Katama Bay oyster farms have been closed for two weeks following three confirmed cases of Vibrio illness tied to oysters consumed from the area.

It is the first Vibrio-related closure in Massachusetts in the last two years, according to state Department of Marine Fisheries officials, reflecting increased measures to deal with the warm-water bacteria that first came on the scene about five years ago.

“Vibrio statewide is down, and even in Katama Bay is down,” state fisheries biologist Christopher Schillaci said this week.

The state Department of Health and Division of Marine Fisheries announced the closure last Friday, Sept. 29. Oysters cannot be harvested from the bay, which is home to a dozen thriving oyster farms, until before sunrise on Oct. 13.

Vibrio parahaemolyticus, also known as Vp, is a bacterial pathogen that naturally occurs in warmer waters. Consuming raw oysters with the bacteria can cause unpleasant gastrointestinal illness. Severe illness is rare and most likely to occur in people with weakened immune systems.

Cases of Vibrio began to rise in Massachusetts about five years ago. According to the Department of Marine Fisheries, in 2011 there were two reported Vibrio cases related to shellfish harvested in Massachusetts. That number rose to 33 in 2013, 11 in 2014 and 28 in 2015, before falling to 10 in 2016.

The trend was also seen in Katama Bay, the fourth most productive harvesting area in the state. Oyster farms in Katama were closed in September 2013, September 2014, and late August 2015 because of confirmed cases of Vibrio tied oysters harvested from the area.

Despite this year’s closure, Mr. Schillaci emphasized that Vibrio cases are on a downward trend. Stricter oyster harvesting and handling protocols have been instituted in the last few years during Vibrio season, which runs from June through October. Between the 2015 and 2016 seasons officials shortened the mandatory time between harvesting and icing from two hours to one hour and saw a significant reduction in cases, he said. “We’re still conducting research to refine and control and develop more area-specific control where needed,” he added.

Tests have shown that a particularly virulent strain of Vibrio has made its way to New England from the West Coast, Mr. Schillaci said.

“It was looking like a really good summer,” Edgartown shellfish constable Paul Bagnall said this week. But when he got home last Thursday after a day of spreading quahaugs, he got the call from state officials with the news that Katama Bay would shut down for two weeks.

Growing area closures are laid out in the state’s Vibrio control plan per the National Shellfish Sanitation Program. Closures are mandated when there are five illnesses in 30 days or two illnesses tied to oysters harvested on the same day.

This year Katama Bay met the latter criteria.

According to the state, the first oysters tied to the illness were harvested on Sept. 4 and Sept. 6 and consumed on Sept. 7. The second illness related to oysters harvested Sept. 12 and consumed on Sept. 15. A third case also involved oysters harvested Sept. 12 and consumed on Sept. 15.

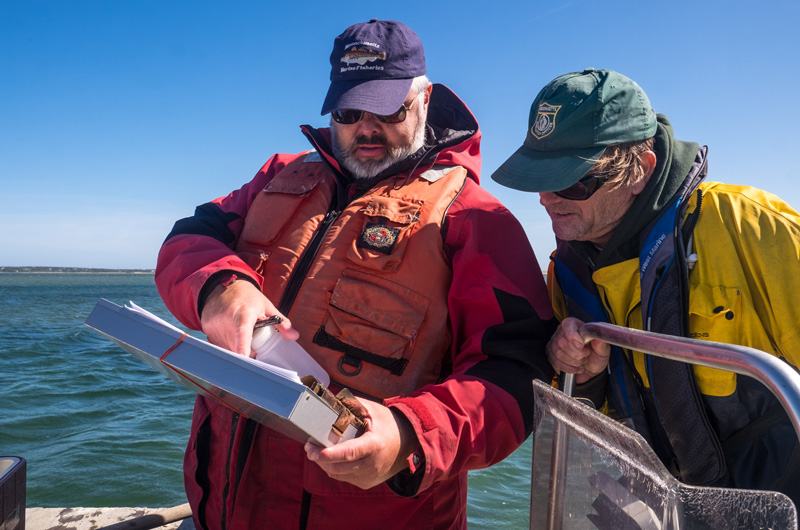

Oyster harvesters are required to keep logs about each harvest, and oysters are tagged with information including when and where they were harvested and put on ice. That tagging follows the oysters to wholesalers and ultimately to restaurants or fish markets. When Vibrio illnesses are reported, officials retrace the path back to when and where the shellfish was harvested.

Officials have declined to release the names of the harvesters. “We do conduct a thorough investigation from retail to individual harvesters,” Mr. Schillaci said. “We did not observe noncompliance.”

There is still potential for Vibrio when harvesters and dealers adhere to temperature or harvesting requirements, Mr. Schillaci said — the risk can be reduced, but may not be totally eliminated.

There can also be lag time between when illnesses are reported and the mandated closure, Mr. Bagnall said, the result of a reactionary closure. It takes time for information and testing to travel from the hospital to public health officials to the restaurant where the oyster was consumed and then to where the oyster was grown, he said.

“That takes awhile,” Mr. Bagnall said. “If the oyster is consumed off of Martha’s Vineyard, two to three weeks. If out of state, six weeks.”

Mr. Schillaci and others have been conducting ongoing research in Katama Bay and elsewhere to learn more about the bacteria, including whether testing can indicate when Vibrio is most present or most likely. In past years Edgartown shellfish farmers have discussed precautionary closures when the water is the warmest. Some shellfish farmers are also starting to move oysters out to Eel Pond, where the water is cooler and offshore oyster farming has taken root in the last few years.

The illness has been a source of frustration and concern for oyster farmers in Katama Bay and elsewhere. According to the Department of Marine fisheries, more than three million oysters were harvested in Edgartown in 2016, at a value of nearly $1.8 million.

Statewide oyster aquaculture is a $21.7 million industry.

Mr. Bagnall said Katama Bay oyster farmers are frustrated, but taking the closure in stride. He said the closure can hurt the dealers beyond the 14 days they are closed if wholesalers look to other sources. The oyster season usually runs through Christmas, Mr. Bagnall said. The closure will include the Columbus Day holiday weekend.

Oysters are increasingly popular and often consumed raw, Mr. Bagnall said, noting that there is no sell-by date as long as the oysters are iced. There is always a risk when consuming raw food, he said, but added that there is a high level of scrutiny over oyster industry.

“There’s a lot of oversight, and I don’t think people realize that when they’re slurping oysters down at the raw bar,” Mr. Bagnall said.

“The growers have really tightened up on their harvesting techniques,” he continued. “Katama Bay oysters are as safe as oysters can be.”

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »