Following a trend of looking for innovative sustainable ways to make a living from the ocean, the Island’s newest crop has been quietly planted in the water off Eastville Beach: two lines of Saccharina latissima sugar kelp, pioneer plants that could usher in a new Vineyard industry.

The Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group has been at work on the kelp project for about two years, with funding from the Edey Foundation. The native plant, which grows in large forests offshore, offers a great deal of promise, according to project leader Amandine Hall, as a sustainable, off-season industry that offers environmental benefits to boot.

“You don’t need a lot of water, there’s a basic set-up,” Ms. Hall said. “And people are starting to realize, if this can catch on, it’s good for the environment, it’s a great business to be in for a lot of people, and it could be great, healthy for humans.”

Lines of kelp were deployed last Thursday, one in 14 feet of water by the offshore Eastville oyster farm leased by Dan and Greg Martino and the other in deeper water down the shoreline, in an area supervised by the town of Oak Bluffs.

The shellfish group is following a process developed by Ocean Approved in Maine, one of the few commercial kelp operations currently in business. Following their lead, Ms. Hall has acquired the necessary permits and kelp know-how to test growing the crop on the Island.

Farming seaweed is similar in some ways to the thriving Island oyster farming industry; it is more sustainable and profitable than commercial fishing, some say, while cleaning the water. Kelp, like oysters, removes nitrogen and carbon from the water.

The market for kelp is out there, Ms. Hall said, particularly in the food industry. Kelp has been called the new kale, and tastes “like a big bite of the ocean,” Ms. Hall said. The nutrient-rich plant packed with omega-3 fatty acids is often used in seaweed salads, and there is a large market for it in Asia and Europe. Kelp is harvested in the winter but freezes well, Ms. Hall said, which could provide a consistent supply throughout the summer.

But there are a host of other uses beyond the plate, raising the prospect of kelp smoothies and spa treatments (seaweed wraps are increasingly popular). Kelp oil is good for skin and often used in high-end beauty products in France, she said.

Kelp can also be converted to biofuel and used as fertilizer. “I think people would be really interested in local fertilizer instead of importing it on the boat,” she said. “Kelp has a negative carbon footprint to grow. It’s super local, it absorbs carbon dioxide in the water, it produces oxygen . . . it’s kind of endless the advantages this crop has.”

And kelp could beget more kelp. “There used to be a lot of kelp around here and they have slowly disappeared, just like the eelgrass in our ponds,” Ms. Hall said. “But further away from our eyesight, in deeper waters so we don’t really see it as much.” Farming the plant could boost the species, she said, as kelp farms spore and increase biomass in the water.

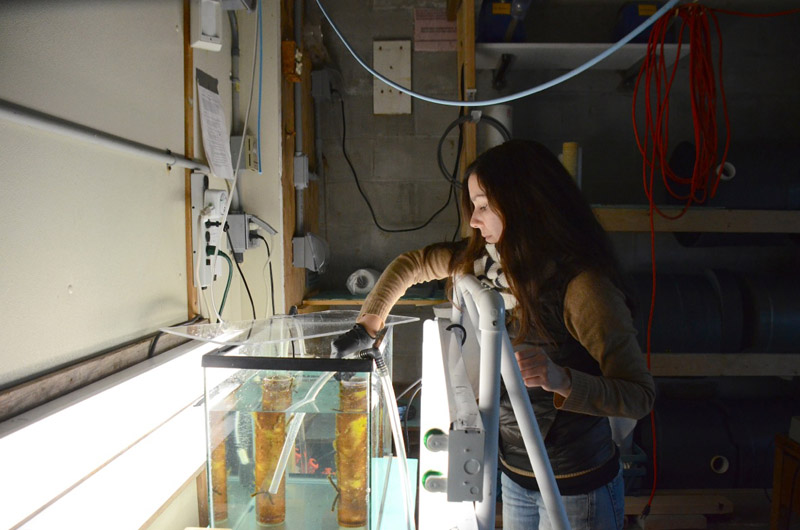

Growing the Island’s first kelp crop began with harvesting spores from a mature plant. The spores were nurtured on strings at the Oak Bluffs lobster hatchery. Once the plants were big enough, Ms. Hall waited for a cold snap to put them in the water; kelp is a winter crop.

The kelp was planted, so to speak, seven feet below the ocean surface, held in place with moorings. The thin string with the young, quarter-inch kelp plants is wrapped around a thicker rope. As the kelp grows they should take hold of the rope, Hall said.

Kelp is one of the fastest growing plants in the world, and if all goes well, the new crop will be ready for harvest in the winter or early spring, Ms. Hall said, before the water gets warmer.

The experimental phase will determine how well the kelp grows — Ms. Hall hopes it doesn’t detach from the ropes — and whether there is interest in the community about using this new product. The next steps would be finding interested farmers, looking for offshore sites in deeper water, and going through the permitting process.

The permitting is not yet in place for a commercial kelp farm, and there is not a seaweed industry in Massachusetts, Ms. Hall said. “It’s kind of a pioneer thing,” she said, adding that somebody has to be the first person to forge the path. There is already interest coming from oyster farmers, including Jeremy Scheffer, who runs an oyster farm on Katama Bay, and the Martino brothers .

Dan Martino said he is drawn to a 3-D farming concept, in which aquaculturists can use the entire water column. “You can grow more food in a smaller area than traditionally you could on a regular farm,” he said.

“Kelp’s just cool,” he added. “It tastes really good, it’s a seaweed, it’s a second crop we can grow in the wintertime, it helps clean the water . . . it’s cleaning up nitrogen, it’s cleaning up carbon. It’s something new and cool.”

Mr. Martino said the kelp submerged in the water by their oyster farm — visible only as buoys — is already growing, and could be a foot long in a few months.

“Having more than one product is a good thing,” he added. “If all of your carrots get destroyed, at least you have lettuce. If all your oysters get destroyed at least you have kelp.”

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »