Recently, the Gazette published an excellent article by my good friend and former Boston Globe colleague, Dick Lehr, concerning the release of two Hollywood films this year with direct links to the Globe, and to Dick himself. One is Black Mass, based on the book of that name, co-written by Dick and Gerard O’Neill while both were members of the Globe Spotlight Team. The second is Spotlight, now playing at theatres on the Vineyard, the highly regarded film that details the investigative newspaper work that uncovered the scandal involving the sexual abuse of children by members of the Catholic clergy.

Dick and I have several things in common: We both worked for the Globe. (I punched the clock there for 35 years before retiring in 1998.) We both are seasonal residents of the Vineyard. (My family has had property on Chappaquiddick since the early 1900s.) And we both have a connection to Spotlight, the Globe’s full-time, multi-member investigative team. I founded Spotlight and gave the team its name.

It was in August of 1970 that Tom Winship, the late, legendary editor of the Globe, approved my idea for a full-time investigative unit at the Globe. Spotlight was born.

Mr. Winship gave his approval with considerable apprehension — and I accepted it with equal apprehension. There were many who didn’t expect the Spotlight experiment to last more than a year, much less 45 years. Today it is the longest-running such unit in the country.

Here’s how it came about:

That period was the Golden Age of newspapers, when classified advertising was gushing revenue, no one knew the internet from a hairnet, and editors actually encouraged reporters to take sabbaticals to widen their horizons and improve their skills. At least Tom Winship did.

So in 1969, off I went — first for six months in South Africa to observe journalistic practices on newspapers in Johannesburg, Cape Town and Durban — and then to England to work on the London Sunday Times and try to learn “what makes it the best English-language paper in the world,” in Mr. Winship’s opinion.

Once there, it didn’t take me long to figure that out, or at least to identify one of the main pillars of that reputation. It was the existence of a full-time, multi-member group of investigative reporters known as Insight. It ran no bylines. No one outside the paper knew who worked on the Insight team. All the public knew was that whenever the Sunday Times published an Insight report, it went off like a bombshell. Insight revealed that Kim Philby, a high-ranking British intelligence officer, was a Soviet spy. Another Insight series revealed that a dancer named Christine Keeler, who also had Soviet connections, had seduced the British Secretary of State For War. A third blockbuster documented the birth defects resulting from Thalidomide, a popular new drug to prevent morning sickness in pregnant women.

I learned how the team was structured, the way it operated, some of its techniques. And when I returned to the Globe in the spring of 1970 at the end of my sabbatical, I told Tom Winship that we could do the same thing at the Globe. We could form the same kind of full-time investigative team — and have the same kind of success.

Tom heard me out, intrigued. But before he gave the proposition his stamp of approval, he wanted me to do one thing: try out the proposal on his pal Ben Bradlee, editor of the Washington Post, a newsman he greatly admired. “Let’s hear what Ben thinks of the idea before we decide,” he said.

So a few days later I flew down to Washington to meet with the Post’s distinguished executive editor. I was confident that my mission would be an easy sell. Mr. Bradlee would surely give the idea of an investigative team his full and immediate support, I thought. But I was in for a rude shock. I was only three sentences into my spiel, which I had carefully worked out in my head, when Ben raised his hand, palm out.

“Don’t do it!” he grunted in that gravely voice of his. “Big mistake. Tell Winship to forget it.”

Ironically, this was shortly before the Washington Post (and Ben Bradlee) would become world famous for the paper’s Watergate investigation by two young reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. However, a previous move by Bradlee to support investigative journalism at the paper had ended badly. Ben had assigned two big-name reporters to work in tandem, sniffing out investigative stories in the nation’s capital. Unfortunately, the experiment had been an abject failure. The veteran reporters had gone their separate ways, spending a lot of time and money with very little to show for it. According to Bradlee, the only result was a morale problem in the city room, where the cushy assignments were viewed with jealousy.

Now I had to go back to Boston and tell my boss that his friend Ben Bradlee hated the notion of a full-time investigative team, that the big idea I had brought back from my sabbatical year abroad would be “a complete disaster,” according to him.

It was an anxious time. Sitting in an antique rocking chair in front of Tom Winship’s desk, I nervously told him why I thought Ben was wrong, explaining that what we should do at the Globe — using Insight as a model — would be altogether different than what had been tried at the Post. There should be at least three reporters and a secretary researcher assigned to the team. The reporters should be young and eager, not jaded and know-it-all. The unit should have a recognizable name, giving it a bit of mystique and mystery. And above all, the reporters on the unit should work as a team, combining and coordinating all their efforts and information in the investigative articles that resulted.

Tom said very little while I was making these points, and when I finished there was a silence in the room that seemed to last an eternity. Finally he put his hands behind his head and leaned back in his chair. “Well, all right,” he said, peering at me through his thick glasses. “Go ahead. Let’s give it a try.”

I left his office a few minutes later and walked directly across the city room to ask the two young reporters I’d had in mind if they would join me in the endeavor. One of them was Gerry O’Neill, the Spotlight reporter who would go on several years later to co-author Black Mass with Dick Lehr.

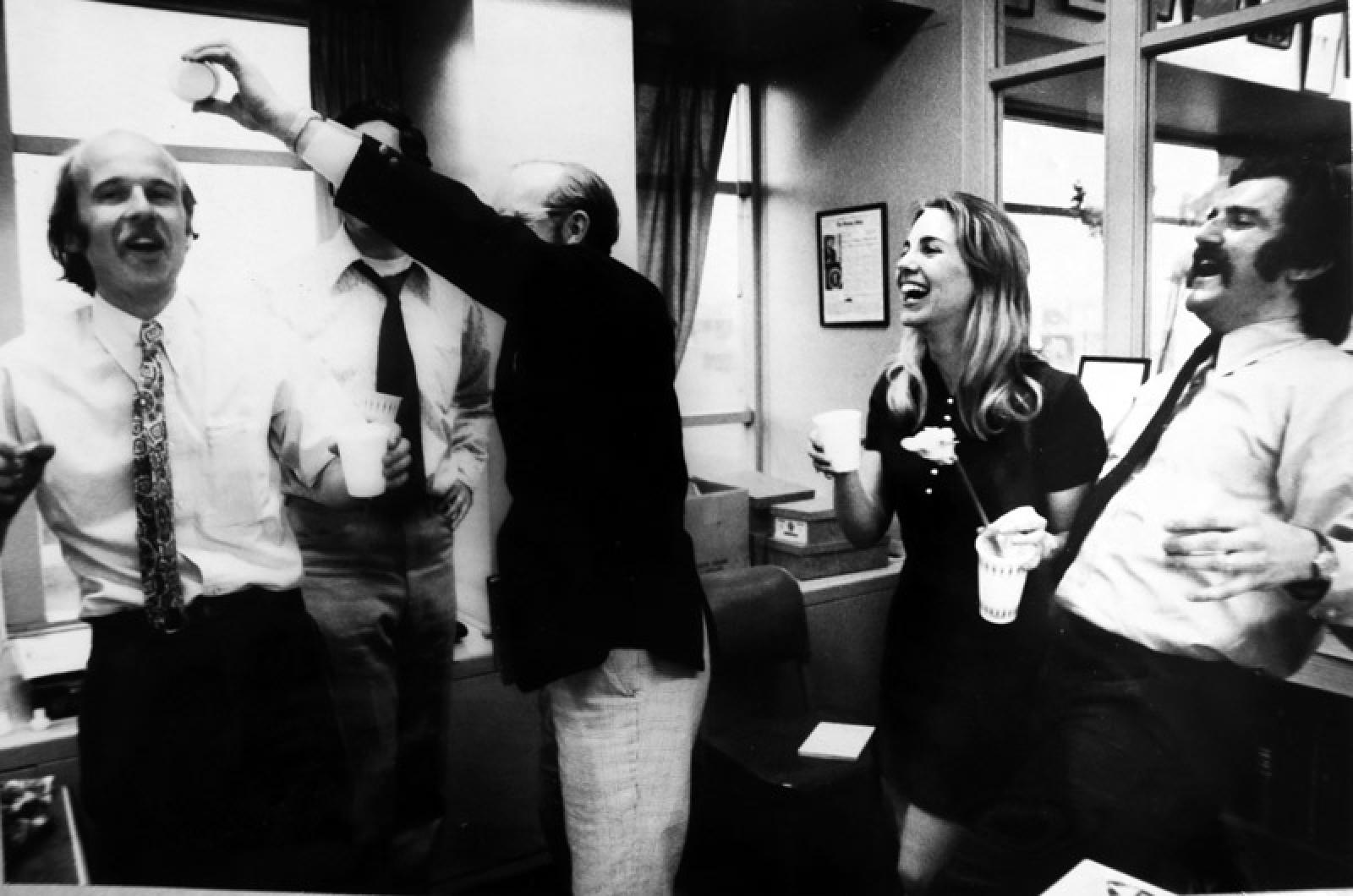

The Globe launched the Spotlight Team before the summer was out, and early the following year we published a series of investigative reports that detailed a vast network of municipal corruption in the neighboring city of Somerville.

One evening months later I was cooking dinner in my apartment when the telephone rang. It was Tom Winship. He didn’t bother to say hello. “You son of a gun,” he exclaimed. “You and your Spotlight Team just won a Pulitzer Prize for the Somerville investigation!”

Timothy Leland, a former reporter, managing editor and assistant to the publisher of The Boston Globe, lives in Boston and summers on Chappaquiddick. (Click on this link to see a short documentary on the Spotlight Team.)

Comments (10)

Comments

Comment policy »