There is a good reason the Martha’s Vineyard Museum has far more shipwreck artifacts than it can display in its new exhibit Shipwrecks! Stories from Beneath the Sea, and far more stories than it can tell in its small exhibit space in Edgartown.

It’s because we have a lot of shipwrecks around here.

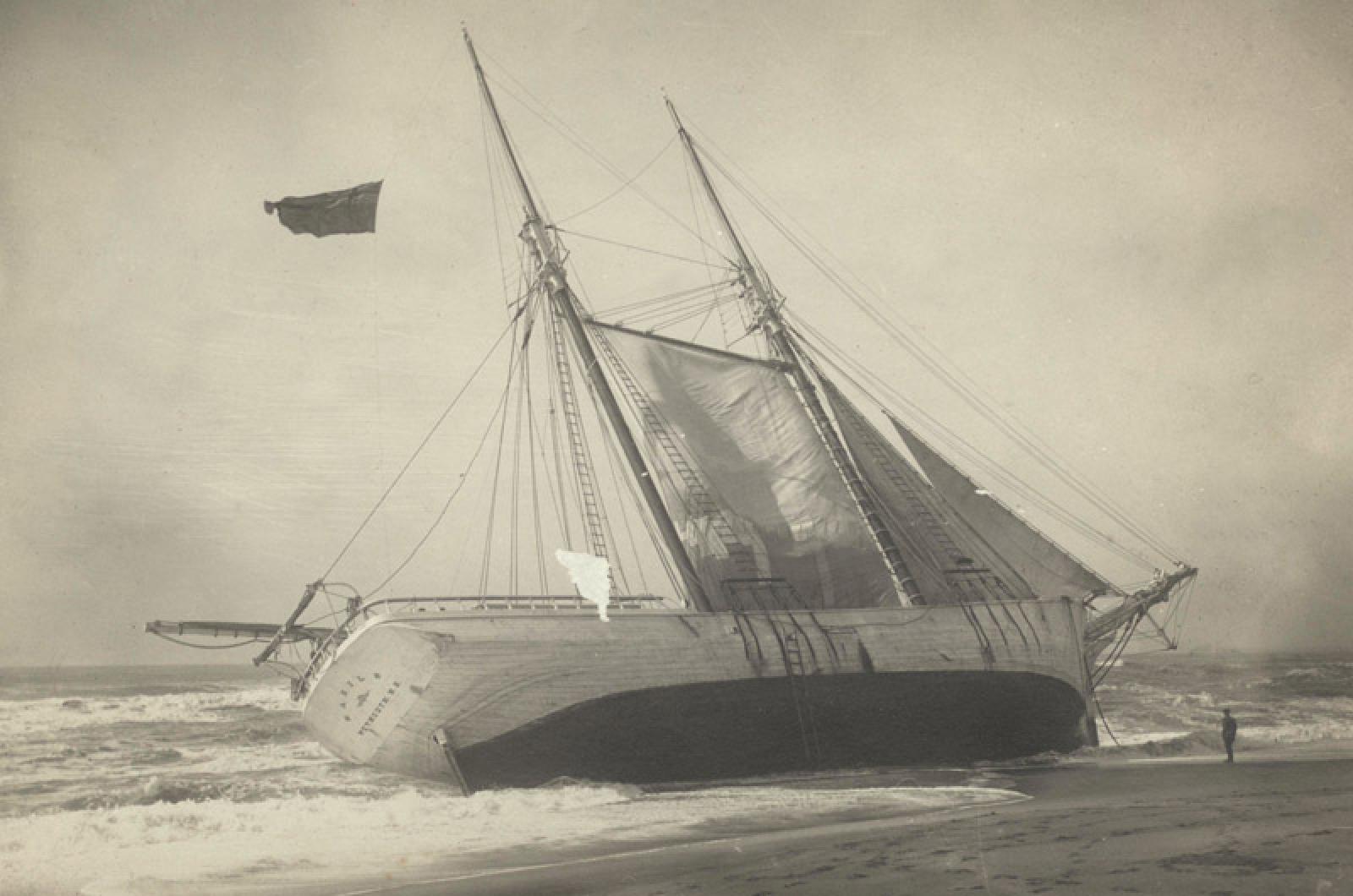

Take, for example a late September evening in 1898, with Vineyard Haven Harbor laden with cargo schooners laying safe between East Chop and West Chop. Or so they thought. A fierce gale lashed up, causing havoc in the harbor, with massive ships tossed ashore at the mercy of Mother Nature.

