As efforts to reduce tick-borne illness on Martha’s Vineyard press forward, Island hunters this year are targeting both deer and ticks.

Island tick biologist Richard Johnson is working with landowners in Chilmark and West Tisbury who have agreed to provide hunting access to their land, adding perhaps 90 acres to the Island’s relatively scarce hunting grounds. It is the first step in a long-term initiative to reduce the incidence of tick-borne illness on the Vineyard by targeting deer, which provide food and habitat for ticks at a key stage in their life cycle.

Over the few years, Mr. Johnson hopes to eliminate enough deer to interrupt the disease transmission cycle. But reaching that goal will require widespread cooperation between hunters and property owners, and a better understanding of the resident deer population.

“It’s never been done on this scale,” Mr. Johnson said of the efforts. “It’s going to be absolutely a learning experience.”

The annual two-week shotgun season opens Monday, followed by primitive firearms season from Dec. 12 to Dec. 31. Archery season opened Oct. 17 and ends Saturday.

The Vineyard has between 15 and 60 deer per square mile, depending on the location, more than most areas in the state. Mr. Johnson now hopes to reduce the number to about 8 or 10 per square mile, at least in residential areas, although similar efforts in the region have had mixed results.

“What they are proposing to do is a great start,” state deer and moose biologist David Stainbrook said this week. He noted the importance of widespread hunting access, in part because individual ticks spend their lives in small areas, and the Island is large enough (about 87 square miles) to harbor multiple deer ranges. Most of the open land on the Vineyard remains off limits to hunting, providing vast sanctuaries for both deer and ticks.

Already, a number of archers have made use of the newly-opened properties, although some hunters doubted whether the deer-reduction goals were realistic.

“You are never going to reach that goal, no matter what you do,” said Brian Welch, a longtime hunter who Mr. Johnson has set up with a family that owns property up-Island. “There’s just too many people who don’t like hunting, the woods are way too dense.” He said the only way to achieve such drastic reductions would be through unlimited access to all properties to skilled hunters with shotguns.

Former Chilmark police chief and longtime hunter Tim Rich, who is also working with property owners up-Island, said white-footed mice are the primary hosts for Lyme disease, and he questioned the approach of targeting the deer. But as with Mr. Welch, he highlighted the value of deer management in reducing car collisions and property damage, along with putting at least a dent in the tick population.

“Some years all the deer you harvest are completely loaded with ticks,” Mr. Rich said. “Some years there are none.”

The Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, which oversees deer management in the state, sets a goal of between 12 and 18 deer per square mile, in order to protect forests and preserve habitat. Mr. Stainbrook said the goal could be realistic for the Vineyard, but he agreed that further reductions to affect tick numbers would be a challenge.

Several years ago, the state began offering virtually unlimited hunting permits on the Vineyard and Nantucket, where deer numbers are especially high, and allowing hunters to kill as many antlerless deer in a season as they like. Experts agree the changes have likely had some effect, but not nearly enough. (Many more females are killed each year, however, which helps control birth rates.) More important, Mr. Stainbrook said, is the need to open up private lands where the deer find safety.

But that’s easier said than done. Mr. Welch said he has already run into at least one territorial dispute, discovering a tree stand just 40 yards from his own on private property. “They don’t hunt as discreetly as I do,” he said of the newcomers, “and now they have made all the deer nocturnal.” He added that many hunters aren’t skilled enough to kill a deer on the first shot, allowing injured animals to escape. Depending on the size of the property, he said, access should be limited to one hunter. He also believes the hunters should be required to demonstrate their shooting skills to the landowner.

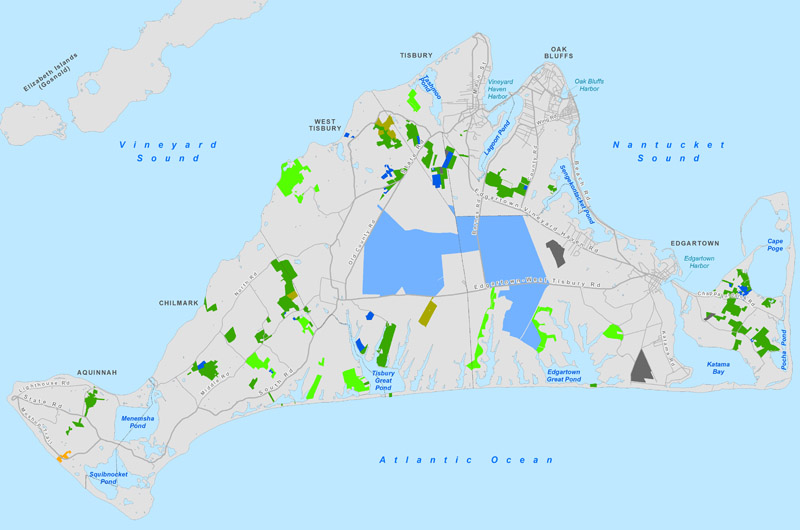

The Vineyard’s characteristic low-density housing, especially up-Island, creates perhaps the biggest obstacle, since hunting is prohibited within 500 feet of occupied dwellings, and within 150 feet of paved roads. That places more than three quarters of all public and private land on the Vineyard within the no-hunting setbacks.

“That’s a huge issue,” Mr. Johnson said, noting that a circle with a 500-foot radius covers about 18 acres.

The amount of forested land within the setbacks on the Island ranges from about 65 per cent in Edgartown (which has the largest portion of the state forest) to 90 per cent both in Tisbury and Oak Bluffs. Even in Chilmark and Aquinnah, considered the most rural towns on the Island, the figures are 78 and 83 per cent, respectively. West Tisbury’s portion is 72 per cent.

State bills seeking to either reduce or increase the setback distance for roads have all failed, Mr. Stainbrook said, although individual property owners may allow hunting near their houses. “That’s the route we need to take here,” he said.

In general, private property is considered open to hunting unless posted otherwise. But many landowners post their property before hunting season. Additionally, Chilmark and West Tisbury require written permission from the landowner or occupant for the discharge of firearms.

Mr. Rich said some landowners were concerned about legal repercussions of opening their property to hunting, although he said state law frees them from liability if they provide access free of charge. Once he explained that to landowners, he said, they were more willing to give written permission. Many properties were hunted in the past, he added, which also warmed people to the idea.

Years ago, many Islanders rallied to get landowners to ban hunting, including in Chilmark, but Mr. Rich said the growing awareness of Lyme disease and other deer problems has helped turn the tide.

Edgartown health agent Matt Poole, who has helped lead the Island’s tick-borne illness reduction initiative beginning in 2010, noted “moderate support” for deer reduction on the Island, which he attributed in part to education and outreach over the years. (A Gazette poll this year showed strong support for reducing the deer herd, and also strong support for tick tubes to target white-footed mice.)

Funding for the Island initiative comes to an end this year, and its future, including the deer reduction efforts, remains unclear. Island boards of health, which oversee the program, have about $10,000 in remainder funds to continue the work next year. They plan to seek additional contributions from Island towns next year, along with state, federal and private funds. Mr. Poole and Mr. Johnson both emphasized the importance of private donations, which can be made payable to the town of Edgartown.

Looking ahead, Mr. Johnson said he hoped to expand the program next year with more land, and to establish a more formal process for evaluating properties. He also hoped to get more young people involved, since maintaining the desired herd size would be a long-term effort. Mr. Johnson is now working with the state to develop a population model that will help determine a clearer reduction goal.

Meanwhile, Island boards of health hope to continue their usual outreach and education, along with conventional control measures such as the private yard surveys that Mr. Johnson has been conducting on Chappaquiddick and in Chilmark.

“If we don’t cause an additional deer to be harvested, there is still a lot of work that needs to be done and should continue,” Mr. Poole said.

Comments (12)

Comments

Comment policy »