About two hundred million years ago, exploding volcanoes between Nova Scotia and Brazil created an atmospheric furnace that wiped out more than three quarters of all animal life on Earth.

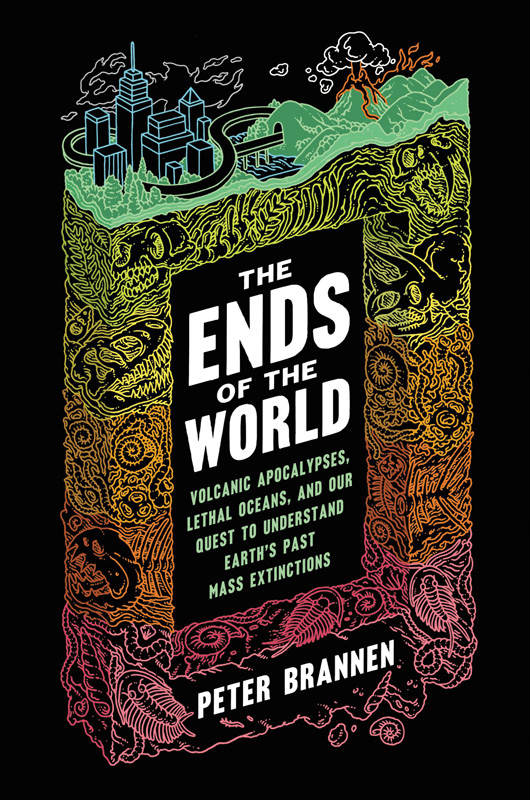

The catastrophic event should come as a wake-up call to our own species as we continue to alter the climate with fossil fuels, writes Peter Brannen, an award-winning journalist and former Gazette reporter, whose first book, The Ends of the World, comes out June 13.

The End-Triassic Extinction left its signature in the towering Palisades of New York, where oceans of magma had once risen through the Earth’s crust, spewing carbon dioxide and contributing to a period of intense global warming. Erosion eventually exposed the cooled magma seams, forming the iconic cliffs on the banks of the Hudson River.

It was here that Mr. Brannen began a two-year journey into the Earth’s geologic past, exploring six mass extinctions and what they might tell us about our own dangerous experiment on the planet’s oceans and climate.

The Ends of the World covers 445 million years of Earth history — from the deep-freeze that ended the Ordovician Period to the overhunting that likely killed off many of the large mammals in North America at the end of the Pleistocene. In most cases, Mr. Brannen writes, a global carbon cycle gone awry played a key role in planetary chaos.

The book also looks ahead to the possible consequences of human-caused climate change over thousands of years, and an inevitable planetary reset 800 million years in the future.

Mr. Brannen is among the featured authors in this year’s Martha’s Vineyard Book Festival in August. He also plans to speak about the book in Boston, New York and Washington D.C. in the near future.

After signing a publishing deal with Harper Collins in 2014, Mr. Brannen hit the road, exploring geologic sites in the United States, Mexico and Canada, beginning with the familiar Palisades.

“I thought it was so cool that there was this thing right next to New York city that ended the world and no one even knows about it,” he said this week at the Gazette office, where he worked from 2009 to 2012.

Over the next year or so, he crossed paths with renowned geologists, deep-time experts and fossil hunters, learning all he could about the most calamitous moments in the Earth’s history.

It was a steep learning curve, he said.

“I don’t even think trained geologists really can grapple with geologic time,” he said. “It’s one of those things like distances in space, where you just can’t wrap your head around it.”

Mr. Brannen incorporates various strategies in the book to help the reader visualize the enormity of the subject, he said. In one example, he uses the analogy of one human step being equivalent to 100 years of history. After one step backward, he writes, the Internet and electricity flicker out, two world wars are un-fought, and the Ottoman Empire reappears. All of civilization passes by before one can walk to the end of a city block.

To continue with this metaphor, arriving at the formation of the Earth would require walking 20 miles a day, every day for four years.

“Clearly the story of planet Earth is not the story of Homo sapiens,” he writes.

Unlike other books about mass extinctions, The Ends of the World serves as both an exploration of deep time and a warning about the unintended consequences of adding huge amounts of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere.

“The experiment we’re running today on our ocean and climate has been run before in Earth’s history and it doesn’t tend to end well,” Mr. Brannen said. “So we should really think twice before we start messing with these big geological forces.”

For a book about apocalyptic endings, The Ends of the World is surprisingly funny, capturing the relative absurdity of everyday concerns in the modern world, and the quirky brilliance of the people who devote their lives to studying the distant past (and future). “A lot of these researchers have a certain amount of gallows humor,” Mr. Brannen said.

“I don’t find it to be a depressing topic,” he added. “I think it’s just really interesting. . . . And I didn’t want to write a book that didn’t have my personality in it.”

After a year of research, Mr. Brannen took to cafes in Boston to hammer out the book, delivering a first draft last summer. Some of the writing also took place on the Vineyard, where his family has a home. “It almost felt like taking a crash PhD in a year in a half,” he said, noting that he could easily have spent 20 years on the subject.

“You interview these people who are PhDs and have been working on it forever,” he said. “They forgot why what they are doing is super interesting, and it takes an idiot like me to come in from the outside.”

His training at the Gazette came in handy, he said, recalling a drive through upstate New York when he spotted a glossy black outcropping on the roadside. He pulled off at an exit for SUNY Fredonia, walked into the geology department, and soon found himself talking to one of the world’s leading experts on shale rocks in the Devonian.

“Without having reporter experience for the Gazette, I would have been too scared to just walk into a random place and start asking people questions,” he said. He credited his work on the Vineyard, and also a fellowship in science journalism at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, as creating a foundation for his research.

“Most of these mass extinctions, or what we know about them, were what happened in the oceans, because that’s where more of the fossil record is,” he said. “So it is in a lot of ways a story about the Earth’s oceans.”

One challenge he ran up against in his research was a lack of communication among academics in different departments. “I had to talk to so many different people to get a big picture of what was going on,” he said. But he hoped the book would help bridge those divides. “I’m hoping even beyond just the general public that some of the paleontologists and geologists that are working on this stuff will find some things that they hadn’t really encountered before,” he said.

Mr. Brannen recently returned to his Island stomping grounds to write an article on the Gay Head Cliffs, where geologists have long studied the Cretaceous deposits and their clues to the past. The article will appear in the Martha’s Vineyard Magazine this summer.

One benefit of covering half a billion years of Earth history, he said, has been a new appreciation for his natural surroundings, even those close to home.

“I’d never look at a rock the same way again,” he said.

Peter Brannen will speak on Saturday, August 5 at 1:10 p.m. at the Harbor View Hotel, and on Sunday, August 6 at 1:15 p.m. at the Chilmark Community Center.

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »