Martha Hall Kelly’s interest in World War II began with stories from her mother. She told her that when she was 14 years old and living in West Tisbury, she watched World War II soldiers march by on their way to train in Aquinnah.

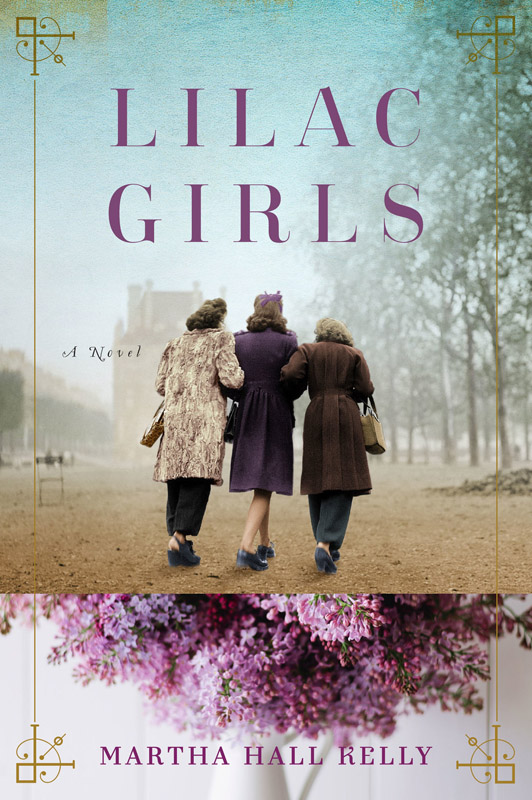

Decades later, Ms. Kelly worked as a copywriter and raised three children before writing her first novel Lilac Girls, which takes place during World War II. The novel was published this spring and became a New York Times bestseller within weeks.

Lilac Girls tells the true story of Caroline Ferriday, a New York city philanthropist who worked at the French Consulate during World War II and helped rescue 35 Polish women from the Nazi concentration camp Ravensbruck. The women were the subjects of experimental operations Nazi doctors conducted and were known as the Lapins, or Rabbits. The novel is told from the perspective of three women whose paths eventually cross: Caroline Ferriday, a German Nazi doctor, Herta Oberhauser, and the fictional Kasia Kuzmerick, a young Polish girl whose character is based on one of the Rabbits, Nina Ivanska.

In the early 2000s, Mrs. Kelly stumbled upon an article in Victoria Magazine, entitled Caroline’s Incredible Lilacs. She carried the article around in her wallet until she decided to visit the Ferriday House, which was only a few hours from her home in Connecticut. When she walked through Caroline’s room, she saw a photograph of a group of smiling middle aged women. Her tour guide said that the women were the Rabbits, whom Caroline had brought here and rehabilitated after the trauma they experienced at Ravensbruck.

Mrs. Kelly was shocked that the story had not yet been told.

“She didn’t toot her own horn a lot,” she said in an interview at her home in Chilmark. “It was that generation when people just did good things.”

Ms. Kelly was fascinated by Ms. Ferriday, and read everything she could about the Rabbits, Ms. Ferriday and Ravensbruck. It was only when an editor friend encouraged her to write the story down that Mrs. Kelly considered beginning a novel.

“I have never taken a creative writing class or anything,” she said. “How do you write a novel? I had no idea.”

But Ms. Kelly dove headfirst into the full story. She read letters, found people who personally knew Caroline Ferriday, and even visited Poland, Germany and Paris. Last April, she visited Ravensbruck a second time for the 70th anniversary of its liberation, where she met five of the Rabbits, one of whom was named Stasia. She was a Rabbit at age 14 and had been operated on four times. Stasia is now 95 years old.

That visit had a profound effect on the author. “I had to come home and rewrite the end of the book,” she said. “She was just so forgiving and grateful.”

Ms. Kelly said she wanted to understand all sides of the Nazi story, especially the U.S. policy of isolationism and Nazi totalitarianism. She dedicated a full year to researching Herta Oberhauser, the female defendant in the Nuremberg Trial who had killed healthy children and operated on many of the Rabbits. Ms. Kelly read her letters and books to understand why the doctors and camp staff did what the did.

“Once I spent that year researching that Nazi subculture, I understood her so much better,” she said, shuddering. “It was terrifying crawling into her skin, but it was necessary. To have that kind of hatred is just so scary.”

Ms. Kelly’s novel covers the perspectives of women from three different countries, which she says helps with the flow of the novel and contributes to the political viewpoints of each country.

“I wanted to go back from Germany and Poland, and have a little rest in New York,” she said.

As she researched more into Ms. Ferriday’s family, Ms. Kelly discovered that she came from a line of achieving women. Ms. Ferriday’s mother had helped out during the Russian Revolution and her grandmother had nursed wounded soldiers on the frontlines at the Battle of Gettysburg. Ms. Kelly plans to write a prequel and a pre-prequel to Lilac Girls to tell the stories of these two women.

The process will be easier, she says, because she knows to write in scenes and timelines, but most important, to fully immerse herself in the time periods.

“I love particularity in writing. I just tried to read as much as I could of writing from that time,” she said.

Part of the reason why Ms. Kelly felt she must tell this story is because Caroline never married or had children to carry on her legacy. Her incredible story has also been lost over the years because of her modesty.

“We really need more people like Caroline Ferriday who do things simply because they are the right thing to do,” she said.

Martha Hall Kelly will appear on Thursday, August 4 at Noepe Center for the Literary Arts, 104 Main Street in Edgartown, for a book talk and signing.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »