So which unfortunate old schooner was she?

For the third time since the remnants of Hurricane Sandy raked the Island in late October 2012, the petrified wooden timbers and bent iron fastenings of a large sailing ship suddenly jutted out of the sands of East Beach on Chappaquiddick two weeks ago.

The fastenings, lined up in rusted regimental rows almost parallel to shoreline, showed how the ship might have lain broadside to the surf after she was driven ashore 150 years ago or more. A few gnarled old deck frames angling up out of the sand hinted at the strength of her construction and how much she might have heeled over once she came to rest on the beach.

It was clear what had disinterred the bones and pins of the wreck — the erosive forces of the blizzard of Jan. 23-24, whose northeasterly gales blasting over the eastern Chappy coastline at better than 40 knots drove surf high up the beach and pulled tons of sand back into Muskeget Channel.

Bill Brine of Chappaquiddick, exploring East Beach and Cape Pogue with his wife on Feb. 1, took pictures late that afternoon. His camera clearly outlined the shape of the ravaged hull, but it could not give us her name or her story.

Enter Arnold Carr, an Oak Bluffs marine biologist, legendary diver and president of American Underwater Search and Survey of Cataumet, a firm dedicated to finding and recovering evidence and relics from lost ships and planes. Mr. Carr saw the photo on Feb. 3 and began thinking about which vessel the East Beach wreck might be.

Working from old charts, newspaper stories and records collected from dives on wrecks all around Cape Cod and the Islands — many of which he and his company discovered — his initial idea was thrilling. It was possible, he said in an e-mail, that the wreck might be part of the schooner Christiana, sunk on Hawes Shoal about a mile offshore during a blizzard on the night of Jan. 7, 1866.

The gale lasted five days and nights, and the loss of the Christiana — as well as the excruciating fate of the only crewman to survive it — ranked among the most notorious disasters on Island waters in the 19th century.

“The most terrific storm has raged around our island that has been experienced for many years,” the Gazette reported on Jan. 12, 1866. “The wind has driven around us wildly, and the snow has come in overpowering, blinding blasts.” The day before publication, the tempest had only just settled down, “and we have not learned of the extent of the damage done, but many disasters must have occurred to the fleet of coasting vessels.”

Among those disasters was the wreck of a two-masted schooner carrying cement from New York to Boston. She was the Christiana, driven onto the shoals just off Cape Pogue on the first night of the storm. In the blizzard, her keel had shattered on the bottom and her anchor had swung loose and bashed open her hull.

The captain and four crewmen, including first mate Charles Tallman of Osterville, had climbed into the masts, where they clung for four days in sub-zero temperatures, whipping snow and ice. By the fourth day all were dead save Tallman.

When the wind and seas finally eased in the darkness of early Thursday morning, a surfboat manned by Edgartown seamen set out for the wreck from East Beach. At dawn they found a hideous tableau of dead bodies and wreckage. “It was accounted a dreadful sight by those in the boat,” The New Bedford Standard reported.

Another story described how “Tallman’s rescuers found him well nigh gone. He had spent five sleepless days and night without food or drink or warmth. The cold had been frightful, and a mere bit of frozen sail had been his only shelter from a marrow-chilling wind. The flesh had been torn from his fingers by incessant beating to keep warm.” One of his fingers had actually been severed.

Tallman was taken to Edgartown, where what remained of six of his fingers were trimmed off and his feet were cut down to elephant stumps. Money was raised to help him make a new start. Letter writers in the Gazette traded accusations and rebuttals that Edgartown had been dreadfully slow to send a boat out to the Christiana to see if anyone could be saved from the rigging.

Yet harbor ice had blocked even large ships from heading out, and four days into the storm, witnesses on Chappaquiddick, watching the wreck as well as the figures up in the rigging, described how “surging waves came rushing up from both sides of the vessel, and broke twenty feet high on the surging masts.” Tallman himself said later that no one could have safely reached him before the gale began to back down on his fourth night up in the crosstrees.

A year later, unemployable because of his amputations, he returned to the Island where the townspeople of Cottage City (now Oak Bluffs) built him an octagonal stand from which he could sell pictures of himself, as well as peanuts and the story of his ordeal to tourists just off the sidewheelers. Today the building is a souvenir stand adjacent to the Flying Horses carousel.

Is what turned up on East Beach the wreck of Christiana? Mr. Carr had planned to inspect the site on East Beach with a friend over the weekend, but ironically the extreme cold stopped them.

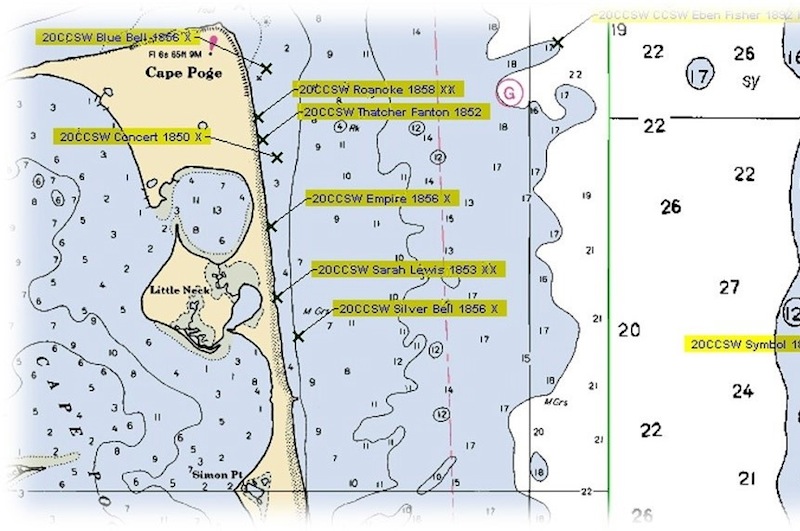

Meanwhile, he decided the relics on the beach probably aren’t from the Christiana. More likely, the ruins are those of the schooner Silver Bell, which maps say came ashore on East Beach in 1856.

A search of Gazette archives turned up no reports of shipwrecks on Chappy that year, though the winter was icy, blockading ships in harbors all around Cape Cod and the Islands for weeks at a time.

Possibly the map gives the wrong year for the wreck or possibly the Gazette carried a short item on the Silver Bell that was not found.Wrecks along the coastal highway of Vineyard and Nantucket sounds were all too common in that period. But the loss of the Christiana, and the fate of Charles Tallman, will stand out among them forever.

Comments (7)

Comments

Comment policy »