Vineyard residents are highly concerned about ticks and tick-borne illness, according to a newly-released community survey in which 79 per cent of respondents said they would support a significant reduction of the Island’s deer herd to address the problem.

The online survey, conducted in August by the Vineyard Gazette in cooperation with the Martha’s Vineyard Boards of Health, drew 1,311 respondents, roughly equally divided between full-time residents and people who spend part of the year on Island.

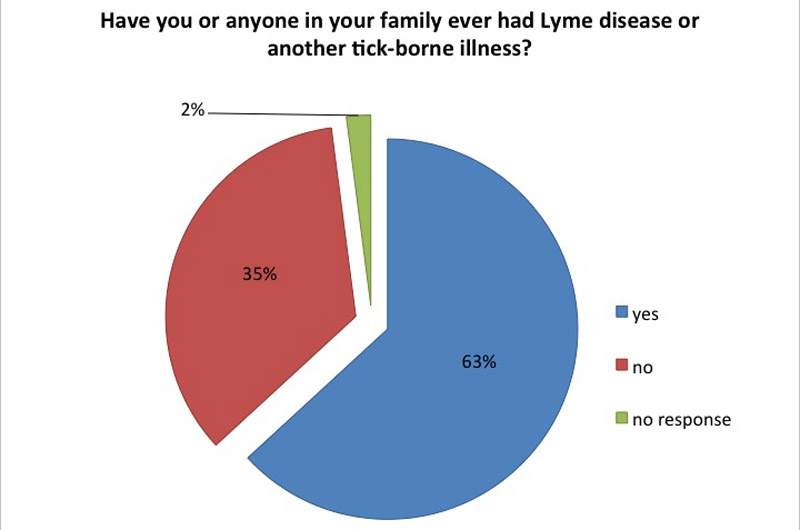

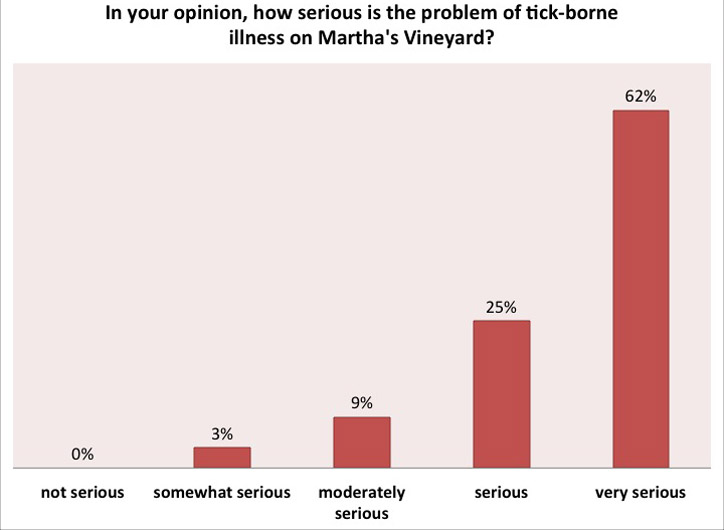

Sixty-three per cent of respondents said they or a family member had personally contracted Lyme disease or another tick-borne ailment, and 87 per cent called the problem of tick-borne disease on Martha’s Vineyard “serious” or “very serious.” Three per cent said it was only somewhat serious and less than one per cent considered it not serious.

Martha’s Vineyard has among the highest per capita rates of Lyme disease and other tick-borne illness in Massachusetts and the United States, according to data from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health and the Centers for Disease Control. These illnesses, which include babesiosis and anaplasmosis, can cause serious symptoms and may be life-threatening.

The idea of a community survey grew out of conversations between the Gazette and representatives of the boards of health’s tick-borne illness prevention program and was designed to test community attitudes about the seriousness of the problem and potential activities aimed at reducing its incidence. The survey was circulated by members of the boards of health, posted on various social media channels and distributed by email to about 12,000 Gazette readers. To guard against individuals filling out the survey multiple times, a mechanism was employed that prevented more than one response from the same computer or mobile phone.

The boards of health website at mvboh.org has a section on tick-borne illness that includes videos, tips and research on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the various tick-borne illnesses found on the Vineyard. Survey results showed, however, that less than a third of those responding had consulted the site.

But every measure suggested in the survey to improve public awareness of the tick problem and to reduce the Island’s tick population won strong support from respondents. In addition to culling the deer herd, more than 87 per cent of respondents supported spending town money to provide free or low-cost “tick tubes” to reduce the number of ticks feeding on white-footed mice, and 74 per cent supported spending town money on a professional to provide public education.

An analysis of the results showed equal support for all measures among year-round and part-time residents.

The survey also drew hundreds of comments, ranging from calls for more research to demands for immediate action.

“It is disappointing that Vineyard authorities are not taking more concrete, aggressive steps to deal with this grave threat to the people of the Vineyard,” one respondent said.

“This problem needs to be taken much more seriously. All towns need to fund solutions,” said another.

Many respondents described the debilitating effects of tick-borne illness and more than a few expressed a growing fear of going outdoors.

“We no longer take hikes in the woods, the state forest and some beaches,” wrote one resident. “Even though we live a mile outside of town, we have a serious deer problem in the neighborhood and we pick ticks off of ourselves and our dog daily just by staying in our yard.”

“It is the single thing in my view that keeps the Vineyard from being perfect,” another wrote. “You cannot really go to certain places on the Island without seriously worrying about getting a horrible illness.”

Many who said they favored “significantly reducing the deer herd on Martha’s Vineyard” had comments and questions about what “significantly” meant and how it might be accomplished.

“I answered ‘yes’ but with the caveat that a very carefully vetted analysis be done by qualified scientists as to the number of deer which could be safely culled so as to not permanently degrade the viability of deer on the Island,” wrote one respondent.

“As a last option because I realize that the ticks also get Lyme from other places too,” wrote another. “We need to consider the mice and other rodents. I would also want to make sure the deer meat to be used to feed people and not to be wasted if we hired professional hunters.”

Many said priority should be given to eliminating white-footed mice, and several mentioned research under way at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to genetically modify mice to make them disease-resistant. A few were concerned about any use of chemicals in eradicating ticks.

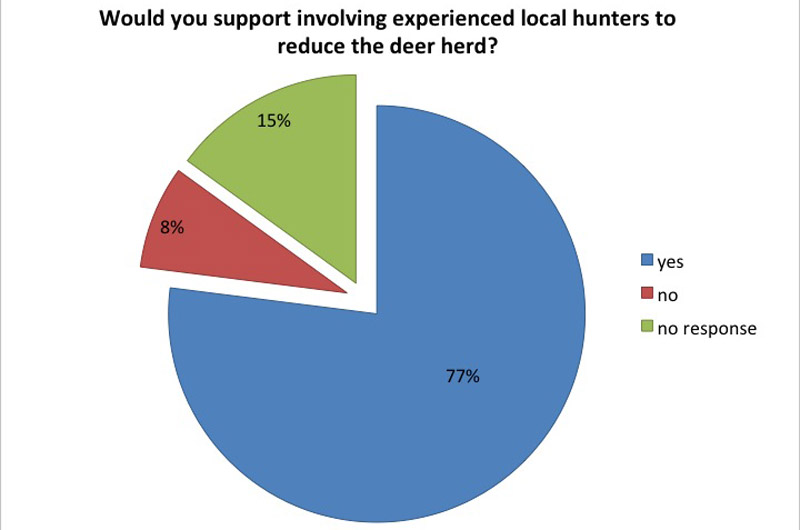

In response to a followup question, 77 per cent of those who supported culling the deer herd said they would support involving experienced local hunters to do so. Many respondents wanted to be assured that the venison would be used for food and not wasted.

Of the 1,311 respondents, 50 identified themselves as hunters. Three-quarters of these said either they or a family member had contracted a tick-borne illness and 80 per cent said they would favor significantly reducing the deer herd.

Comments (30)

Comments

Comment policy »