Every so often Hollywood releases a movie that makes you ask: why did they ever make this? Not because of any ineptitude but because of its unfamiliar subject. Now we have Trumbo, starring Bryan (Breaking Bad) Cranston, a movie about a screenwriter who died nearly 40 years ago. A man with a sharp pen, a sharper tongue, one of the most highly paid script developers in the industry and someone virtually unknown outside the self-perpetuating lore of Hollywood.

They made this movie because it’s an unbelievable story about an unbelievable time in American history when the Bill of Rights was chopped and cut to fit a cause. And if we don’t know about this dark chapter we are doomed to repeat it. Dalton Trumbo received Best Story Oscars for two films in the 1950s — Roman Holiday and The Brave One. The point of Trumbo is that no one was supposed to know he hatched those ideas and he was also not allowed to accept the Oscars.

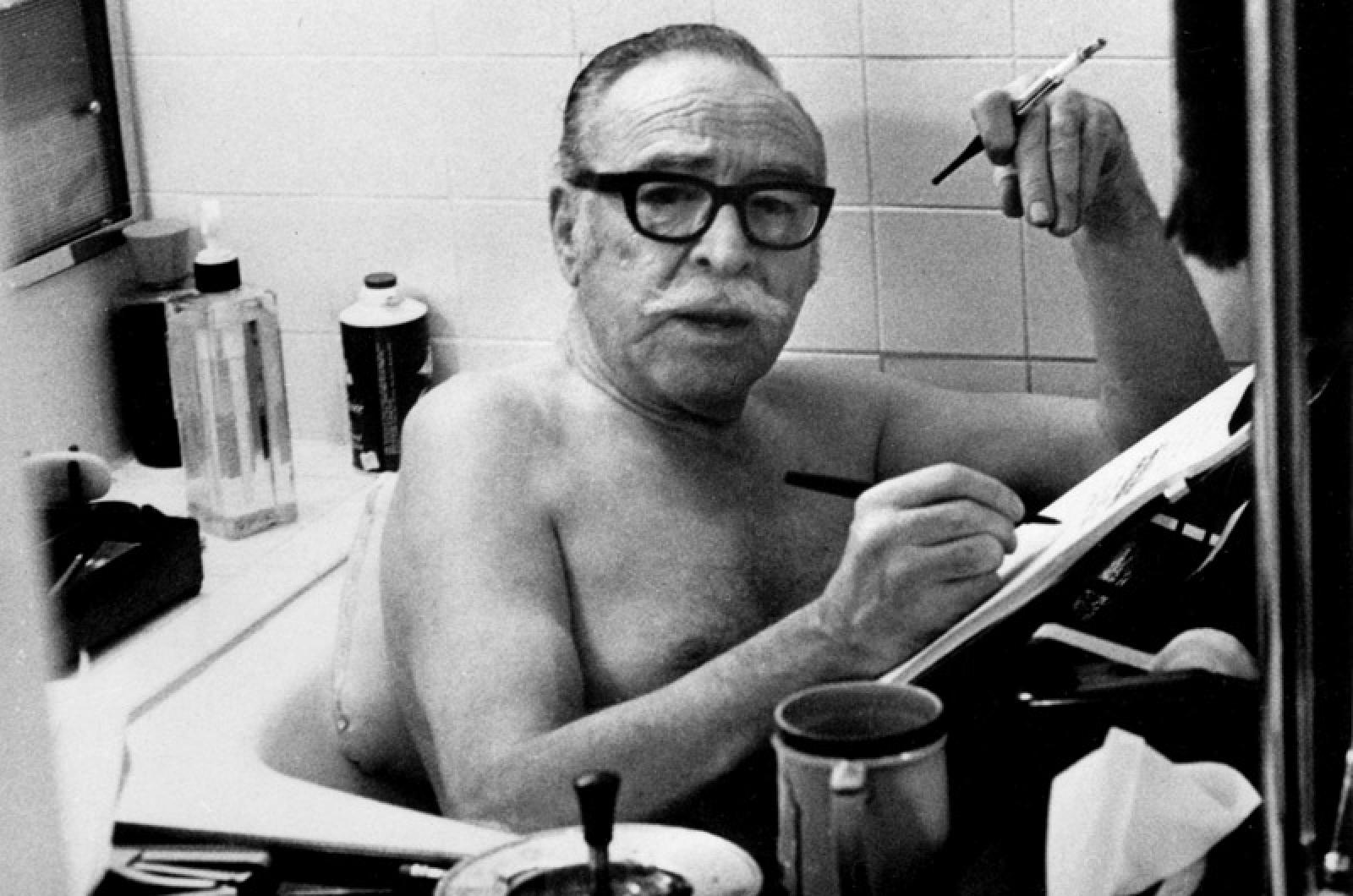

This is the story of politics run amok and the triumph of hypocrisy. It became the basis for Hollywood On Trial, the film I wrote 40 years ago, the documentary that featured the star of my previous column – Ronald Reagan. This film also featured an extensive interview with Dalton Trumbo. It was a pleasure to know him, no matter how brief.

When the House Committee on Un-American Activities in the grips of Cold War paranoia in 1947 came looking for the “Red Menace” in our movie industry, they came up against 10 witnesses who stood on their First Amendment rights and challenged the right of the committee to exist. These men became known as the Hollywood Ten. Cited for contempt of Congress, they all did prison time. One of them was Trumbo, within the group the most well-known and most acerbic. He told me he couldn’t complain about the charge against him for he indeed had contempt for that Congress “and for several since.”

Trumbo, like many others at that time, was criticized for being “prematurely anti-fascist.” This meant back in the 1930s he may have been a member of the Communist Party when that wasn’t illegal and may have supported Spanish Loyalists against Franco who was backed by Hitler when the U.S. chose not to get involved. Of course, by the end of the 1940s all that had changed. Now he was suspect. Now he was blacklisted. Hollywood let it be known that the man who wrote hits like Kitty Foyle, A Guy Named Joe, Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo and Our Vines Have Tender Grapes was unemployable.

But was he really? Trumbo understood Hollywood was a business and politics was just a game. So he employed “fronts” — writers who claimed to be doing his scripts and could be the faces at studio meetings. For 15 years there was a lot of winking going on, until hypocrisy tripped on the red carpet. At the 1957 Oscar telecast when Robert Rich was announced as the Best Story winner for The Brave One, the tale of a boy trying to keep his pet bull out of Mexico’s killing rings, producer Jesse Lasky Jr. accepted the statuette. Trumbo let it be known surreptitiously that he was Robert Rich and that quite possibly he had written other hits under other names. There was a collective gulp behind the scenes. Had the blacklist been whitewashed? Had everyone had enough of the charade?

It all came to a head in 1960 when Trumbo found himself hired under the table for Exodus and Spartacus. When I met with him, Trumbo joked how producer/director Otto Preminger, who had a reputation as a Teutonic taskmaster, worked with him on the Exodus script.

In my interview with him, Trumbo recounted his conversation with Preminger: “He said ‘some of these scenes don’t have your spark. And we must have your spark or I will tell everyone you wrote this.’ I told him if every scene were brilliant, no one would be able to sit through it. It’d be boring. He then said, ‘I will tell you what - make them all brilliant and I will direct unevenly.’ He then called me (Jan. 20, 1960) to tell me The New York Times had it on page one that he announced I was the writer for Exodus.”

Trumbo laughed. “I said then you must really hate the script.” Soon afterwards, producer-star Kirk Douglas told the world that Trumbo wrote Spartacus. Over the next two years the blacklist crumbled as duplicity exposed itself and lawsuits appeared.

Fumbling and stumbling, Hollywood studio bosses admitted that maybe some movies did get written by unemployable writers. But how were they to see past the pseudonyms and the fronts? A year before he died, Trumbo finally got the Oscar inscribed to Robert Rich. His widow received the one for Roman Holiday.

Hypocrisy was good business. CBS forced its number one star, Lucille Ball, to hold a press conference to say she had only joined the Communist Party to make her grandfather happy on his deathbed. She then quit the party. Obviously, CBS and the U.S. continued to love Lucy. And when successful playwright Arthur Miller answered his subpoena by showing up at the HUAC hearings with his new wife, Marilyn Monroe, on his arm, nobody was looking at him anymore. In short, in show business the color green meant more than the color red.

Trumbo screens on Saturday and Sunday at the Capawock Theatre.

Comments (6)

Comments

Comment policy »