At the college radio station where I worked at Rollins College, the poster hung on the wall. A scrawny little thing with a few flaccid chest hairs, greaseball hair tumbling down as much Guido greaseball as Latino playa — naked but for a pair of skimpy bikini panties and a cross.

Prince hadn’t broken wide when his song Controversy found WPRK, there on Rollins’s manicured Spanish style campus on the lake. My mother came to watch me turn the radio show on one morning, alone under the library before Chris Russo my news and sports guy — who would later become the radio personality Mad Dog Russo —got there.

As the generators hummed and the equipment whirred and warmed up, I ran around flicking light switches, grabbing logs and clipboards, tearing the latest Associated Press news feed. I found her, hair teased high and wide, three platinum stripes rising out of the impossibly immobile Lady Bird Johnson ‘do, staring intently at the rumpled poster.

Pressing the Marlboro 100 to her lips, her eyes narrowed as she dispassionately inhaled almost the entire thing. The tip burned angry red, intensifying as she sucked in. When she finally stopped drawing the burning tobacco into her lungs, she let out a plume of smoke, turned to me as I settled behind the turntables and board, preparing to put the radio station on the air.

“And what in the hell is that?” were her only words. Flat, cold, appalled.

“His name is Prince Rogers Nelson. They call him Prince. From Minneapolis.”

She inhaled what was left of her cigarette, dropped it into her coffee.

“He looks like a faggot.”

And there you go.

Prince Rogers Nelson, like James Brown, like Stevie Wonder, like Rick James, carved deep veins of funk. Grooves you could do the laps in, beats that would bounce you like a little kid on a trampoline.

My gateway drug had been rollerskates. Fat wheels, stiff leather, laced way above the ankles. When I Wanna Be Your Lover played, it was so juicy, so emollient, it felt like that polished hardwood floor would push you by virtue of the silky pop grooves. And the way he squeezed his voice in the end? Oh, yeah!

There were no little boys like that at any of the prep schools I went to: sensitive, melting gender, sprawling across rock and rhythm and blues and pop and funk. But Prince did it with such insouciance, such bravado, such luster, you couldn’t walk away.

If Rick James was hard and ghetto, there was something so bohemian about the man wearing ladies clothes long before arena rockers found Frederick’s of Hollywood.

Looking up through that thick black hair, he was a doe-eyed sylph who was all tease, then taunt, then . . . well, the mind bucks. Which was exactly the point. I loved him. Nice girl from the suburbs, plaid skirt, white cotton blouse, I couldn’t look away. Unlike my mother, he didn’t repulse me. He excited a curiosity about what happens when hormones run wild. Even if I remained a nice girl, it’s good to know what happens when you close that door.

Prince became my own private rebellion. If my street school friends knew about Earth, Wind and Fire and Rick James’ Superfreak, I knew something even more out there. Prince was mine, and I liked it that way.

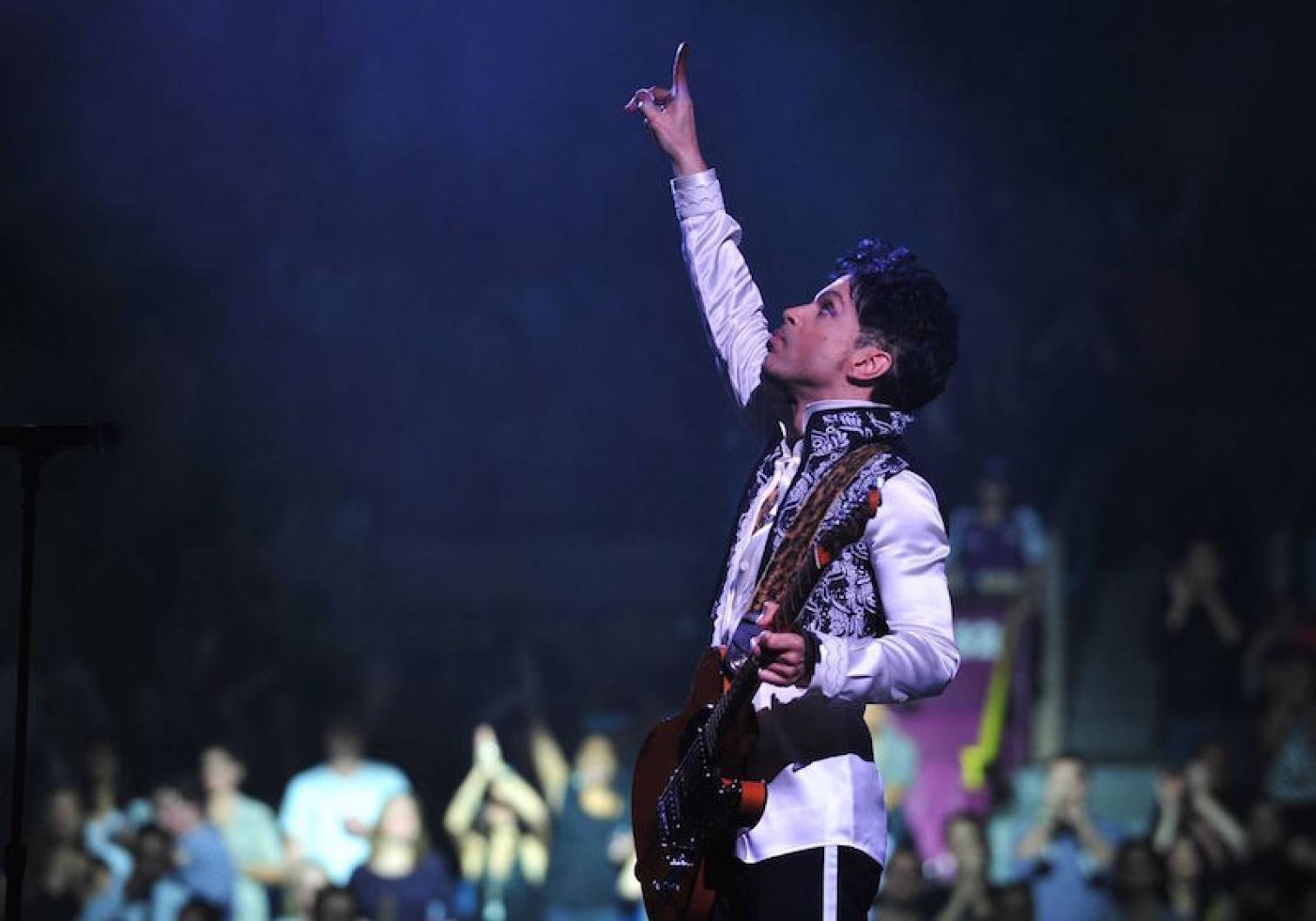

He hit Miami like a hurricane, blowing into the Orange Bowl with full gale force for the Purple Rain tour. This tiny little man who danced like a chicken on a hot plate, downstroking his electric guitar and yowling with the demand and gratification of a true sexual avatar.

Yes, yes, yes. Garnering an invitation to the post-show party at the glorious, high end South Beach when it was busted Club X, I chewed my straw and watched the wide curving stairway hoping for a glimpse. When he showed — somewhere between two and three in the morning — it was old school glamour. A meltingly luxurious suit in a pastel so pale, it was unidentifiable. Tiny like a jockey, but a presence that consumed the room.

Sheila E was with him, laughing into her hand. Caramel hair falling in waves and curls, a pencil skirt slit up, lace stockings and a satiny blouse whose tailoring seemed almost to be designed to second skin her.

Rock and roll didn’t look like this. Nothing did. I was gobsmacked.

Years later, having cashed out my journalism chips to take a job at Sony Nashville, I saw Prince again, up close, at the MTV Awards. Even in rehearsal, with his energy pulled in, he held nothing back from that guitar. It was man and music, entangled, thrashing, pressing and seeking. It was, perhaps, the aural equivalent of sex with an instrument — and it felt good.

And when Screwdriver dropped out of the blue last year, it was just as alive, just as much voltage rushing through it. An entire day, I did nothing but play the YouTube with the flimsy little video over and over. Kept sending the link to friends, loving every Facebook re-posting or tweet or gushing email reply. That sense of the groove coming from the inside out? I never recovered, and all these years later, it still hit me in the face and dropped me to my knees.

I could go on and on. But I can’t. I’m crying again, sitting here in some deep Alabama truck stop, people who were never touched by the music milling by in search of a hot shower, a little food, some gas or coffee.

Not me. I had to pull over when an editor mentioned it to me in a phone call. Had to start writing, had to try to remember it all: the way my blood felt like schools of little fish nibbling my veins when his music was loud, the pulse racing when I glimpsed him at X, or my jaw went slack just watching him push that glyph-looking guitar to places I didn’t know existed.

People are looking. What can you say? They think you’re some silly teenager in a flashback moment, lost on a tide of who you were when you didn’t know any better. They’re wrong, of course. Prince is the one who brought a freedom and a knowledge, a conquistador’s brio and a hunger of wolves to our lives. Like the snake in the garden, he gave us an apple that tasted like music and sex and love.

Prince was 57. Too young, not enough, no reason.

The truck stop has no cut rate albums to buy, no For You, Prince or Dirty Mind. Not even a bad second generation Purple Rain or Parade or Sign o’ the Times. It is raining now, just a little, a good cover for my tears.

US 280-E beckons. Miles to go before I sleep, driving and crying in what most certainly won’t be purple rain. But before I pack my things, back up and drive away, do me a favor: remember, all we have is right now. Today, do something bold. Tell someone how you feel. Wear that expensive thing you’re saving. Drive a little too fast if makes you more alive. Turn up the music, especially, and let it play.

Holly Gleason is a frequent visitor to the Vineyard and contributor to the Gazette. She is based in Nashville and has written for Rolling Stone, Spin, CREEM, The LA Times, New York Times, Oxford American and No Depression.

Comments (11)

Comments

Comment policy »