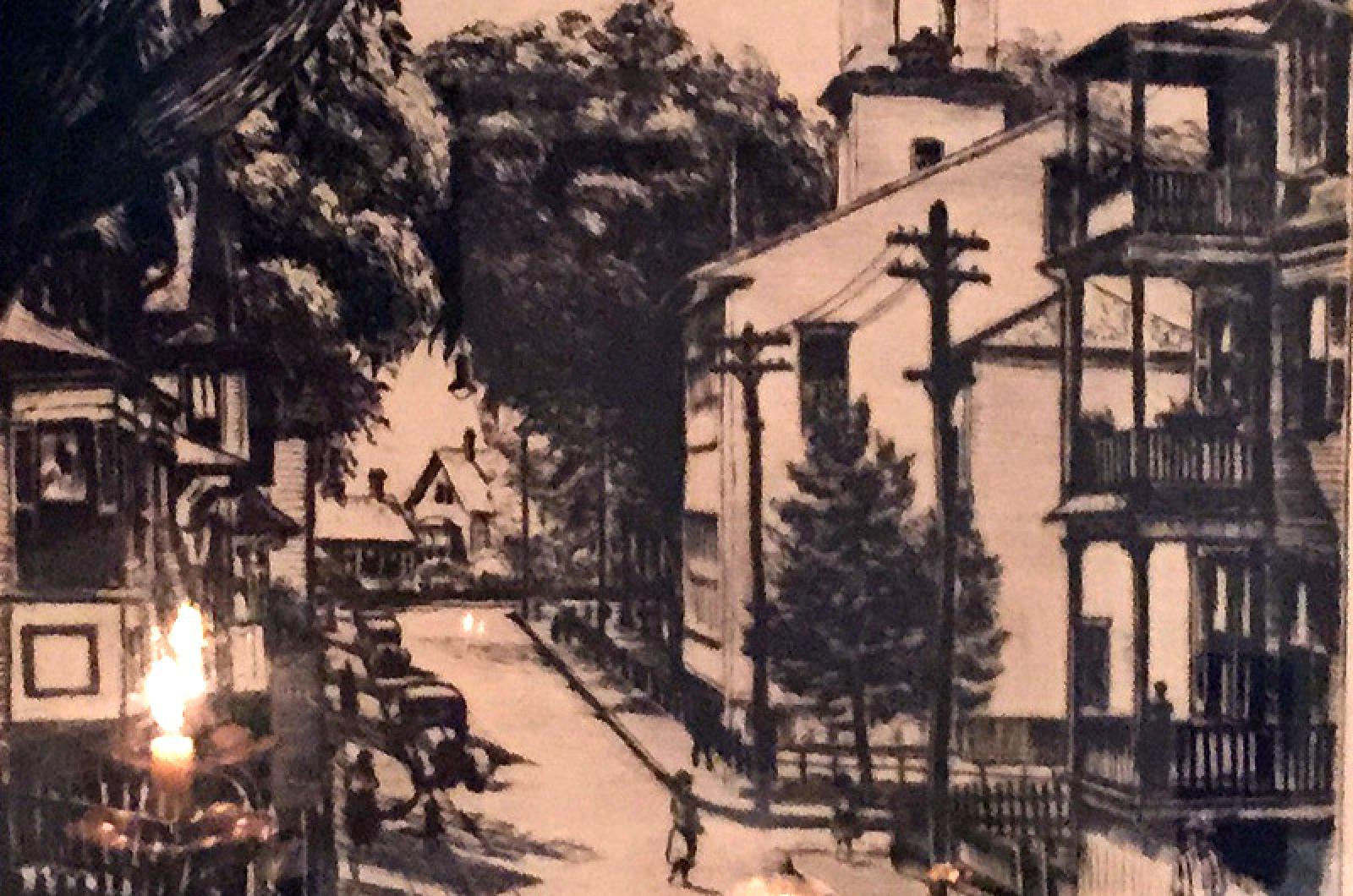

The protagonist of this story is a lithograph, acquired in 1966 in Greenwich Village, eventually landing in West Tisbury.

What must have been on the young man’s mind, a recent immigrant, to make him fall for the lithograph?

The year was 1966, the place Greenwich Village. Only a few shops stayed open late, even there. Late being 10 p.m. then. No sidewalk cafes or restaurants or fast food joints and certainly no alcohol served out of doors 49 years ago. This surely was not Montmartre.

But that’s relative.

Visiting headquarters from his Dallas outpost, the young man roamed delighted around this small bohemian section of New York that tried to live up to a song’s popular lyrics at the time, the town that never sleeps.

One bookshop with a gallery, five steps below sidewalk level, attracted his curiosity.

He met the owner. The owner spoke the immigrant’s native tongue, which was helpful since the immigrant’s English was rough. Turns out, the old man was an extraordinary chap. A longshoreman before the event of containers. A man who knew, worked and was immersed in life on the waterfront. A philosopher, an author, a mensch. He mesmerized the 26-year-old visiting from Texas.

From that quintessential port of entry to America, where waves of immigrants made landfall before him, the young man took the lithograph, along with a few published books from the shop’s proprietor, home to his bride of just about one year — to far away Dallas.

The lithograph has since traveled far. Not as far as the whaling captains whose oil helped build the New England steeple, the focal point of the lithograph. Still, it traveled far and frequently for a common lithograph.

From New York city to Dallas then back to New York city, it accompanied its owners. Resting there for one year, it spread calm on its admirers under glare-free glass in an avenue penthouse in Manhattan. That was the year one man took the big step for mankind on the silvery moon. From there it journeyed north to Toronto, Canada. And back to the United States a few years later.

At a home with a hearth in Bronxville, N.Y., it remained to inspire for another four years. After that it arrived at the shores of Long Island Sound, in New Rochelle, N.Y. Then a long, glamorless hiatus began, 35 years in duration. Relegated to the attic floor, to be seen by only visiting family and friends who possibly did not quite appreciate the New England solitude recorded there, it waited to be roused like Sleeping Beauty.

By the by it was.

Before cables were laid and fortunes lost by investors in shares of Atlantic Crossing and similar ventures, before satellites enabled earth-to-earth communication via the stratosphere, another first step had to be taken. That first step in commercial satellite telephony originated from the headquarters of AT&T to a house in Bronxville, N.Y. And there, in that house, in stark contrast to modern technology, the lithograph conjured up the past, telephone poles and all. There it awakened in its admirers the longing for a romanticized New England.

The pull was strong. It quickly enticed its owners to their first trip northward, to Cape Cod, where they imagined towns to look just like that. During their first extended weekend visit an indelible magnetic attraction was installed into the young couple, a longing for a past that was not ever lost, at least not for them.

Little could anyone imagine that an Atlantic crossing in the 21st century lay in the litho’s future, a journey to a former inland island in the former communist sea, to Berlin. There the lithograph just did not want to fit in, it did not feel at home. Little wonder. It would soon travel back to the New World home where it was created.

Securely packed into a clamshell Samsonite of past century vintage, it jetted west. The port of entry, befittingly, was New York (although JFK Airport, not the longshoremen’s seaport of lore that had received its present owner half a century before).

The last leg of the journey was an over-land affair. The lithograph traveled via Route I-95 and then by ferry to its present home in West Tisbury.

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »