On an early morning this week, Chris Schillaci loaded a cooler full of ice into an Edgartown shellfish department boat, and along with shellfish constable Paul Bagnall raced out across the waves to the Middle Flats, about a half mile outside Edgartown Harbor.

A few small dots in the distance grew larger, and three figures in orange rain gear could be seen at work on the ocean, power-washing equipment aboard an oyster raft and pulling up brown cages from the bottom.

The shellfish department boat slowed down and began rocking in four-foot waves.

“It’s a hardy crew out here,” said Mr. Schillaci, a Division of Marine Fisheries biologist who monitors the Island’s oyster farms for Vibrio bacteria, which has become a major health concern in recent years.

Spearpoint Oysters is among the four Katama Bay farms experimenting in the outer harbor – one of several new approaches to dealing with Vibrio on the Island. Water temperatures around the Middle Flats are about eight degrees cooler than in the bay, which gets into the 80s in the summer – and less conducive to Vibrio, which grows on oysters and may cause illness and death in humans.

“The big interest has really blossomed in the last two years,” Mr. Schillaci said after collecting about 30 oysters from the crew and covering them with ice in the cooler. “The water temperature, the productivity, all of that, it seemed less conducive to Vibrio. What we’re doing is testing that hypothesis.”

Harsher weather in the winter limits work in the outer harbor to the warmer months, but the cooler water has an additional benefit of preventing the oysters from spawning, which makes them more palatable throughout the summer.

The DMF now requires shading aboard the 12 rafts in Katama Bay, and a one-hour limit before oysters must be iced, among other precautions. So far, the measures seem to be working, with only one confirmed case of Vibrio this year, despite one of the warmest summers on record. (It takes two to four cases within 30 days to close the bay.)

A new study published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that climate change and warming seas may add to the challenges of controlling Vibrio in the Northern Atlantic, although Mr. Schillaci argues that the local conditions don’t necessarily reflect to the bigger picture.

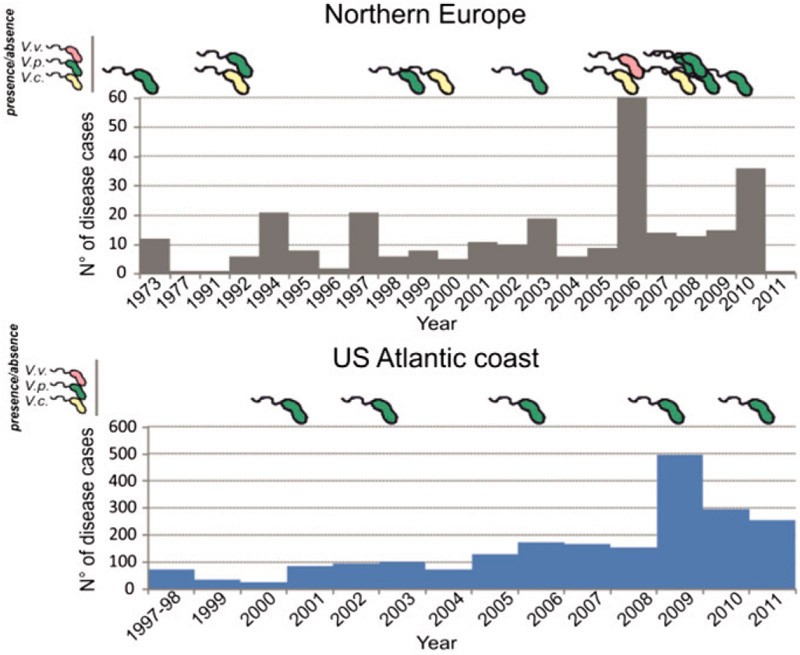

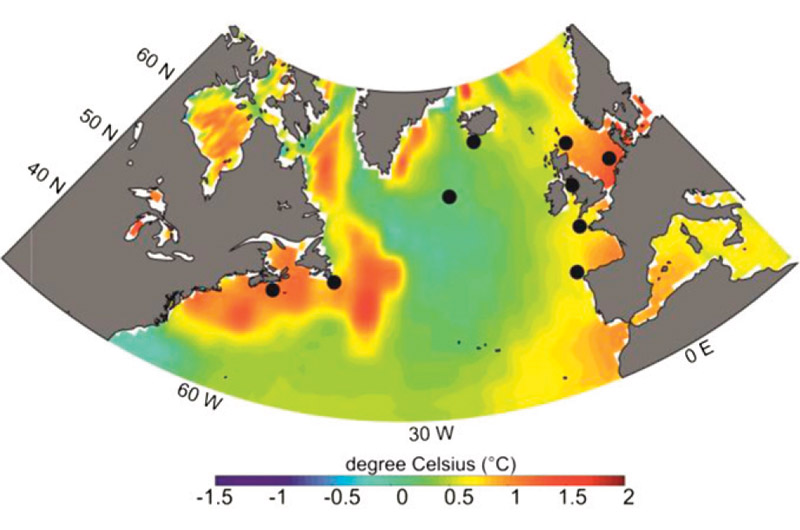

The study is likely the first to link climate change, Vibrio abundance and illness in the North Atlantic, and has received wide attention since its release on August 8. Researchers extracted DNA from a global archive of plankton samples, revealing a nearly six-fold increase in the abundance of two Vibrio species over the last 54 years. The increase correlated strongly to both increasing sea surface temperatures and the rate of illness in humans.

“As the climate warms further, and as the temperature of the ocean continues to increase, I think we will find that there will be a selection for these kinds of bacteria because they divide quickly,” Rita Colwell, a professor at the University of Maryland and a lead author of the study, said this week. “I think this is a kind of canary in the coal mine for climate change and human health.”

None of the plankton samples came directly from the waters around Massachusetts, although that area is considered among the fastest warming in the hemisphere. The North Atlantic in general has warmed rapidly since the 1950s (about 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit), with a sharp spike after 1990, corresponding to a similar spike in marine Vibrio abundance.

The DMF has worked aggressively in recent years to reduce the risk of food-borne illness, doubling down on its work with growers, restaurants and wholesalers in the state. But Vibrio parahaemolyticus, first documented here in 2013, has led to a number of closures, including a two-week closure in Katama Bay at this time last year.

Mr. Schillaci welcomed the new study, but stressed that its findings provide only a basic correlation between Vibrio abundance and illness.

“Total Vibrio hasn’t been the problem in New England, as far as resulting in illness,” he said. “It’s been pathogenic strains of Vibrio, which don’t always correlate with the total Vibrio. Vibrio is supposed to be here,” he added. “It’s the most common marine bacteria in the world, and there’s a ton of different species.”

The study focuses on Vibrio parahaemoliticus and Vibrio vulnificus, both of which are associated with high mortality around the world. But those are only two of the more than 110 recognized species, each of which includes many strains.

“Looking at total Vibrio or even at parahaemoliticus, the one that causes the majority of the gastric infections, doesn’t give you a clear concept of risk,” Mr. Schillaci said.

In any case, Katama Bay faces a tough challenge in controlling its particularly virulent strain of Vibrio, which is thought to have originated in the Pacific Northwest.

“Compared to other parts of state that have had far less illness, Katama has lower total Vibrio, lower numbers of Vibrio, but results in more illness than other areas,” Mr. Schillaci said. “Yes, there’s a warming temperature trend, and yes, that’s going to be good for Vibrio. But we don’t know if that’s going to increase the pathogenic strains.”

Ms. Colwell noted the study’s relevance to New England in general, and encouraged continued monitoring among oyster growers. She also advocates for pasteurization (although she acknowledged that growers often frown on the process), and depuration, which involves placing the oysters in clean water to help purge them of contaminants before they go to market. “Whatever can be used to reduce the potential risk is a good thing to do,” she said.

In light of the numerous strains of Vibrio in North Atlantic waters, she questioned the likelihood that the Katama strain had originated in the North Pacific.

“I think there are plenty of naturally occurring strains along the East Coast,” she said. “We’ve isolated them in the Chesapeake Bay and off the coast of Maryland and Delaware. I have not personally done the research in New England, but I would make a wagered guess that they are present there.”

She noted that the two species examined in the study may be fatal for people with compromised immune systems, but she was especially worried about Vibrio vulnificus, which causes infection through open wounds and is the leading cause of seafood-related death in the country. Mr. Bagnall and Mr. Schillaci said they were unaware of any wound-related cases of Vibrio on the Island.

The study also draws a connection between warming temperatures and the abundance of phytoplankton in the ocean, although that relationship is not as well understood. Ms. Colwell said algal blooms such as the ones that affect coastal ponds on the Vineyard may spur the growth of more Vibrio, as long as the algae attracts zooplankton, which decomposes and provides energy for the bacteria.

Looking ahead, she believes the study will spark more localized studies in a similar vein. Some experts have even suggested that Vibrio be used as a standard reference organism such as E. coli. She hoped other groups, such as the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, may also have stored samples that could be used to build on the study.

Meanwhile, the DMF will continue monitoring Katama Bay, with help from the Edgartown shellfish department and funding from the Interstate Shellfish Sanitation Conference, which sets national standards for shellfish that cross state lines and has made Vibrio reduction a high priority.

“There are some areas that seem to produce more than their fair share of illnesses,” Mr. Schillaci said, as the sun rose higher over the bay and he

headed back to shore with a cooler full of oysters. “We are just trying to identify what causes that, and ways to mitigate that without putting an undue burden on the industry.”

“It is early in the process, but it already is providing some benefits for us, as far as illness reduction. So we’re hopeful.”

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »