How did I get here? Richard Russo’s latest short story collection, Trajectory, takes up this question again and again, looking back over the lives of its characters to trace their journeys.

“Over the last decade or so, without even realizing it, I had begun to obsess about destiny, and thinking about how people’s lives turn out,” he said.

The author is especially preoccupied by what he describes as: “That moment in peoples’ lives when suddenly at age 50 or 60 or 65, they look at the trajectory of their lives and realize that they probably have not gone where they thought they would and are wondering why.”

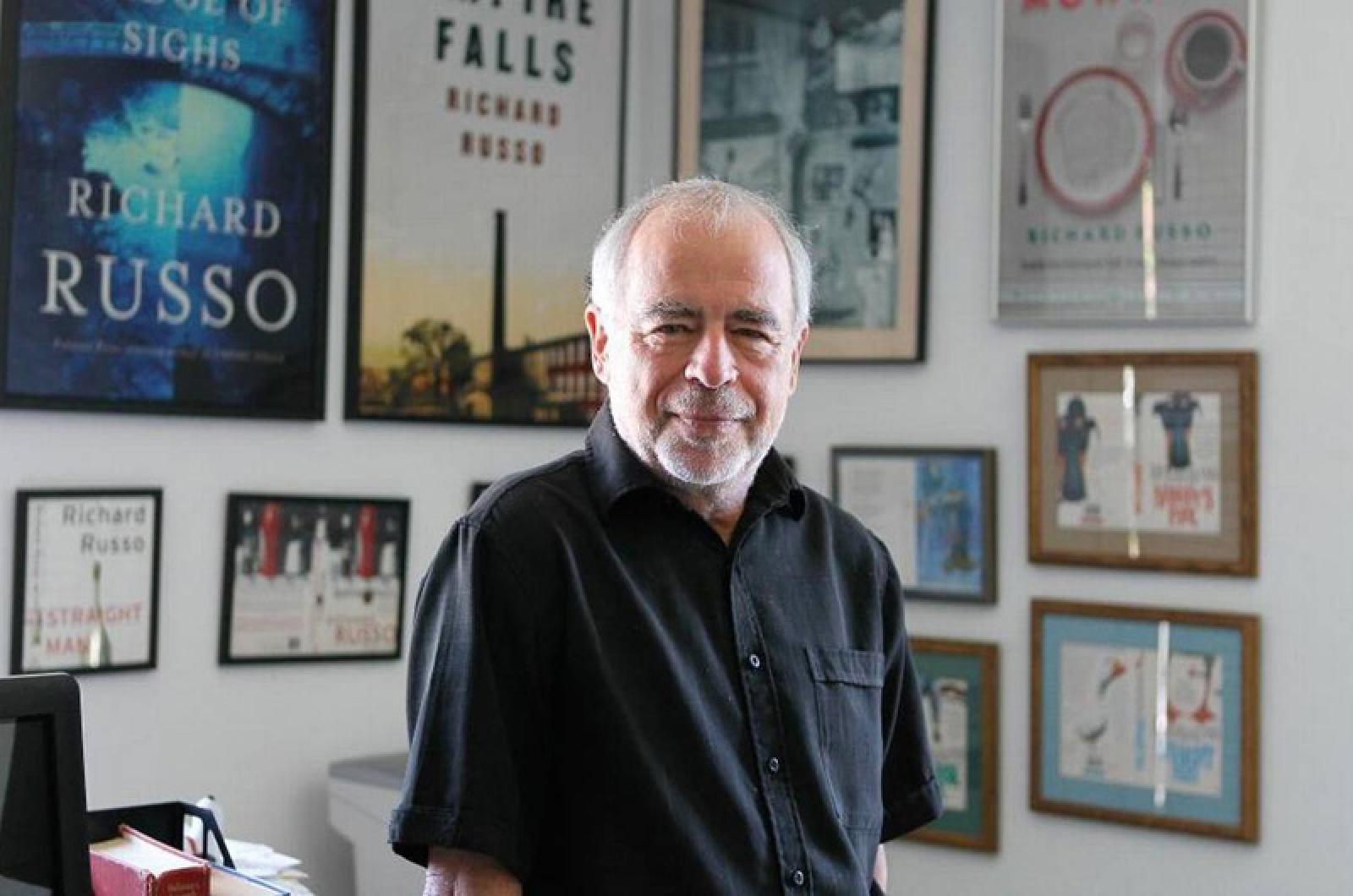

Mr. Russo wonders this himself. He spent his childhood in a small mill town in upstate New York, one of the first in his family to graduate from college and the only person in his family to pursue an artistic career.

“I don’t really think of myself as having made a lot of really great decisions in my life that have resulted in my having the kind of life that a writer dreams of,” he said. “Most of the best things that have happened to me in my life have been the result of pure dumb luck and sometimes stupidity.”

He offered his move to Arizona as a teenager by way of example. His mother had always dreamed of leaving the small town where she grew up and raised him.

“And so, with no money and an old, beat-up, beater of a car, the two of us, kind of at her direction, despite the fact that she didn’t drive, and I had only had my driver’s license for a matter of months, she decided we were going to move to Arizona,” he recalled.

They packed up a U-haul and headed west.

“I mean it was just the most ridiculous thing in the world to do. We were underfunded, we were underpowered, my mother had no job, she gave up a good job at General Electric, and it was just the most harebrained thing two people could have imagined doing at that time. And yet, almost everything good that has come to me in this life has been the result of that stupidity. At Arizona, I somehow or other grew to be a man and also a writer,” he said.

He continued: “It just strikes me as extremely unlikely that if I were to live life 99 more times, that anything like that scenario would ever happen again.”

Mr. Russo got lucky. Not all of his characters are so fortunate.

In the collection’s longest story, Voice, about a complicated relationship between two brothers exacerbated by their travels abroad, Mr. Russo writes of protagonist Nate’s “. . . secret fear that he’s led a life other than the one he was intended for, following the wrong trajectory entirely.”

In Intervention, a down-and-out woman looking to sell her home says to her real estate broker: “So now, for the first time, my whole life’s coming into focus. I’m fifty-seven years old, Ray, and every day I have to lie to myself just to keep going.”

Many of the stories take as their subject writing and literature. In Horseman, a professor criticizes a graduate student for not having a unique authorial voice. The story, in its self-referentiality, captures the spirit of Mr. Russo’s larger project, an attempt to understand life’s path, and by extension, ourselves.

“You figure out how to use the hammer, you figure out how to use the saw, you figure out how to use the drill. Right? Those are your tools. But at the end of the day, who is holding the hammer? You’re never really much of a writer until you can figure that out. And I think to a certain extent that’s true of life too, and it’s certainly true if you’re trying to figure out your trajectory, what your life has all been about . . . . Who are you?”

For his part, in both art and life, Mr. Russo seems to know who is holding the hammer.

Richard Russo will speak on Saturday at noon at the Harbor View Hotel, and on Sunday at 12:15 p.m. at the Chilmark Community Center.

Comments

Comment policy »