“From early morning until late at night the water about the port was strewn with wreckage, and vessels were constantly driven ashore, many of them to be dashed to pieces,” according to an account in the Gazette. “Twenty-one schooners, nearly all heavily laden, and one turkentine are ashore; four schooners now lying at anchor are totally dismasted; two others were sunk, and one bark is resting at the bottom, entirely submerged. It is known that at least ten men have perished, and it is very probable that as many more have lost their lives.”

A total of 63 ships were known lost in that single storm, a testament both to the fragility of seafaring life in those times, the inadequacy of weather forecasting in that era, and the incredibly busy and lucrative cargo industry that regularly plied Vineyard shores. Still, the Gale of 1898 is hardly a footnote on an updated map of local shipwrecks that is part of the new museum exhibit. The Island is ringed with legendary disasters at sea, and the exhibit shows only the ones we know most about.

“There’s something always compelling about disaster,” said Anna Barber, curator of exhibitions at the museum. “These huge giant vessels that feel like nothing could ever happen. Imagine being on it and everything is safe and secure, and then it all goes wrong.”

It is easy to imagine such a scenario while perusing the exhibit, with so many artifacts on display. There is a life jacket, apparently unused, from the City of Columbus, a 275-foot luxury cruise liner that went down off Aquinnah in 1884.

The City of Columbus disaster sent shock waves around the world. Until the Titanic sank in 1912, it was among the worst shipwrecks in history, with more than 100 lives lost. Newspapers of the day covered the story for years after the sinking, including the daring work of a volunteer rescue crew of mostly Wampanoag tribesmen.

There is a door from the Port Hunter, a supply ship loaded with goods for troops in Europe wrapping up World War I, which sank just off Oak Bluffs after a collision in the particularly bleak winter of 1918.

That wreck remains part of Vineyard lore to this day. No lives were lost, but many crates of cargo were salvaged by opportunistic Islanders. Some returned it to the U. S. government, some didn’t.

“Every house on the Vineyard of a certain age probably has candles,” Ms. Barber said. “Tens of thousands of candles washed up. All of a sudden it was a free for all with all this great stuff.”

Homeowners of the day made good use of the leg wrappings known as puttees, intended for the troops. They were sewn into blankets, shirts, even underwear, and known by the name of the wreck they came from.

“Oh, well, of course, everybody wore Port Hunters,” said Robert Chapman who is among the many voices in the oral history part of the exhibit. Mr. Chapman died in 2002. “God, I grew up wearing Port Hunters in the wintertime. Itchy itchies. It’s long underwear, is what it was, long underwear, long-sleeved tops and long-sleeved bottoms. But you called them Port Hunters. That’s where they came from. Everybody had Port Hunters. I had plenty of them. I wore them for many years. They were good, but, as I say, they were kind of itchy.”

The Port Hunter remains almost completely intact, resting in its watery graveyard about 65 feet below the surface of Nantucket Sound. It’s a popular site for recreational divers, though a bit treacherous with the swift currents. A video of the wreck, shot in remarkably clear water, is part of the exhibit.

Also part of the exhibit are sonar images of various shipwrecks around the Island, and the sonar unit used to make them. And later this summer, a number of noted experts will lecture as part of the exhibit, which will remain on display until next December. Among them is Vic Mastone, director and chief archaeologist of the Massachusetts Board of Underwater Archaeological Resources (Tuesday, June 27). He will speak on how shipwrecks can be used to study hurricanes and climate change.

Also scheduled is Arnie Carr, a Vineyard native and marine biologist (Friday, July 14.) He was among the first divers to extensively explore the wreck of the Port Hunter, and will lecture on what the shipwrecks still resting on the ocean floor can tell us about our marine history.

“It’s fascinating to look at how people navigated through here, what they knew, what they didn’t know,” Ms. Barber said. “Sometimes it raises a lot more questions than it answers, but history has a tendency to do that, I suppose, which is why it’s great to study it because you’re never going to come to the end of the road.”

The exhibit opened April 14 at the Martha's Vineyard Museum, 59 School street in Edgartown, and will continue until Dec. 23, 2017.

Comments

Comment policy »