls. “He and I had bunks together. It was Perry Smith. He was a really likeable guy, smiling, happy all the time.”

One day, years later, while browsing through Time magazine, he saw a short account of the crime. Local businessman Herb Clutter, his wife, and two children were murdered in their home. Mr. Smith and his accomplice had hatched a plan, based on information from a fellow inmate, who told them that Mr. Clutter kept a safe full of money in his home. They hoped to make a big score, and they didn’t plan to leave any witnesses. The plan went bad. There was no safe, and they left the home with only a small portable radio, a pair of binoculars and less than $50 in cash. But they did carry out the part of the plan to leave no witnesses.

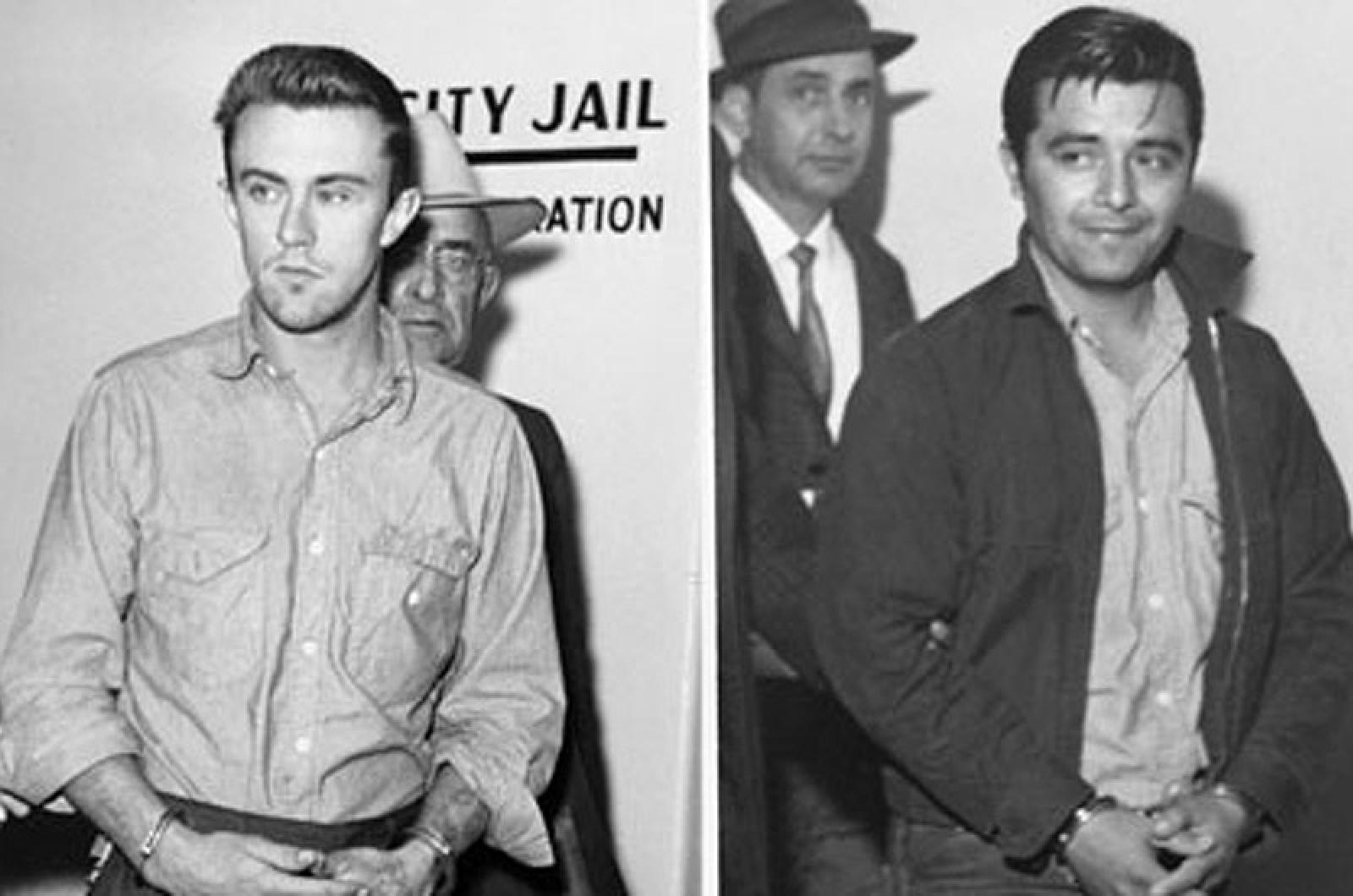

Accompanying the Time story were pictures of the accused, arrested in Las Vegas on Dec. 30, 1959.

“It was Perry Smith,” Mr. Cullivan said. “I wrote him a letter. My letter is verbatim in Capote’s book. It was kind of a preachy letter. I was going to save his soul. It was meant to be an act of Christian charity.”

To his surprise, Mr. Cullivan received a quick reply from Mr. Smith’s attorney, asking him if he could come out to Kansas to testify as a character witness. He agreed.

“It was all on my nickel,” Mr. Cullivan said. “Here I am a junior engineer, with two children and a third on the way, not making a hell of a lot of money. I felt it was a Christian obligation. We didn’t tell anybody in the family, or any friends.”

After a flight to Wichita, Kan. and an overnight bus ride to the courthouse in Garden City, Mr. Cullivan checked into a hotel and arrived at the courthouse a few hours later, where the trial was underway. Mr. Smith’s attorney was a gentleman lawyer who had very little experience in criminal law, let alone a multiple murder case.

“I don’t think he ever had a criminal case in his life before he was appointed by the court,” Mr. Cullivan said, speaking about Mr. Smith’s attorney. “It didn’t make any difference, frankly, because they both gave confessions.”

Mr. Smith’s lawyer wanted to establish his client as a real person, who might elicit some sympathy from the jury. He asked Mr. Cullivan to come to the front of the courtroom and sit beside Mr. Smith for the rest of the trial.

Mr. Cullivan also spent three long evenings locked in Mr. Smith’s cell, and those discussions became the basis for much of Mr. Capote’s account of the crime. He said he never had a twinge of fear, sitting inches away from a violent murderer.

“No, no, no, no,” Mr. Cullivan said. “We were Army buddies.”

Mr. Cullivan said some of his empathy came from knowing what a rough time Mr. Smith had growing up. He put himself in the killer’s shoes, and found some kindness.

“Where would I be, if I had a drunken mother who was a prostitute, and an overbearing father who was a tyrant, two brothers that committed suicide. Where would I be,” he said.

When not in the courtroom, or visiting Mr. Smith, Mr. Cullivan was hanging out with Mr. Capote and his group. He said Mr. Avedon was quiet, hardly saying a word. He described Ms. Lee as crude, and not a very pleasant person. But he and Mr. Capote hit it off the moment the writer walked up and introduced himself.

“It was like touching two wires together,” he said. Mr. Cullivan has written an interesting account of his experiences. In it he recounts an evening when Mr. Capote asked him to come to his hotel room, to discuss the narrative that would become In Cold Blood.

“Truman was alone, and bare-chested when I arrived,” Mr. Cullivan wrote. “Truman was 35 years old at that time and he was at the top of his game, both physically and mentally. He offered me caviar and vodka, which he had set out. He had a small refrigerator. The caviar was in a small silver bowl, and the vodka was iced.” There was some criticism of In Cold Blood, allegations that Mr. Capote took liberties with the facts, and invented scenes that didn’t happen. Mr. Cullivan disagrees.

At the trial, Mr. Cullivan’s character testimony was very brief. After answering a few questions on the witness stand, the prosecuting attorney jumped to his feet and thundered his objection.

“He was a vicious attorney,” Mr. Cullivan remembers. “This was his big case and by God, he was making the most of it. He practically screamed ‘immaterial, irrelevant, move that the witness be dismissed,’” Mr. Cullivan said.

The judge sustained the objection, and he stepped off the witness stand.

The jury convicted Mr. Smith and his accomplice after less than an hour of deliberation, and the two men were sentenced to death by hanging.

Mr. Smith continued to exchange letters with Mr. Cullivan following his conviction, when prison authorities would allow it. Mr. Cullivan wrote to him about his adventurous life, working in foreign countries, traveling to exotic places.

“I would tell Perry what I was doing,” Mr. Cullivan said. “He loved that. He loved adventures, he loved foreign treasures and treasure maps. He was not very in touch with reality, in many respects, that way.”

The last letter Mr. Cullivan wrote to Mr. Smith was returned undeliverable. Mr. Smith was executed in the early morning hours of April 14, 1965.

Comments (22)

Comments

Comment policy »