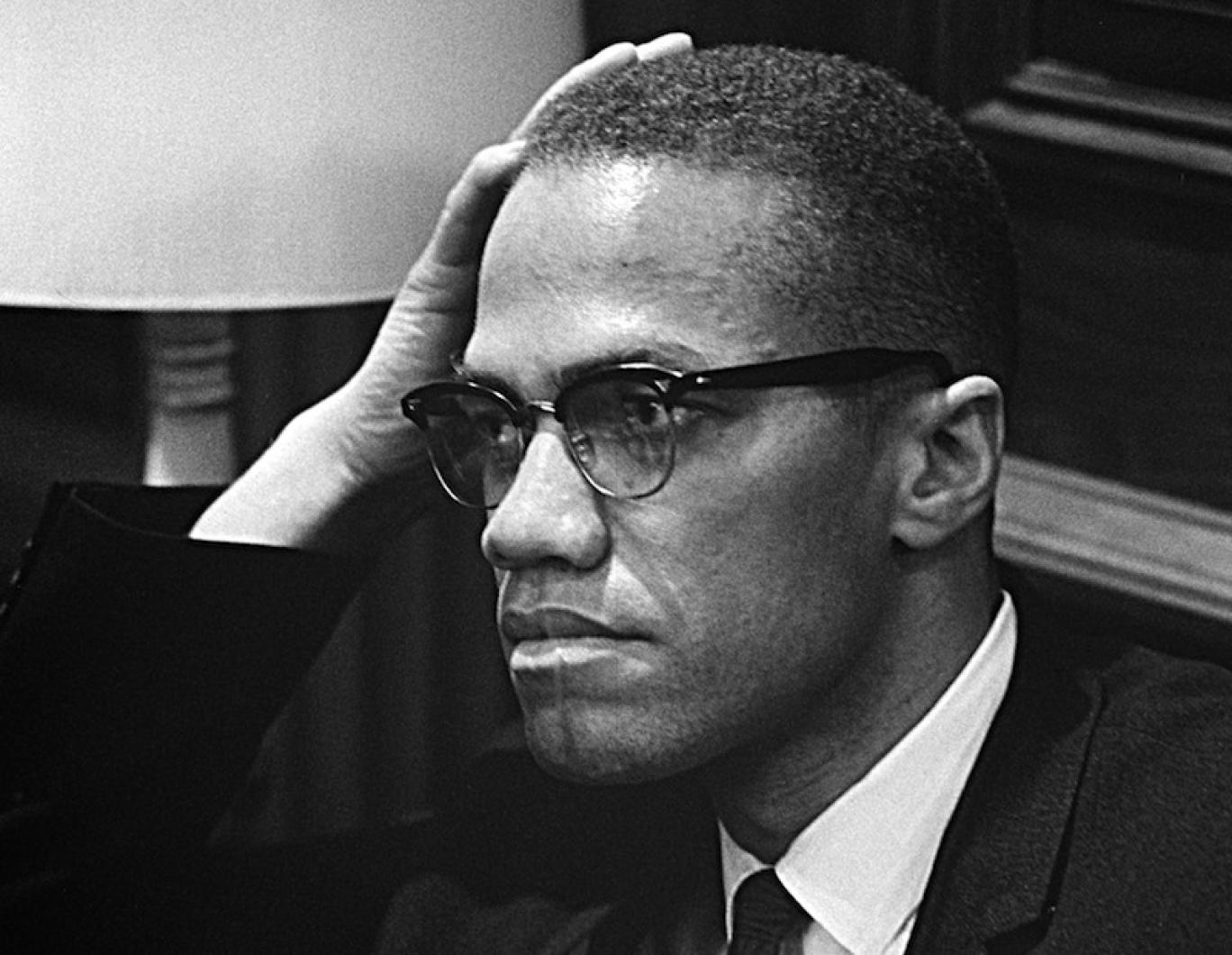

Fifty-one winters ago this coming Sunday, Malcolm X was cut down in a hail of bullets in a social hall in Harlem. He was 39, the same age Martin Luther King Jr. was three years later when he was cut down. By the last year of Malcolm’s life, these two men finally saw eye to eye after years marching down divergent paths.

Born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Neb., this African-American Muslim minister and human rights activist lived a short life of heated controversy. He was admired for championing his people while attacking a white establishment of hatred and bias. And he was denounced for the same reasons. He and his religion instilled fear in many hearts. Right or wrong, he had a profound influence on this country’s history.

At the time of his death, I was in the master’s program at Columbia University’s graduate school of Journalism in New York city, a city on edge. Seven months earlier, it endured one of its angriest summers. On July 16, 1964, on the upper east side of Manhattan, Thomas Gilligan, an off-duty white police lieutenant, shot and killed James Powell, an allegedly armed 15-year-old black student. All hell broke loose. (Sound familiar?) This triggered six nights of rioting, looting and vandalizing. At the end, one more was dead, 118 injured and 465 arrested, and the city was devastated.

“Law and order” became a rallying cry. Frustrations climbed quickly on both sides of the racial divide. Another head of steam was building as Malcolm pulled away from his church, the Nation of Islam, charging that the man in power, Elijah Muhammad, was unfaithful to the religion. Then another hell broke loose.

On Sunday, Feb. 21, 1965, Malcolm X stepped up to the podium to address the Organization of Afro-American Unity gathering of 400-plus in Manhattan’s Audubon Ballroom. A sawed-off shotgun appeared, then two semi-automatics, then wild commotion. He died with 21 gunshot wounds, assassinated by three black men with ties to Elijah Muhammad.

Before the burial on Feb. 27, Harlem observed what amounted to a four-day wake. By the end of this public viewing, nearly 30,000 people had filed past the body. I was one of them — but it wasn’t my idea.

On the morning of Feb. 23, I waltzed into my news gathering class at Columbia. The professor was calling out the day’s assignments. This meant you would go to a location, sniff out as many details as you could, return to the school and pound out a story as if you were actually working for a paper. Sometimes two students were sent, one to report, the other to take photos. In this one-year masters program you were expected to learn every job in journalism. By the end of the program, believe me, getting a real job was a vacation.

“Reisman — reporting! Aaronson — pictures! Unity Funeral Home in Harlem. Pay your respects to Malcolm X!”

Larry Aaronson and I glimpsed each other in grinning bewilderment, like those last movie close-ups of Bonnie and Clyde. A fellow student, a black woman, took a deep breath. “Now there’s a fun assignment. Good luck,” she said. “At least he wasn’t killed by white men.”

So off we went, two white kids venturing into that predominantly black neighborhood above Manhattan at a time just before the mass acceptance of the term African American, in the days just before the roiling surge of Black Power. We were armed with a spiral notebook, a couple of pens, a twin-lens Yashica and the personal baggage of a news media-inducing fear, thanks mainly to the Harlem riots which had scared, and scarred, everyone. And now I was acting and serving as part of that news media.

The line outside the funeral home was endless, a chain of mourners, observers and gawkers that extended for blocks. A cold overcast day added to the mood, which was mainly one of dignity, solemnity and sorrow, with an overlay of tension. Had they really captured all the shooters? Is there a sniper lurking somewhere? Do I really want to see a riddled body lying in state? (Amazing cosmetic work, actually).

Everyone in line was well dressed, in keeping with those times. Topcoats, fur coats, sensible wool coats, gloves, hats on both women and men. A few spots in front of us stood U.S. Cong. Adam Clayton Powell (no relation to James). We buckled up our courage and asked him for a quote and a photo. As Larry snapped away, Mr. Powell said: “A lid’s been kept on the frustrations and humiliations in our community and Malcolm was very instrumental in lifting that lid because that lid needed to be lifted.”

At the funeral on Feb. 27, the actor Ossie Davis delivered the eulogy at the Faith Temple Church of God. Later the funeral cortege for Malcolm X proceeded to the integrated Ferncliff Cemetery in the hamlet of Hartsdale in Westchester County, where his interred neighbors include many celebrities, black and white, and 15-year-old James Powell.

We got back to Columbia and I wrote my story. A week after Malcolm’s funeral came the first march on Selma. Many years have gone by. Many changes have come. But guns are still everywhere and black lives still matter.

Arnie Reisman and his wife, Paula Lyons, regularly appear on the weekly NPR comedy quiz show, Says You! He also writes for the Huffington Post.

Comments (9)

Comments

Comment policy »