What you have lighted upon, curious reader, is a nest of memory built twig by twig of fact-checked and emotional truths fertilized by nesty things like author’s privilege, the bird’s eye view of history, and the unflappable flight of time betwixt this writer’s second reading of Jane Eyre, which is most assuredly, most compellingly, happening now, and the first.

Where and when we unclose the door to a sixth grade classroom in Oakland, Calif., circa 1970s, where six bell-bottomed girls of a feather roost together reading Jane Eyre for extra credit. All, of whom I am one, are in their 11th year, in an era when 11 was closer to 10 than eleventeen. A time of Miss Ingram, not Instagram and error codes.

Like other literary BFF’s — Eloise, Alice, Nancy, Laura, Anne — Jane had captured our very souls and we committed that spring to understanding what moments we could of her Victorianized broderie without knowing she would be our gateway read to the other Alice who inhabited a different kind of wonderland in Go Ask Alice, and to Plath’s jarred star pivoting in a moonless universe. Harry was not even a quidditch of the imagination yet, and besides a boy!

Found and yet confounded, lost in a thicket of words, we formed the Jane Eyre Support Group. We were inspired by our mothers, hoop-earringed and platform shoed, some of whom we called by first name, at their request, instead of “mom,” who were disappearing into women-only support groups. If it worked for them, why not us?

But it only worked for mom until it didn’t for dad, and that’s a different story ending in unmarriage, and the ceremonial liberation of “r” from “Mrs.” Steinem-style. Still, we picked up on what they threw down: vibes of solidarity and sisterhood sealed with tokens of sensimilla, the de rigueur cannabis sativa of that time and place when we flocked to the un-Mary Jane.

We winged round the succulented highlands of Lakeshire, deconstructing and re-reconstructing Jane. Eyre, not Austen, to be most clear. We read passages silently and then aloud. Listening. Questioning. Twittering, like girls do. Agonizing, like girls do. We navigated sentences feathering forth like swollen spring rivers, only to slip on engraved riverstones of words without conquering meaning in toto.

I want so to remember that the Jane Eyre Support Group employed the Ouija board. But that would be a misflap of memory, as I am corrected, via text, by another member of the group who reminds me that it was not until the following year, with a semester of world history beneath our macrame belts, that we Ouija’d Henry VIII’s second wife, Anne Boleyn, a top-10, 16th-century strategist of the heart, before she lost her head. O, Reader! Sooner is better to confess: the Jane Eyre Support Group was self-supporting. Orphaned. We were sans teacher or other adult, desperately seeking a proto-Lena Dunham, an older sister who we perceived through inexperienced eyes, most practiced in pre-teen passages: lipstick, Kotex and kissing a la française. Alas, no surrogate Mother hen clucked us to her and we peeped around like excitable lost chicks.

And so, alone together, we capered along with Jane, understanding enough to keep reading because I think, in retrospect, we each sensed within, or wished for, a measure of her fortitude and forthrightness. The Viet Nam War was over, but Pax Americana existed only in bumper stickers of white doves and peace signs. Seemingly everyone was revolutionizing away from organized religion and traditional gender roles, and in this widening web of cultural unambrosia, we bookmarked Jane, our secret Victorian role model, whose comportment inspired our own movement toward selfhood.

The end is now closer than the beginning. As readers, as devotees, we trailed Jane away from and then back to the charred remains of Thornfield and onward to Ferndean, where our mixed-species lovebirds were reunited and, like a pair of quill-fated phoenix, rose up from the moss and moor of nearly 700 pages in a triumph of the heart. And with the first words of the final chapter, “Reader, I married him,” we readied to fledge our pledge, and the Jane Eyre Support Group was nevermore.

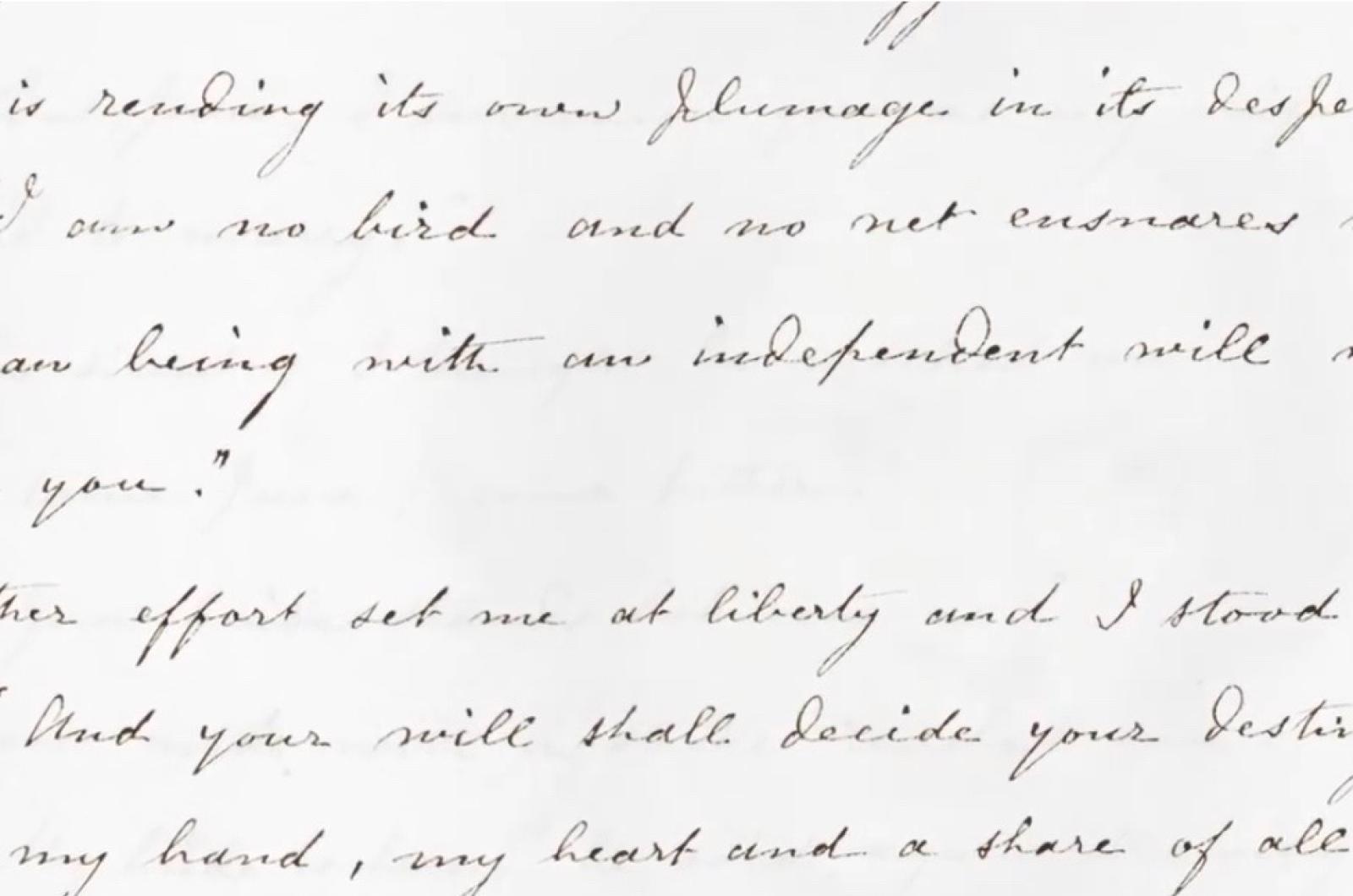

Upon which, I up and flew to London for summer vacation, where the curtain undraws on me perched above longhand Jane, the original manuscript under glass, in the British Museum (now housed at the British Library and, for the first time on American shores, temporarily Brexited at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York city).

My father is at my side — paisley-shirted, bearded, aviator-glassed — perhaps feeling the momentousness of this moment and maybe envious of my young girl heart surrendering to something bigger than myself.

I bow my head and visually trace Charlotte’s practiced letterforms, which later as a designer I would label as ascender, descender, bowl, counter, and x-height, as easily as naming body parts. My being, wholly and unapologetically understanding the necessity of placing pen to paper, of finding refuge in the secret fold of words, of creating an acceptable means for a girl to remain physically present, but mentally and emotionally safeguarded.

And now so may you too, faithful reader, whom I beseech to tarry not in migrating, singulaire or en masse, to the Morgan Library & Museum, where your 21st-century self (perhaps now middle-marched or otherwise) may swoon over these very pages, for there was and is only this one ‘fair copy’ manuscript that hatched Jane Eyre and uncaged the words: “I am no bird; and no net ensnares me.”

The exhibit, Charlotte Brontë: An Independent Will, continues at The Morgan Library & Museum in New York city, through Jan. 2, 2017. The centerpiece of the exhibit is a portion of the original manuscript of Jane Eyre, on loan from the British Library.

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »