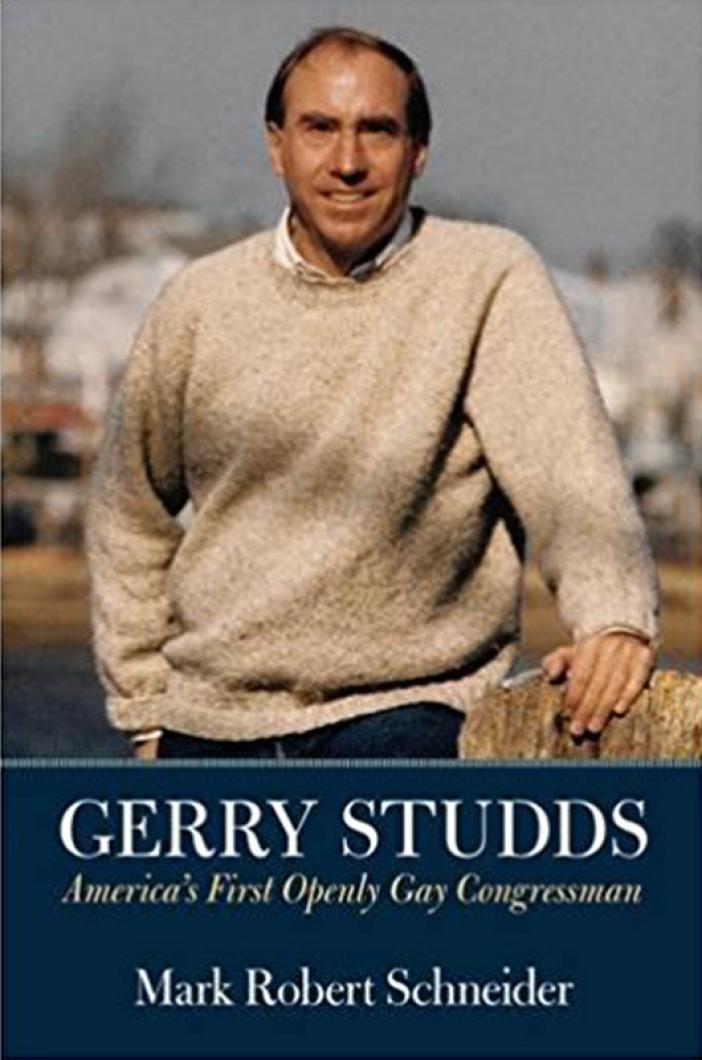

Gerry Studds: America’s First Openly Gay Congressman, by Mark Robert Schneider, University of Massachusetts Press, 2017.

Massachusetts Cong. Gerry Studds, the subject of Mark Robert Schneider’s tough and smart new biography, is remembered now in offhand conversation for a scandal. History — ably nudged along by Schneider’s book — will remember him for the long triumph that followed.

The scandal came in 1983, when Mr. Studds was censured by the House of Representatives for his sexual involvement with a 17-year-old Congressional page. In his address to the House, he admitted to bad judgment in the matter, and in the process became the first openly gay Congressman in American history, instantly joining the ranks of other trailblazers Mr. Schneider mentions, like Joseph Rainey and Jefferson Long, the first black congressmen, Jeanette Rankin, the first congresswoman, and Shirley Chisholm, the first African American congresswoman.

Mr. Studds made no cheap denials; he was clear from the beginning that his relationship with the page had been entirely and mutually consensual — no coercion, only a door left open to suspect it. The author, whose previous books include a winningly insightful biography of Mr. Studds’s colleague, South Boston Cong. Joe Moakley, gives the moment its full charge of complexity and at least partly subscribes to the impression contemporaries had at the time that the scandal and the censure darkened Mr. Studds’s attitude. Certainly Mr. Studds himself kept the whole event in crystal-clear perspective. Questioned about it years later by a debate opponent, he didn’t hesitate: “That’s the easiest question I’ve ever been asked,” he said. “It wasn’t anything that I’m proud of. It was a damn stupid and inappropriate thing to do, and I never said it wasn’t.”

It was a dark passage, the kind of very public indiscretion that could easily have ended a career, especially given its then still-taboo nature. But in the case of Gerry Studds, it was followed not by obscurity but by triumph: after his Congressional censure, after his public confession, Mr. Studds decided to run again for Congress, this time as both an openly gay man and an official who’d been censured. As Mr. Schneider laconically writes, “it took a certain amount of courage to do it.”

Mr. Studds won, and he was re-elected six times. He was embraced by the burgeoning gay rights movement and gladly became its standard bearer during the horrifying initial years of the AIDS epidemic. The widespread advent of the disease hit Mr. Studds personally; as his partner (and later husband, married one week after Massachusetts became the first state in the Union to make it legal) Dean Hara commented: “We went to funerals in those days the way other people went to weddings.”

A change seemed to be in the air with the 1993 election of President Bill Clinton, who’d promised on the campaign trail that he’d end anti-gay discrimination in the federal government. Mr. Studds endorsed him, telling his own constituents that Clinton’s views were “refreshing after twelve years and two presidents who were barely even able say ‘AIDS’ much less show a real commitment to battle it.” At the National Press Club inauguration party, Mr. Studds and Mr. Hara danced amidst a crowd of well-wishers. “This,” as Mr. Schneider puts it, “was no longer Ronald Reagan’s America.”

Boston Globe columnist David Nyhan wrote that the censure had permanently “eviscerated” Mr. Studds’s effectiveness as a Congressman on the national stage, but Mr. Schneider’s responding points have the greater ring of historical truth. Mr. Studds, he writes, “had been a national force for gay rights, for peace in Central America, and for the environment” — and many other issues could easily be added to the list, particularly the maritime and fishery issues that mattered so much to Massachusetts — and the state didn’t forget all this good work, as visitors to the Gerry Studds Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary can attest.

Gerry Studds died in October of 2006 after a lifetime of public service that saw great strides in gay legal and social equality and yet left much work still to do (his husband, for instance, wasn’t eligible for the pension provided to Congressional widowers and had to challenge this discrimination in court). And he lived in that public service long enough to sense a deeper change in the American political landscape, a coarsening that deeply bothered him, as he told a gathering at the Old Whaling Church in Edgartown. “It is increasingly difficult today to imagine sharing a laugh, a constructive exchange, or anything else remotely genuine with a political opponent,” he said. “Attack, distortion and demagoguery are now the tools of the trade.”

Most readers of this indispensable book will finish it thinking much the same thing — and wishing we had a whole lot more politicians like Gerry Studds.

Comments

Comment policy »