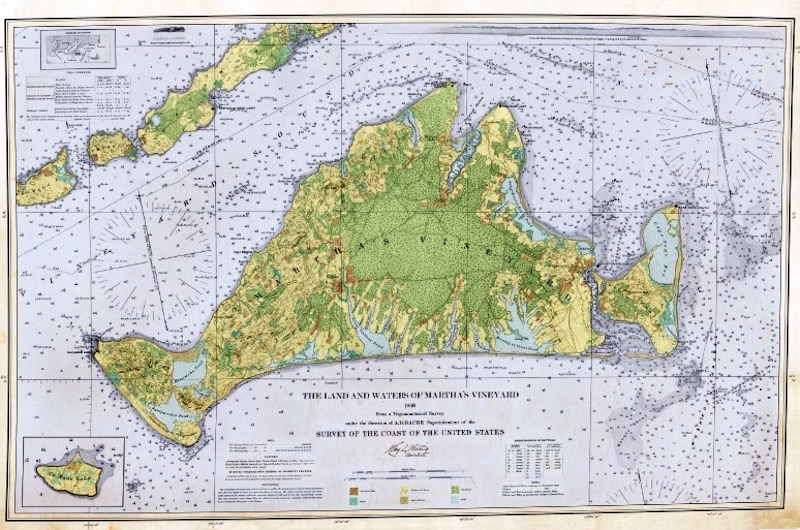

Henry Whiting came to Martha’s Vineyard in the early 1840s as the United States chief cartographer. He was working on the U.S. Coastal Survey Chart, which mapped more than 25,000 lineal miles of shoreline, including the entirety of Martha’s Vineyard. He and his team spent over a decade detailing the roads, ponds and topography of the Vineyard and other coastal communities, creating an intricately detailed and incredibly accurate map.

David Foster, ecologist and director of the Harvard Forest, wanted to do something with that map, what he called the 1850 map. He decided to focus on the Vineyard, where he has visited since the 1990s to study the forest. He searched for a copy of the Coastal Survey Chart from which to study the Vineyard, but was having no luck. Then one day, while visiting friends on the Island, he spotted a pristine original chart hanging on the wall of their Lagoon Pond home.

Using that chart, Mr. Foster was able to not only focus on the Vineyard, but he also updated the map providing color and new details. At a talk on Thursday night at the Agricultural Hall, hosted by the Polly Hill Arboretum and the Agricultural Society, Mr. Foster discussed the significance of this map of the past in relation to today’s Island topography.

Mr. Foster said Mr. Whiting fell in love with the Vineyard when he came here. He lived on a small farm in West Tisbury and later helped found the Agricultural Society in 1856.

“Henry Whiting took great interest in the Vineyard, so he resurveyed the shoreline repeatedly,” Mr. Foster said. “We have a 50-year record of just his work of the way the Vineyard changed over time.”

Mr. Whiting’s map provides a long term study in erosion, and, when compared with today’s topographical maps, it also tells a story in trees. The mid-1800s were the time of heavy deforestation in New England.

“The single greatest process that has shaped Martha’s Vineyard and shaped New England landscape since the deglaciation, is really the arrival of European people and other people over time, and the gradual deforestation and the eventual reforestation of the landscapes starting in the 1600s,” Mr. Foster said.

The peak of deforestation was reached in 1850, but then the focus on agriculture shifted, thus changing the landscape again. “The land on the Vineyard came back quite naturally with very little help,” Mr. Foster said.

Mr. Whiting’s map shows that almost all of the Vineyard, except for the very middle, was pasture land at that time. Species such as grasshopper sparrow, bobolink and meadowlark flourished in that landscape but are now in decline due in part to the change in habitat.

“I’m utterly convinced in order to understand the present we have to understand the past,” Mr. Foster said.

The map was scanned at a resolution of 1,000 dots per inch to showcase the details.

“This map is absolutely extraordinary...this is unusual for maps of this era... they show not just cultural details but they show the landscape and the vegetation,” Mr. Foster said. “Green being wood lots, yellow being pasture land and hay fields, brown being tilled land, and they even show in pink, orchards. Every road is shown and many of the fence lines are shown. With that map one can reconstruct the Vineyard quite nicely.”

For example, even during the time of heavy deforestation of the 1800s, a forest much older than the United States of America survived, nestled in the middle of the Island. This forest continues to exist today, located around the airport, bike paths and the disc golf course.

But although New England has many more forests now than it did during Mr. Whiting’s time, Mr. Foster cautioned that deforestation is happening again.

“All across New England and increasingly on the Island for the first time since Henry Whiting’s days, New England is now losing forest, because we are developing. We are plunking big houses down,” he said.

Because the map is both a window into the Vineyard’s history and a lens with which to view our present day Island, Mr. Foster suggested taking the journey by riding in the passenger seat, the better to be able to withstand the bumps in the road.

“One gets to Five Corners and you’re amazed at how much the landscape has changed, and you’re in big trouble,” he said.

The Henry Whiting 1850 map is available for purchase at the Polly Hill Arboretum or by phone at 508-693-9426. Maps also available at Bunch of Grapes, Granary Gallery and the Martha’s Vineyard Museum. To read more about the map and David Foster’s forthcoming book A Meeting of Land and Sea: Nature and the Future of Martha’s Vineyard visit mvlandandsea.com and to explore a digital version of the 1850 map visit mv1850.com.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »