A plan by a prominent Vineyard conservation group to restore the Mill Brook headwaters in Chilmark has run into fierce opposition from a nearby resident who says it conflicts with decades of observation at the site.

In a sharply-worded letter to the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs last month, Frank Dunkl, whose family bought land near the headwaters in 1963 and lives there still, argued that the project was based on assumptions and “junk science,” and demanded a more thorough environmental analysis.

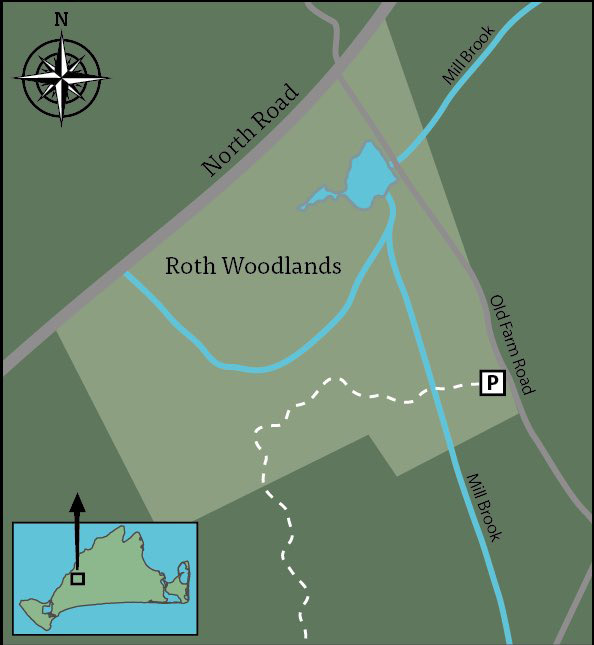

Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation, which received a 26-acre parcel from Georgia Roth in 1972, is hoping to remove two small metal culverts in an area known as the Roth Woodlands, where the Mill Brook originates. From there the brook winds its way south to Tisbury Great Pond, forming a series of small ponds along the way, including Mill Pond in West Tisbury.

The Mill Brook system has been the subject of a long-term planning effort in West Tisbury that supplied some of the data for the headwaters restoration project. But the Chilmark project itself is not part of the larger planning efforts.

According to an environmental notification form prepared by consultants at the Horsley Witten Group for Sheriff’s Meadow and submitted to EEA in February, the project aims to transform a small artificial pond into a freshwater wetland and cool-water stream network by installing an eight-foot concrete box culvert beneath Old Farm Road.

Sheriff’s Meadow has secured about $60,000 in state funding for the project, along with a $7,500 grant from the Daniels Wildlife Trust. Foundation executive director Adam Moore told the Gazette this week that it was likely the first project of its kind on the Vineyard to comply with Massachusetts stream-crossing guidelines.

In a separate conversation, Mr. Dunkl said he remembers when the existing metal culverts were installed in 1973, along with some large rocks, following an incident that involved a fire truck tipping over into the marsh and damaging the area. He recalled the culverts backing up only once in the last 50 years.

“That marsh almost dries up every single summer,” Mr. Dunkl said, arguing that any fish that made their way past the culverts would surely die in the warmer months. “They’d be boiled alive in the hot water and then get picked off by crows and other predators,” he said. He believed the new culvert would leave little or no water west of the road for most of the year.

But Mr. Moore has argued that more fish would be able to get through the new culvert at times of year when the water flows, and that the restored streams and wetlands would be less exposed to the sun and therefore more habitable for cold-water species such as brook trout, which have declined in the region.

He noted that temperatures in the pond exceed 90 degrees in the summer, which is enough to kill some fish. “The data I’ve seen shows that it’s actually the hottest one of the several ponds along the Mill Brook,” Mr. Moore said.

In his letter to the state in March, Mr. Dunkl raised several concerns, including the site’s proximity to a drinking well that once supported his family’s bottled-water company, and the potential effect on the aquifer. “Any draw-down of the nearby water table would cause this well to run dry, causing public health concerns and economic consequences,” he wrote, also mentioning possible litigation.

Mr. Dunkl argued that the new culvert would cause “extreme siltation” downstream, possibly endangering the state-listed brook lamprey and destabilizing the area for years to come, and pressed for a watershed-based evaluation of the project.

In his own letter to EEA, dated March 28, Mr. Moore noted the foundation’s respect for the Dunkls, who had donated a conservation restriction on their land to the foundation in 1979. But he also rebutted most of Mr. Dunkl’s arguments, arguing that the proposal was “more in keeping with the ‘forever wild’ goal of Ms. Roth than is leaving the stream in its current state, clogged up by a pair of undersized twin pipes.”

He wrote, among other things, that the well in question is not listed as a class A public water supply on the state GIS website, and that Mr. Dunkl had not responded to a request for more information about the well in 2014. He also argued that the restoration would expand the overall habitat for brook lamprey, and reduce road mortality by allowing turtles and other species to cross through the culvert.

“Sediment movement would only occur immediately after the culvert is removed,” Mr. Moore wrote.

In addition to the environmental notification form and approval by EEA, the project will also require a permit from the Chilmark conservation commission, and possibly the Environmental Protection Agency, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Martha’s Vineyard Commission (the entire stream is part of the MVC’s coastal district).

The project would also require additional funding before work can begin, although Mr. Moore said it was too soon to have a cost estimate.

Mr. Dunkl maintained that the project deserved more research, especially in regard to the volume and flow of water. And despite Mr. Moore’s assertion that the area contained no certified or potential vernal pools, Mr. Dunkl said he has observed at least six this spring. “They may or may not contain significant species,” he said. “But they are certainly a vital part of the ecosystem.”

He suggested that project engineers had relied more on projections and indirect data than on direct observation. “They tended to believe that what’s good for the goose is good for the gander,” he said. “This might be a wonderful project somewhere else, but I don’t believe that it is appropriate for this particular location.”

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »