Max Eastman: A Life, by Christoph Irmscher, Yale University Press, 2017, Hardcover, 448 Pages, $29.

Indiana University English professor Christoph Irmscher’s new book, Max Eastman: A Life, crafts the biography of flamboyant 20th century writer, editor and longtime Vineyard fixture Max Eastman. At first glance it might seem like an odd follow-up to Irmscher’s excellent 2013 book Louis Agassiz: Creator of American Science, which told the life story of the Swiss-born Boston-based 19th century scientist now remembered mainly for his stubborn rejection of Darwinian evolution — if he’s remembered at all. But the two subjects are more alike than they seem: both were brilliant, both were difficult to love and yet much loved, and both have been largely and unjustly forgotten as the decades have gone by.

Max Eastman hasn’t had a comprehensive biography since William O’Neill’s The Last Romantic 40 years ago, and as with Louis Agassiz, Irmscher’s book is not only definitive but electrically readable. He has sifted through the sprawling, unpublished archive of Eastman papers at Indiana’s Lilly Library and Eastman-related papers at Harvard, and he has of course consulted the many books Eastman himself wrote, including his beguiling 1964 memoir, Love and Revolution: My Journey Through an Epoch.

The result is not only the kind of sly, knowing book Eastman loved to read but also the kind of book he loved to write: tough without being cruel, encyclopedic without being showy, and most of all sympathetic without being maudlin.

The book has a bursting, Rabelaisian story to tell. Eastman, who was born in Canandaigua , N.Y., in 1883, graduated from Williams College in 1905, was a teaching assistant at Columbia, and he became, as Irmscher puts it, “the Prince of Greenwich Village” while still very young. He edited two groundbreaking socialist magazines, first The Masses and then The Liberator, stood trial twice for his outspoken condemnation of America’s participation in the First World War, paid a prolonged visit to the Stalin’s Soviet Union at the height of the leadership’s tense vying with Eastman’s erstwhile hero Trotsky, and returned to the U.S in 1927 disillusioned with Stalinist socialism. He married his first wife, Ida Rauh, in 1911 and divorced her in 1922, married his second wife Eliena in 1924 and lived with her mostly at their idyllic house at Scitha Hill at Gay Head (now called Aquinnah, the old Wampanoag name), “shielded by scrubby trees, overlooking Menemsha Pond, and with access, albeit via a winding path and a now-crumbling boardwalk, to a private, pebbly beach.”

He was with Eliena virtually every moment during the weeks of her final illness in 1956. In 1958 he married his third wife, Yvette Szkely, but the three marriages were hardly the confines of his amorous activity — as Irmscher writes, “Max was loved by many women, and he loved many of them in return, not infrequently at the same time.”

And all the while, he was working: giving speeches and lectures, participating in debates, writing books, and, in a curious arrangement that held for most of his life, churning out articles for Reader’s Digest and its thuggish founder, Wallace (Wally) DeWitt, succinctly described by Irmscher as “relentless, direct, crude.” When DeWitt paid Eastman, he paid generously, and he gave Eastman a “roving editor” title and an expense account to go along with it. Eastman had considerable freedom and access to a readership that peaked at well over 70 million, but the irony of the country’s foremost ideological firebrand working for a publication whose founder reveled in its lowbrow pitch was never lost on Eastman. “His bank account was constantly overdrawn,” Irmscher writes at one point, “while the writing he really wanted to do was frequently interrupted by Reader’s Digest articles, which he could never be really sure would be accepted. He was afraid he was squandering his life.”

That same quaver of self doubt can be heard throughout Eastman’s life. Outwardly suave and confident, he inwardly felt a complex and constantly-shifting arrangements of doubts and insecurities that Irmscher treats with unfailing finesse, pointing out that this man, who commented on his own “interior revolt against intimacy,” could often alternate between “a yearning infant and a rebelling man, or maybe both at the same time.”

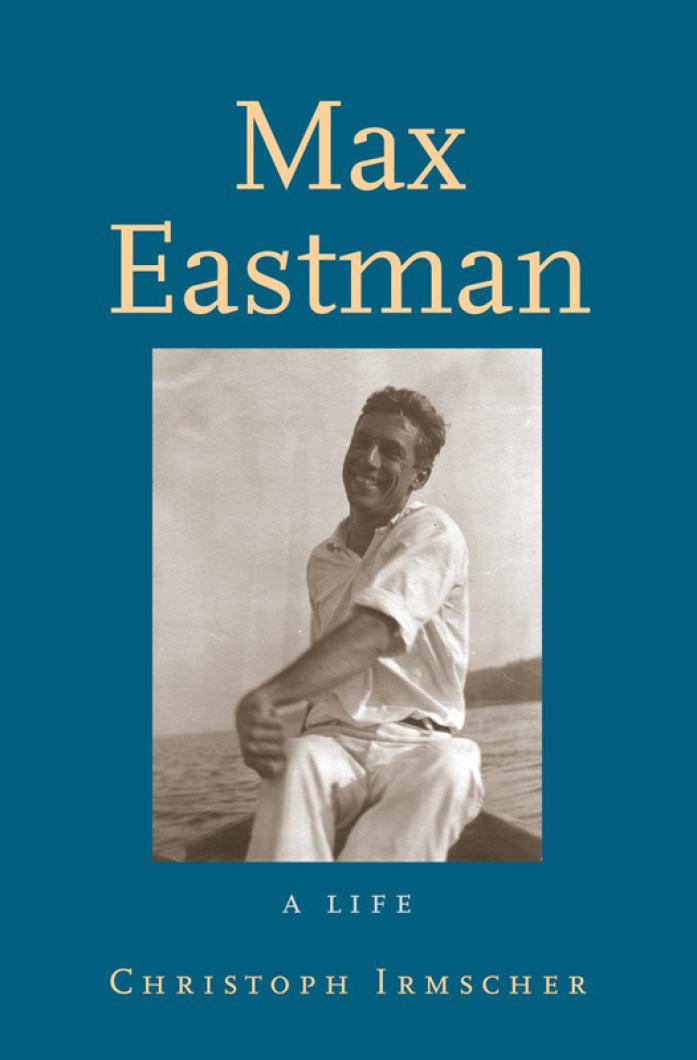

The Eastman evoked in these pages was physically beautiful for the whole length of his life, looking like “a cross between Hamlet and Lord Byron” when he was young but retaining a strikingly patrician air into old age, when friends and lovers still routinely reported “glowing thoughts of Max” to their diaries and letters, and when men and women alike were so startled by the sheer magnetism of the man that they couldn’t even dissimulate about it (in this sense the book’s cover photo, showing the author boating in 1909, is perfectly chosen). It was an easy magnificence not all the writers of his day enjoyed. Irmscher relates a 1946 encounter the Eastmans had in Cuba with Max’s longtime literary nemesis Ernest Hemingway: “Eliena couldn’t believe this fussy, ‘top-heavy,’ soft-spoken man with eyes as brown and expressionless as a beetle’s peering at her through steel-rimmed glasses was the same ‘blood-lusty he-man’ she had known in Paris,” Irmscher writes. “He looked like an overweight Englishman on vacation.”

As Irmscher notes simply, Eastman knew everybody, and everybody knew him. Virtually the whole of the early 20th century’s literary establishment makes an appearance at one point or another in the pages of Max Eastman: A Life, and one of the book’s many strengths is its clear-eyed assessment of Eastman’s own place in that establishment — especially important, since all of his many books have lapsed out of print, and even the faintest echoes of his literary reputation have faded completely. Knowing his subject’s mercurial combination of vanity and flinty realism, Irmscher never makes the mistake of over-praising the job-lots Eastman sometimes turned out for money, but he’s likewise keenly appreciative of the books that show Eastman’s talent (for instance, Irmscher refers to Eastman’s 1925 book Leon Trotsky: The Portrait of a Youth as “a peculiar work, marked by a quiet and largely unrecognized genius”).

None of it is enough to revive the subject, any more than Irmscher’s magnificent work on Agassiz could prop the titan back onto his pedestal. But for the length of a reading, Max Eastman: A Life brings readers inside a life lived full-tilt with passions and interests and doubts and bright Vineyard summers. If you had gone back to those days at the roaring start of the last century and asked Charlie Chaplin or Isadora Duncan or Max Perkins — or even a grudging Hemingway — who would among them would be getting a great biography in the 21st century, they would all have agreed: Max. And now he has one.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »