My wife Cathlin and I were married 14 years ago, on Oct. 6 in New York city, just a few weeks after 9/11. We were married in Judson Church, located on the south side of Washington Square Park, and as we took family photos in the park we could still smell the smoke from the fires of the World Trade Center.

For many months afterward we didn’t leave the city, not even to visit family in New Jersey. It was as if New York was wounded and to leave her for even a moment would be like abandoning a patient in need. But eventually, about a year later, we decided we needed a change. It wasn’t clear whether we were running away or toward something, we just knew we had to leave.

We came to Martha’s Vineyard in late September of 2002. Cathlin and I never had a honeymoon, we just went back to work, and so this in a way became our honeymoon — alone together on the Vineyard in the off-season. We found part-time jobs and I still remember weeping with happiness as I sat in the cab of a big front loader, scooping huge mounds of mulch into a pickup truck while blasting Bob Seger on a cool fall day.

We also took care of my grandmother, Ann Harding, who was dying.

My grandparents lived on Pennacook avenue in Oak Bluffs at the foot of Circuit avenue. Each summer my family traveled up from New Jersey to live with them. My mother was a teacher so she joined us for the whole summer, and my father came up on weekends, and on his two week vacation.

During the summer my grandfather taught us how to fish and kayak and play poker. Mostly it seemed his was a grand life, moving from one outdoor activity to the next, whereas Gram patrolled the house, cooking and cleaning and comforting our nightmares when necessary. She was a tough woman, with a deep disdain for dust and clutter, and if you ever mentioned you were bored, your next stop was sweeping the back stairs.

Our conversations sometimes ran something like this:

“Where are you going, Billy?”

“To the beach.”

“Have fun. Don’t drown.”

•

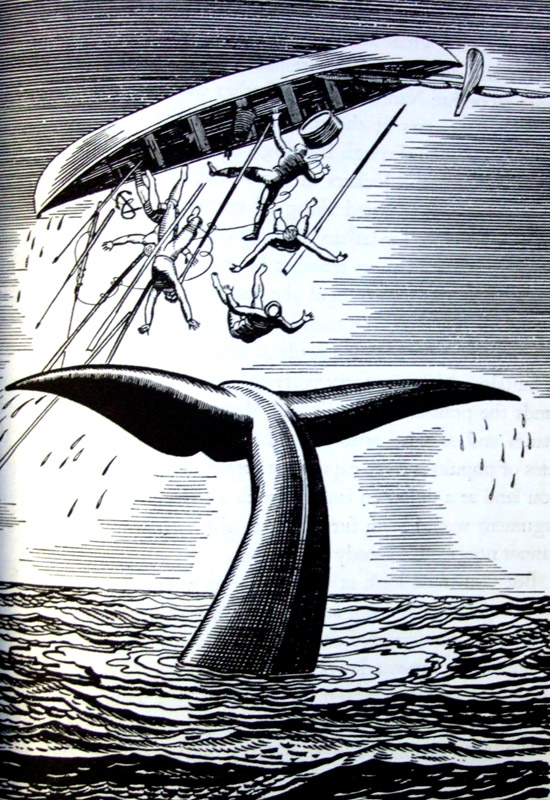

My grandfather, Bill Harding, came from a long line of Vineyarders, stretching back to the early 1700s. The Hardings were whalers, sailing out of here and New Bedford, and when the whaling industry faltered, they became shopkeepers on Circuit avenue. My grandparents met at college, set up on a blind date while Gram was at Moravian and Pop at Lehigh across the river. It didn’t take long for him to introduce his new bride to the Island. Gram once described that moment to me like this:

“Your grandfather brought me to this Island and there were all these Harding women staring at me, wondering who the heck this skinny girl was, and how she was going to do. Well, I outlived them all. That’s how I did.”

Gram was definitely proud of her status as the last one standing, but there was also a major downside to outliving everyone else, including my grandfather. She ended up in the house alone, even during the long quiet winters, as the rest of the family now lived in New Jersey and New York.

Earlier that spring, the doctors found a tumor in Gram’s stomach the size of a grapefruit. It would continue to grow the doctors said, but Gram decided she didn’t want an operation and that was that. She had been living alone for years and she was tired. The doctors didn’t know how much time she had, maybe a few months, maybe a year, and so Cathlin and I set up shop in a house owned by a friend just a few blocks away.

Our routines were quickly established. Each morning I would wake early and walk to Gram’s house where I would write in the old storeroom that used to be my bedroom as a child. Then, when Gram woke up, we would make coffee and toast and eat breakfast together, quietly starting our day. After the work day was done, we would all meet up again for dinner and some beer brought by growler from Offshore Ale. My grandfather had always said the stuff tasted like rust but we all loved it.

During the evening Cathlin and I would tell Gram about our days, sharing stories of traveling the Island, who we met and what happened at work. If I close my eyes I can still see the three of us sitting in the living room in sagging chairs, comfortable from years of use. The light outside is gray and there is a slight wind banging against the house. Gram’s chair is in the middle between Cathlin and me, and she turns from one of us to the other as we talk. I tell her about the four Nepalese guys who were just hired and are suffering terribly from the fall allergies they aren’t used to, and a trucker from off-Island who missed the last ferry and was shocked when I told him there were no strip clubs on the Island.

Gram also told us stories in return, opening up about her life in a way she never had before. She talked about growing up in Pennsylvania, about how poor she and my grandfather were when just starting out but how happy they were too. And one night she told us about the day her eldest daughter died at the age of 28.

“I cried so hard and so much that I exhausted all my tears and never cried again,” she said.

After cleaning up, Cathlin and I would head home. We didn’t have kids then or a television or cell phones and so we took long walks in the dark, listened to the radio and read. It would be many years before we would come back to the Island for good to raise a family, but already the way of life was mixing with my blood.

I found a copy of Moby Dick, a thick hardbound copy, and at night Cathlin and I took turns reading to each other from it, a few chapters each evening before we turned toward sleep. We taped these sessions too. Although we were young and still planning out our lives, with the business of death at hand each day we knew life was fleeting. The idea was that when one of us died we could be together again, our voices leading the way toward some island of solace while traveling aboard the Pequod with Ishmael and Ahab.

•

Gram died that spring, on April 8. Soon after, Cathlin and I packed up our Vineyard lives not knowing that we would return to the Island to raise two children of our own here. The tapes of us reading Moby Dick were tucked away in an old shoebox and I carried them with me to each new home over the years. When we moved back to the Island I placed them in the basement, high on the top of a bookshelf. I had never been moved to listen to them, they were a time capsule supposedly waiting to be unearthed only in the advent of tragedy.

But revisiting those days made me wonder what we sounded like back then, not really so long ago, and yet in some ways feeling so distant as to be lived by someone else. And so one dark night last week while the rest of the family slept, I pulled the shoebox down from its shelf. If this were a movie the lid on the box would have creaked and the tapes would have appeared dusty. But nothing was out of the ordinary, except I had to find a tape recorder, already a relic now, but something I use from time to time to do interviews. Then I pressed play.

At first the result was disappointing.

I don’t know what I was expecting but our voices did not sound very different. As we talked on the tape that first night about who would begin and where to place the recorder, the experience felt mundane. My voice sounded annoying too, and I almost turned the tape off immediately.

But I kept listening and then Cathlin took over the reading duties and as Ishmael searched for a ship and was surprised in bed by Queequeg, I remembered the first time I brought Cathlin to meet my grandparents and the Island on its own terms, in the off-season. It was a very cold weekend but on the first day we walked from Oak Bluffs to Edgartown, the wind blowing so hard we had to take shelter halfway behind a small dune.

I saw all that again, and then I saw Cathlin lying in bed a few years ago, weak from chemotherapy during her treatment for breast cancer. I saw our eight-year-old son reading to her from his favorite book and our four-year-old daughter lying in bed with her mother, buried deep under the covers and slowly caressing her ankles.

And then I was with Gram at her bedside, when she could no longer walk and floated in and out of consciousness. I was sitting beside her again, letting my fingers rub her face lightly like she used to do for me on summer nights when I could not sleep, and what my mother now does for my children.

All this I saw and more, so much more, as Ishmael led me out to sea just as my ancestors had once led him.

Comments (26)

Comments

Comment policy »