Ward Just, as the old newspaper saying goes, has ink in his veins. His grandfather, Frank H. Just was editor and publisher of the Waukegan News-Sun from the early 1900s until his death in 1952, at which time Ward’s father took it over.

Ward was born in 1935, and as a young boy he would bicycle down to the newspaper plant, located just a few blocks from his house, to visit his grandfather and to hang around with the pressman. He was fascinated by the Linotype machines and desperate for someone to teach him how to run them.

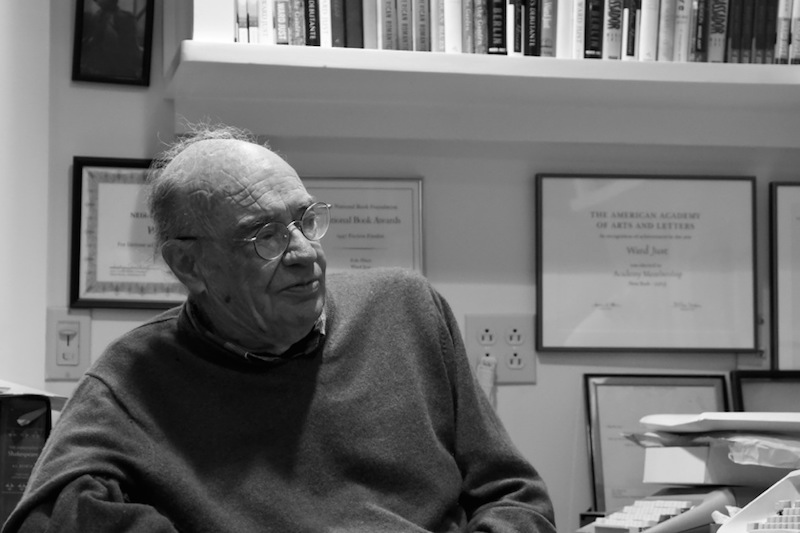

“But I couldn’t get any of those guys to teach me how to do that,” he said on a recent morning at his house in Vineyard Haven. “I think they had the fear that if I got it and I really liked it, I’d take their job.”

Such was the cross to bear for the publisher’s grandson.

In his new novel, The Eastern Shore, Mr. Just, 81, turns his attention and his memory to the subject of newspapers. His protagonist, Ned Ayres, begins working at a small Midwestern daily right after high school and eventually moves up the ladder to larger dailies in Chicago and finally to Washington, D.C., where he becomes editor in chief at one of the largest newspapers in the country.

The book is not an autobiography, but as with all of Mr. Just’s novels, it is fun to examine the parallel lines and periodic points of intersection. For example, Mr. Just also became a cub reporter at age 17, under the leadership of his father, Frank W. Just. He would go on to work as a reporter for Newsweek and then The Washington Post, for the legendary editor Ben Bradlee.

But a novel by Mr. Just never hews too closely to his real life, and besides, the pulse of the narrative does not rise and fall with the movement of the plot. Rather, it is the mood and tone of memory that propels the momentum, complete with all its myriad twists and turns, forward and backward through time.

In a passage early in the book, Ned Ayres returns to his home town for a visit. All his relatives are now dead and the homecoming mostly takes place at the cemetery. He remembers the nursing home where his mother and uncle lived and died.

He paused on the way out of town, pulling off the road in order to look again at the nursing home high on its hill, gradually disappearing piece by piece in the gathering darkness. In that aqueous light the Everett had the aspect of a prison long abandoned, lifeless, diminishing as he looked at it. Why had he come here? There was nothing for him in Herman. Herman represented past time and Ned Ayres had always looked to the future, tomorrow’s newspaper, the promise of things. But this was the future, wasn’t it? This wasn’t yesterday. It was tomorrow. His throat filled up. Shadows embraced the Everett until it was lost to view.

The passage could be held up as a metaphor for the book as a whole, which is both an homage and an elegy to the newspaper business. Mr. Just acknowledges that there is a sadness to the book.

“Yes, I’m afraid so,” he said. “I always looked on the newspaper business as a culture all its own. A culture that drew the most eccentric people, just strange birds. They were characters in a way you wouldn’t find in a brokerage firm or a bank or an automobile company. You would find them everywhere, of course, but not to the degree you would find them in the newspaper business. I always found that exhilarating.”

In 1970, when his father died, Mr. Just was asked to come back as publisher of the Waukegan News-Sun. But by this time journalism was in the rear view mirror. He had successfully made the transition to being an author, having already published a Viet Nam memoir and a novel. But because it was the family business, he gave it a try, flying home from Washington every month to attend to the business of the paper. But it was not for him. After a year, he passed the reins to his father’s assistant, and returned to a long and successful career writing novels. He was nominated for a National Book Award in 1997 for Echo House, and nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 2005 for An Unfinished Season. The Eastern Shore is his 19th book.

In 1982 the family sold the paper to Copley Press, which ran it for about 20 years before the paper folded completely — the fate now of many newspapers.

“It was the beginning of the internet and the distant early warning signs, sort of like the rustle of leaves in the trees,” Mr. Just said. “All of a sudden the classified advertising began to fall off a cliff, and that had been hugely profitable and there was nothing to replace it. And so all over the country publishers were saying, where do we go to recoup? But there was no place to go, and so it all began to dwindle. And all of these papers all over the country began to fold up.”

Ned Ayres experiences this funeral march on a day-to-day level, because unlike Mr. Just he never left the newspaper business. It was his whole life, as one passage from the book clearly establishes.

His life was orderly for the most part, seven-day weeks, twelve-hour days. He believed himself in charge of an alternate universe that demanded his full-time attention. His personal life, such as it was, did not interfere. In its own way editing was soul work, a deeply mysterious business. Page one, properly designed, was often a work of art, the lead story under a three-column headline and over a two-column explainer, news analysis, a photograph above the fold. The paper was fresh each day, a kind of miracle.

But by the end of the book Ned has been edged out, the newspaper business changing in ways he never could have imagined.

“He’s family-less and married to a business that is dying,” Mr. Just said. “It’s like watching your wife waste away. That’s kind of what happens to him.”

Mr. Just pauses and reaches for another Camel cigarette, his third in the course of an hour. He has been smoking for a long time. No reason to stop now.

“Everybody smoked when I was growing up, and in my profession it was part of the deal,” he said.

But despite being set during the golden age of newspapers and their decline, The Eastern Shore is not merely a sad book. By the end of the story, when Ned Ayres has retired to the eastern shore of Maryland, living alone in an old, crumbling manor house , the mood, oddly enough, shifts. After all, Ned has led the life he always wanted to live, and who could ask for more. Again, the compass points back to Mr. Just.

Mr. Just is not a lonely man like Ned Ayres. He has lived full-time on the Vineyard since 1992 with his wife of 33 years, Sarah Catchpole (their anniversary is Nov. 25), and he has two daughters and a son. But he is also a man who at a very young age knew what he wanted to do and for his entire life has done nothing else.

“Lucky is the person who really discovers what they want to do and they have the means to go ahead and do it,” he said. “So I’ve led a very fortunate life.”

He also has some advice for the newspaper industry.

“I think somewhere in life, to find a really well-written story that you’ve never read before, I think that’s still a terrific draw. And so instead of newspapers tinkering around the edges, go to the heart of the matter. And the heart of the matter is a really well-written story. That’s what you care about. A good story. Just a really good story.”

Which brings us back again to The Eastern Shore. It’s a really good story.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »