It has a face only a mother could love.

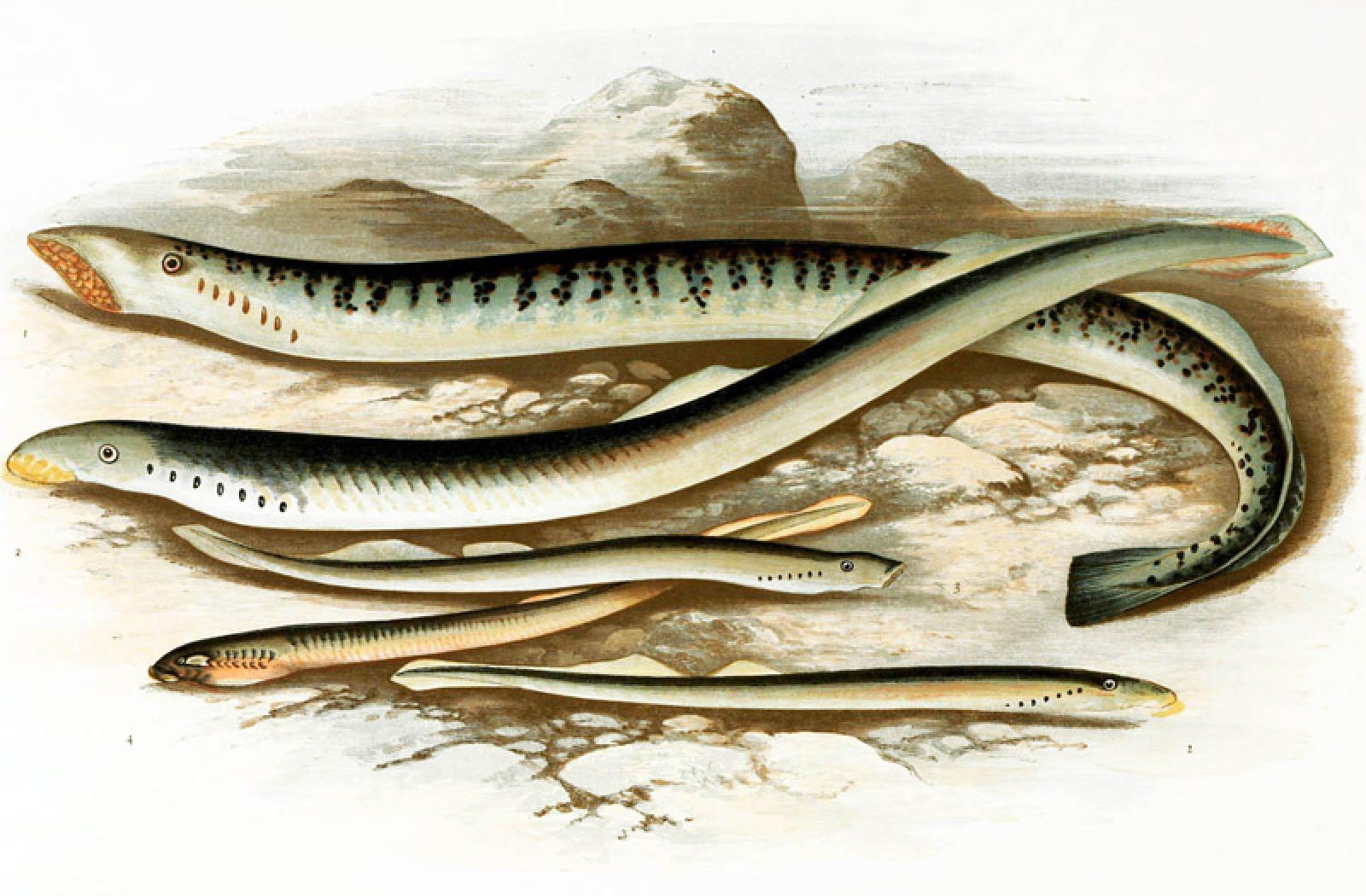

The lamprey, a jawless fish that resembles an eel, has been called the most hideous fish in the world.

I can’t say I agree. Truly beauty is in the eye of the beholder and that lamprey sure looks good to its mate.

To be fair, this animal is not beautiful by most standards. Ranging in length from five to 40 inches long, the fish’s most disturbing characteristic is its toothed, funnel-like sucking mouth, which has been called the most ghastly mouth on earth. This mouth can be used to suck blood, eat flesh, or just scare the bejesus out of everything in the water and on land, including one Islander who last week reported an American brook lamprey in an up-Island stream. Her take was simply “ick.”

Try to keep an open mind — or maybe an open mouth — when considering this creature. Though certainly not the belle of the ball, lampreys have a unique natural and culinary history, even if it will never be a Cinderella.

Lamprey, as a species, represents an ancient lineage of vertebrates — though it has no bones about it, but, rather, a cartilaginous skeleton. Our local rare freshwater species, the American brook lamprey, is not often seen, and is one of only a dozen brook lamprey populations in our commonwealth. The last Island report I received was back in 2009 and it is listed as threatened in the state.

How ancient are they? Paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould remarked in his book Eight Little Piggies that “we now recognize these jawless fishes (class Agnatha) as the oldest vertebrates and precursors of all later forms, ourselves included.” These ancient ancestors of ours, the Agnathas, as Mr. Gould notes, survive today as lampreys and their distantly-related cousins the hagfishes. But what happened to their more adventurous descendents? Well, as it happens, they became a sub-group called vertebrates, which includes lions, tigers, mice, and you and me.

As for the lamprey’s disappearing act from Island local history, it is not at all surprising since much of brook lampreys’ lives are spent in larval form, called ammocoetes, in the mucky bottom of streams. After three to five years, the lamprey ammocoetes become adults. Their only job at that point is to mate before taking their final breath. In a final show of strength, the male wraps itself around its partner and literally squeezes the eggs out of her.

The mating death is nothing compared to the fate of the sea lamprey. This much more common anadromous (ocean-dwelling, freshwater-spawning) sibling of our local brook lamprey was at one time a gastronomic specialty — unfortunately for some.

King Henry I of England is believed to have died from a “surfeit of lampreys,” after over-consuming this delicacy. His dish was prepared by soaking the lamprey “in its own blood for a few days,” a clear invitation to disease. The specific recipe called for “taking a living lamprey, and let him bleed at the navel, and let him bleed in an earthen pot.” This royal fatality is hardly surprising, since this treatment does sound deadly to both the animal and the eater.

The French also had their way with lamprey. Bordelaise, a French demi-glace sauce, was recommended as the best sauce for sea lamprey, which are reputed to taste a bit like squid. I haven’t tried it, so I can’t say either way.

But certainly we wouldn’t want to eat our local variety, due to its rarity and the protection its threatened status provides. And, would you really want to be mouth-to-mouth with any lamprey? Just pondering the life and times of this creature is truly enough food for thought for even the most adventurous eater.

Suzan Bellincampi is director of the Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary in Edgartown, and author of Martha’s Vineyard: A Field Guide to Island Nature.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »