Alexandra Fuller, the author of five books of nonfiction (including Don’t Let’s Go To the Dogs Tonight, Scribbling the Cat and Leaving Before the Rains), as well as 17 years’ worth of stories for National Geographic, grew up in Zimbabwe. Her parents were colonials; her father, a cattle rancher.

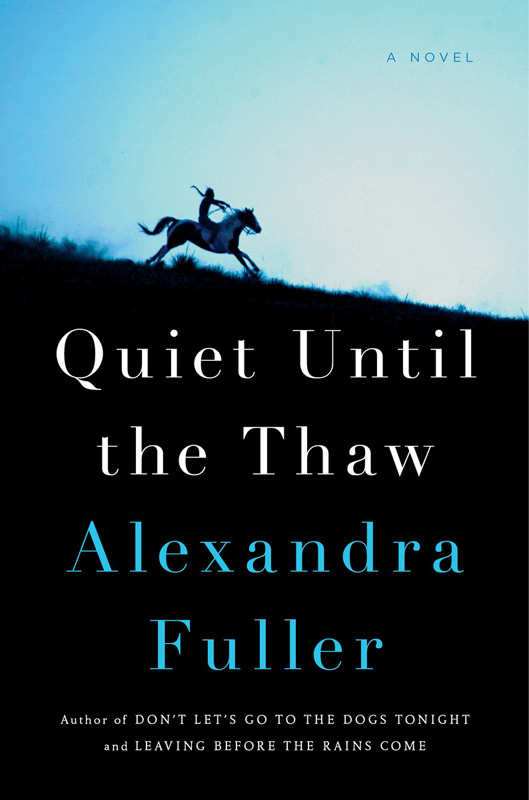

Nowadays, Ms. Fuller lives in a yurt in Wyoming. On June 27, she released her first novel, Quiet Until the Thaw. She will be speaking at 7 p.m. this Friday, July 7, at Bunch of Grapes bookstore in Vineyard Haven.

Ms. Fuller wrote her early books like the reporter she was and is — she tells it like she sees it, creating a warts and all family portrait that is hilariously funny, heartbreaking and horrifying. Her memoirs of Africa offer a strikingly honest view of her parents’ — and other colonials’ — racism.

Ms. Fuller’s newest work of fiction involves the Lakota people of South Dakota. She had visited the Pine Ridge reservation for a horseback ride, but ended up staying for three months. Quiet Until the Thaw is about two brothers, separated first by the Viet Nam war and then by one brother’s prison sentence. It is about not only the external violence that separates them, but the violence that takes root in the soul of people who are oppressed. In the end, the Pine Ridge reservation and what used to be called Rhodesia are pretty much the same place.

“The Rez and the people who lived there made sense to me on a blood and bone level,” she writes in the book’s introduction. “For the first time since coming to the United States in the mid-nineties, I neither needed to explain myself nor have this world explained to me.”

She arrived at Pine Ridge to find the reservation’s hardships — emotional violence, child neglect, bitter weather, lousy shelter, inadequate medical care and food — familiar, in every sense of the word. In a phone interview with the Gazette, Ms. Fuller said, “I honestly looked around the Rez and said, who am I to judge?”

She quotes a poem by Yolanda Pierce, Litany for Those Who Aren’t Ready for Healing: “Let us listen to the shattering glass and the purifying fires, for it is the language of the unheard.”

“There’s no such thing as the voiceless,” she adds. “Only the deliberately unheard. People don’t take that kind of action unless they’ve tried everything else. The shattering glass, the burning tire, that’s the background music of my life.”

“What helped me see racism here was the experience of being a white settler. I found it everywhere, among the liberal whites who acted like their privilege was a big accident, and then what you call racism, the people who are openly racist, who are actually white supremacists.”

Quiet Until the Thaw, however, is less focussed on the violence of the oppressors than the strength and beauty of the oppressed.

“I was raised by indigenous people. The women who bathed me and taught me how to be a parent myself were African. When my mother was in the hospital to give birth to her last child, I was 11, and I was alone. I would have literally been dead if not for people with whom I didn’t even share a language. So, if I have any legitimacy in telling this story at all, it’s because I have such respect for them. However much the family units are dismantled by violence, by the neglect of governments, wherever you see this in indigenous communities, you’ll see the community desperately trying to put a family back together. And we whites don’t do that.”

The reading on Friday will also include time for questions. As for writing advice, Ms. Fuller did not hesitate. “If someone asks me for advice on writing, I tell them, sit still and observe what disturbs you.”

Comments

Comment policy »