Tom Hodgson of West Tisbury has a few turtle tales to tell.

The stars of his stories have a very different perspective than you or me. They stand only about a few inches above the earth and see the world entirely from the ground up. It can be dangerous down there. Turtles are slow and vulnerable, so even crossing the road can be deadly. Meeting up with humans might not be a day at the beach either.

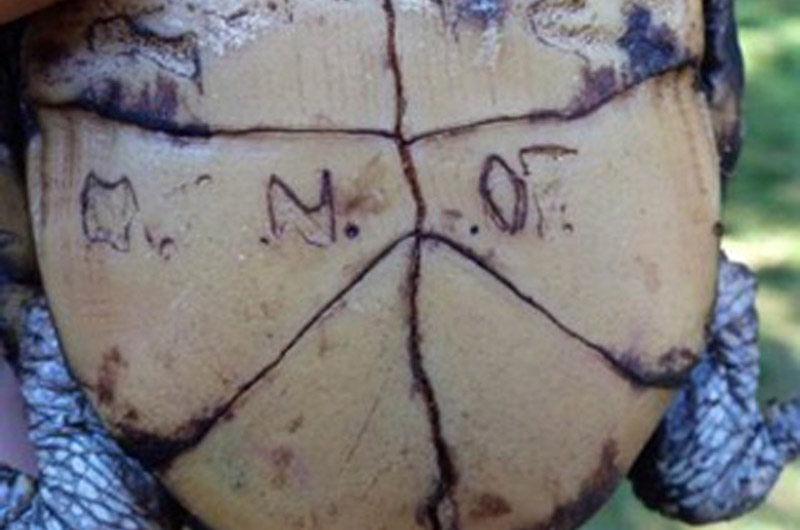

Turtles do have that well-known shell for protection. But last week, Tom photographed a box turtle that had been down on its luck. Someone had carved their initials and maybe a date on the box turtle’s carapace (top shell), and Tom observed damage to the shell and foot that could have been caused by a predator, car or other calamity. This animal was clearly a survivor, not letting those injuries slow her down.

This turtle was a female, as indicated by its eye color and plastron (bottom part of shell). Male box turtles have red eyes and a concave plastron, while female box turtles have a flat plastron and yellow or brown eyes. Males may also have more colorful legs and head, thicker tails and longer claws.

Interestingly, this wasn’t the first time Tom found a turtle whose shell was engraved. In 2006, Tom had found a very old and unusual box turtle that was carved with initials and a series of dates. The earliest date was 1861. Let that sink in. If the date was accurate, that box turtle had been alive during the Civil War, when Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as President. and was still crawling about West Tisbury during President Bush’s time in office.

Finding turtles must be a Hodgson family affair. His daughter found this same 1861 turtle in 1998. Also carved on the plastron of this turtle were the dates 1881, 1932, and 1955.

That would make the turtle at least 145 years old and perhaps one of the oldest known wild box turtles. Typically, a box turtle’s life span ranges from 25 to 80 years old, so this turtle might have been a geriatric record breaker.

It is not surprising that both Tom and his daughter found the same turtle, since turtles are not known to explore far and wide. In fact, they have very small home ranges and generally do not travel further afield than a few acres during their entire life. Box turtles also have high nesting site fidelity, so it is not uncommon to see them in the same place year after year.

As interesting as it is to be able to determine a turtle’s age though this carving method, it is generally not a good idea. While the turtle may not feel pain during the cutting, the shell can be damaged, and/or weakened, causing harm to the softer insides of the animal. A turtle’s shell is made up of layers of keratin, the protein found in your fingernails.

It is just as easy, and more non-invasive, to capture their beauty and age using basic technology, even if these methods won’t be maintained over generations. Draw or photograph the shell patterns on the carapace to identify and track the box turtle, since these designs can be unique to the animals and distinctive enough to identify individuals.

If you don’t have Tom Hodgson’s skill or luck in finding turtles, here are a few tips. During the summer, box turtles are most active in the morning and evening, especially after a rainfall. They like to nest in loose sand, and can find a great spot on the sides of driveways and roads, in the garden, and even in mulch or woodchip piles. If you have seen one in an area once, remember you will likely see it in the same area again.

And if you do find one, be sure to handle it with care, resist the urge to inscribe it, and never remove it from its home range. Remember, box turtles are protected species in the state of Massachusetts and are thus safeguarded by rare species regulations.

Tom and his family will continue to be on the lookout for the 1861 turtle. This may be just the week for them to get lucky. After all, the turtle was around when Lincoln was President and was here in 1874 when President Grant vacationed on Martha’s Vineyard. Perhaps the aged turtle might consider another appearance during President Obama’s visit this week. Yes, we can keep hope alive.

Suzan Bellincampi is director of the Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary in Edgartown, and author of Martha’s Vineyard: A Field Guide to Island Nature.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »