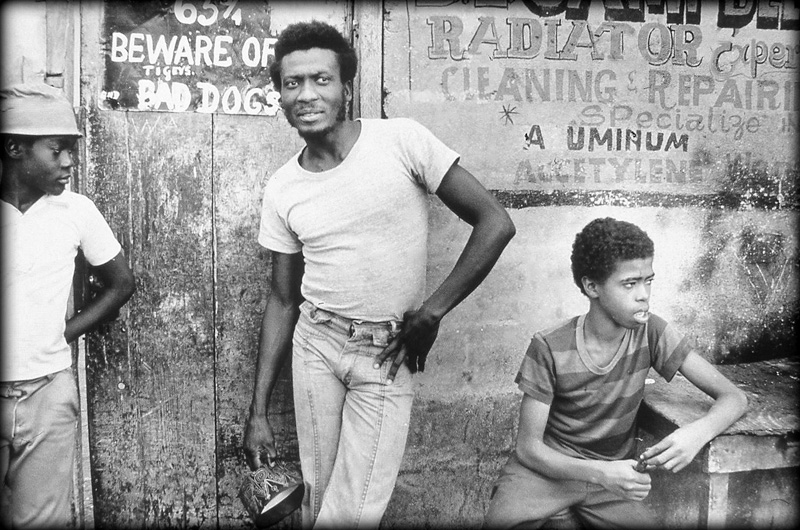

As April Fool’s Day came and went recently, I remembered that Jimmy Cliff was born on that day in 1948. I had the privilege of photographing both Jimmy and Bob Marley for the New York Times in the fall of 1975, heralding the “invasion” of the beloved heartbeat of reggae music to our shores. Oddly enough, I considered Jimmy Cliff the bigger star at the time, having attended the groundbreaking movie, The Harder They Come, many times at the Orson Wells Cinema in Cambridge. That movie transformed my life. I found I had a new passion. I couldn’t get enough of the patois, the visuals, the sounds and culture that was Jamaica.

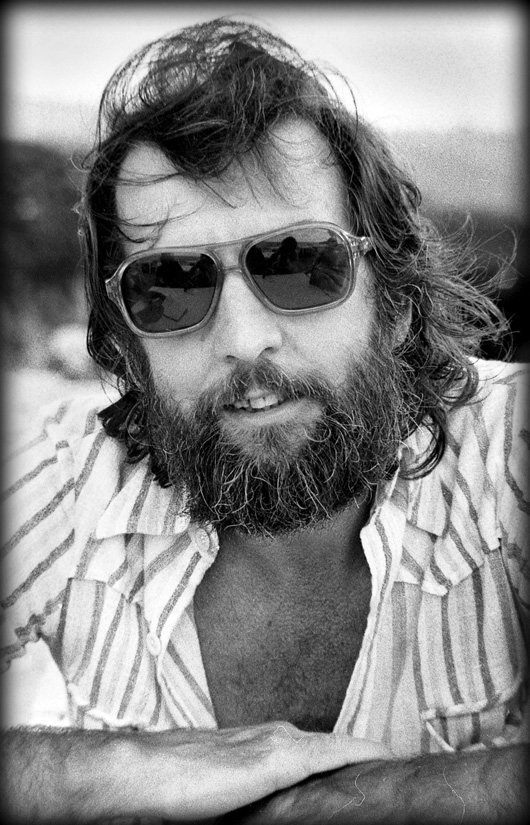

The photographs and article in the New York Times (written by my best friend and creative collaborator, Stephen Davis) led us to a book deal with Doubleday that became Reggae Bloodlines, published in 1977. One of our major goals while doing our research in Jamaica was to meet the director of The Harder They Come, Perry Henzell. We met up with him at his home along Jamaica’s glorious north coast. He was gracious and humble, and didn’t seem to realize the influence his movie had among the student population.

The soundtrack to that movie became the soundtrack of our lives. I took photos of Perry along with his wife, Sally, and their young children, Justine and Jason. It all felt uncommonly familial.

Flash forward some 30 years to when Tamara Weiss, former owner of Midnight Farm, stopped me in downtown Vineyard Haven and told me she had just returned from Jamaica where she stayed at place called Jakes, located on the south shore on Treasure Beach.

“You have to go immediately,” she said. “They remember you from the ‘70s!”

“They” were the Henzell family who owned and operated Jakes. Perry and Sally had founded the rustic resort in 1993, and Sally has been its matriarch since Perry died in 2006.

And so in the winter of 2007 I took a pilgrimage to Jamaica with my son Willie and his close friend from the charter school, artist Dan VanLandingham. I was hard at work on my book The Reggae Scrapbook. Willie and Dan were my traveling Wilburys. After a week of touring the music studios of downtown Kingston, we headed for the south shore.

Treasure Beach is not the tourist destination that people conjure when they think of Jamaica. It’s no Negril, Ocho Rios or Montego Bay. It’s quirky, laid back and fairly isolated. You almost need a four-wheel drive to navigate the potholed, pockmarked roads just to get there. Oddly enough, the road reminded me of any number of such patchwork roads we encounter up Island, like the road to Stonewall Beach or the Menemsha Inn road. The whole area is only about a mile or two long with a series of bed and breakfasts, funky bars and local eateries.

We stayed at Jakes for four nights, and it did not disappoint. I reacquainted myself with Sally Henzell, who gave us the royal treatment. We both mourned the loss of Perry, a gentle, creative soul who died at 70 of multiple myeloma.

On that trip, I also introduced Willie and Dan to reggae as it was meant to be experienced in Jamaica. We attended an annual 24-hour reggae marathon concert called the Rebel Salute (20,000 were in attendance). I finally went to sleep at dawn, down under the stage, curled in a fetal position, clutching my camera for dear life as the bands played on.

Flash forward another 10 years. My son Willie had fallen in love with a Jamaican woman. How could I resist revisiting that special gem of ocean and post hippie culture? I made arrangements this past March to travel back there with my wife Ronni, along with Willie and his girlfriend. Jakes still held a special place in my heart that will always be sacred.

During the final evening of our five-day retreat, I took a walk about half a mile down the crescent beach to a place called Calabash Bay where the local fishing industry coalesces to bring in the catches of the day. Fishing was once the main economy of Treasure Beach, but it is no longer what it used to be. Like the Vineyard, many have turned to community-based tourism to take visitors fishing and on tours to Pelican Bar, Black River Safari and the Galleon Beach fishing sanctuary. Once again, I was reminded of Menemsha. The salty, fishy water smell, the enthusiasm shown by the men who posed with their daily catches, and the glory of the simple life — one that was centuries old. Wifi reception and CNN feeds were transcended by the soothing sunset and rays of light being cascaded through wired up fishing crates. At night, it was fresh “red snappa” for dinner.

It was hard to say goodbye on the final morning, especially knowing that I might never make it back to Jamaica again. My sense of extended family with the Henzells and their staff had only deepened. I felt so grateful that I had wandered into the Orson Wells cinema so many years ago and let the spirit of that movie take me on the journey of a lifetime, meeting and greeting the people and culture that oozed from The Harder They Come.

You can get it if you really want, and I did. And then some.

Peter Simon, a photographer, author and longtime Gazette contributor, lives in Chilmark.

Comments (7)

Comments

Comment policy »