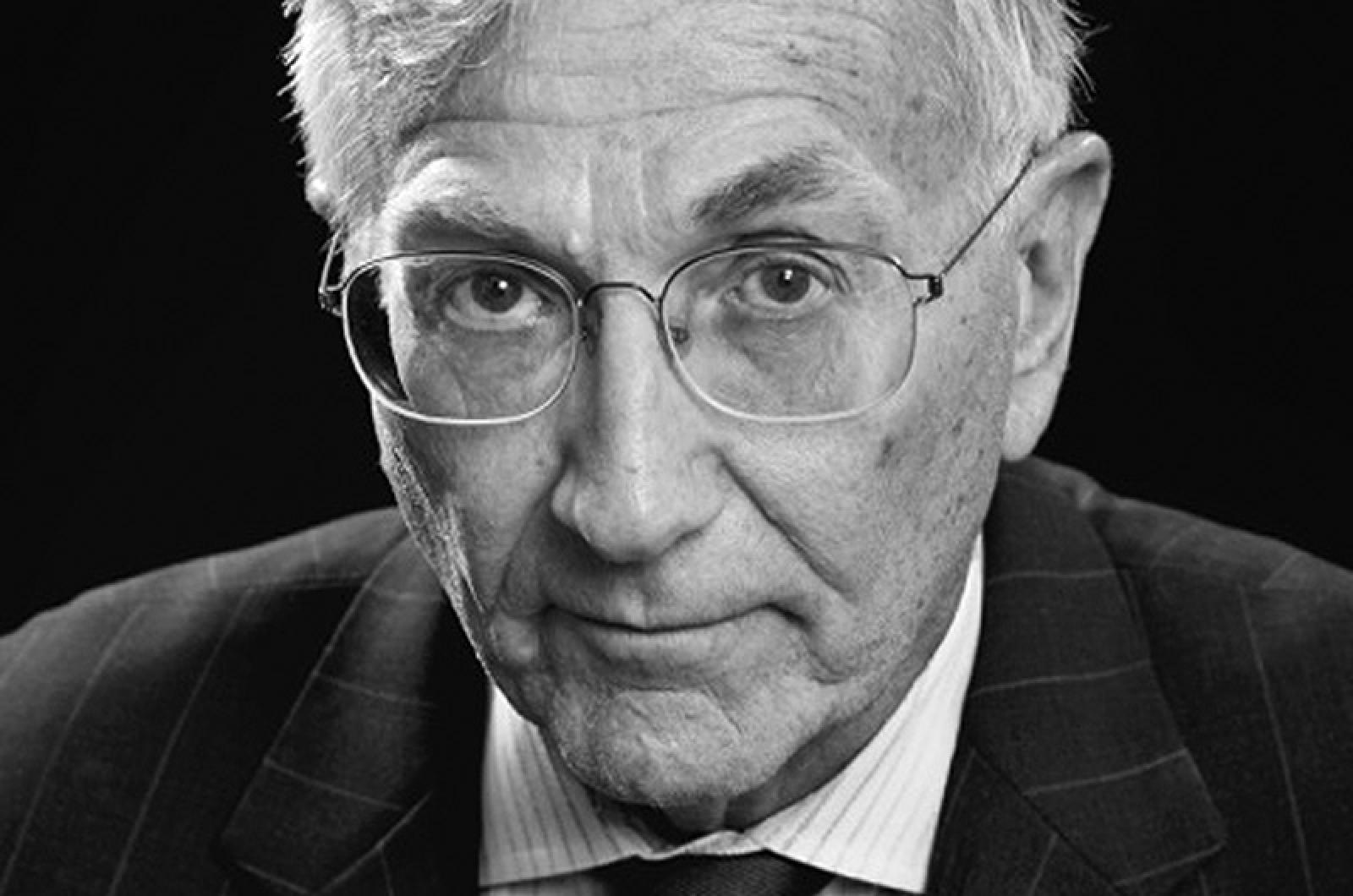

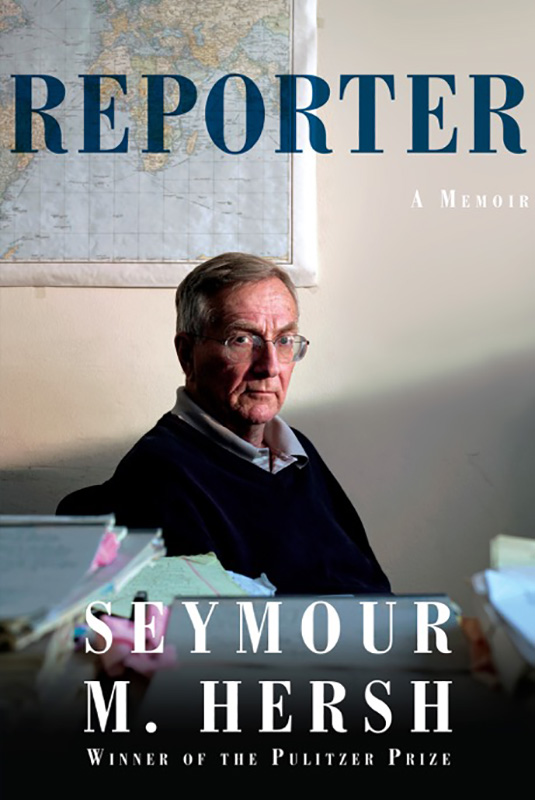

At some point, Seymour Hersh hijacked the conversation about his storied career in investigative reporting, and his new memoir Reporter, to tell a story about sailing.

The story had nothing to do with journalism, but it had everything to do with how Mr. Hersh parlayed a modest start covering crimes and fires on the streets of his native Chicago into a Pulitzer Prize winning career with the nation’s most prestigious news publications. The story was about how he once got into a sailboat race and convinced his sailing partner to adopt an unorthodox strategy.

“The only way to win, let’s just not do what everybody else does,” Mr. Hersh said, as he recounted the story in an interview with the Gazette this week. “At eight o’clock at night, we were rowing. We went the wrong way, we were gone, we were shot.”

Fortunately, Mr. Hersh did not choose a career in competitive sailing.

But by not doing what everybody else did, and by doing what most other people would not do, he turned his sometimes cantankerous zeal for questioning authority into one of the most successful careers in journalism.

Mr. Hersh will appear Sunday evening, July 22, as part of the Martha’s Vineyard Summer Author Series at the Chilmark Community Center, to talk about his career and his new memoir.

He is more than familiar with the Island, having spent parts of most summers on the Vineyard since honeymooning here with his new bride in 1964. Mr. Hersh said he and his family have rented a number of places up-Island for their summer vacations, including in earlier days several rather primitive accommodations near Tisbury Great Pond.

“We would rent places on a point that had no running water, but wow, you walk out and you’re 30 feet from the pond, and you could go out and collect mussels, cook them with some wine and a little pasta. Are you kidding, nothing better,” Mr. Hersh said.

He values most his up-Island isolation.

“We come now late summer,” he said. “It’s great. I tend to measure summers by how many times I have to go to Vineyard Haven. We don’t shop there, we shop up-Island, there’s all sorts of places to get veggies. You just go to Vineyard Haven to pick up people at the ferry. If I can go there once or twice a summer, I’m in heaven.”

Mr. Hersh’s memoir documents his childhood growing up in Chicago. His father died when he was a teenager, and he was charged with the task of running the family business, a cleaning store on the South Side.

After college, and a short and spectacularly unsuccessful attempt at law school, he got a job as a copy boy at the City News Bureau in Chicago. There he learned the basic nuts and bolts of journalism, under the thumb of relentless editors and more senior colleagues.

“The worst thing you could do at City News Bureau was screw up a story,” Mr. Hersh said. “Don’t make assumptions. Anytime you make an assumption the odds are you’re wrong.”

After a series of jobs at small newspapers and wire services he landed at the Associated Press, where he eventually got assigned to the Pentagon. There he soon ruffled feathers by walking out on a briefing which painted a rosy picture of progress in the Vietnam War, a picture he knew to be unjustified from his conversations with sources.

His Pentagon experience and his knowledge of military procedure proved invaluable a few years later, when he got a tip about atrocities being committed against civilians by U.S. troops in Vietnam. His research led to a series of reports on the massacre at My Lai. In his memoir, the account of tracking down Lieut. William Calley Jr., then finding a way to get his articles published reads like a mystery thriller, and demonstrated the tenets of hard work and persistence that marked Mr. Hersh’s career, which included long stints at the New York Times and New Yorker magazine.

Then working as a freelancer, his My Lai reports were eventually published by a tiny news bureau in Washington, D.C., but soon exploded on the front pages of every major newspaper around the world.

“I’d been a reporter for a decade by the fall of 1969 and somehow had figured out that the best way to tell a story, no matter how significant or complicated, was to get the hell out of the way and just tell it,” Mr. Hersh wrote in his memoir. “My first My Lai dispatch thus began, ‘Lt. William Calley, Jr., 26, is a mild-mannered boyish-looking Vietnam combat veteran with the nickname of Rusty. The Army says he deliberately murdered 109 Vietnam civilians during a search-and-destroy mission in March, 1968.’”

His work earned him a Pulitzer Prize.

His articles through the years reporting on chemical and biological weapons, the Watergate scandal, CIA operations in Chile, and mistreatment of Iraqi prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison brought him numerous other honors and awards.

“Journalism is a very much under appreciated art,” Mr. Hersh said. “Harder than people think. There’s a lot of easy ways to do it, but to make it work, it’s not that easy. It’s not fancy, it’s just the idea of finding some way into a story.”

Mr. Hersh’s work has its critics. In his book he describes his various battles with government officials and corporate interests on one side, and skeptical editors and lawyers on the other. He doesn’t spare himself in some of that criticism.

“I tell some bad stories about myself,” Mr. Hersh said. “Not everything was perfect. I got beat up a lot, and often with cause. That’s the way it goes.”

Working as he often does, well inside the unofficial channels of government, Mr. Hersh often relies on unnamed sources for his reports, a practice which often earns him criticism, especially from the people he is reporting about. But he counts unnamed sources as an integral part of investigative reporting, and says it is often the people with the higher sense of right and wrong who seek him out. He said his first loyalty, always, is protecting the source.

“You’re 22 years old, let’s say, in the military, and you’re bright,” Mr. Hersh said, providing an example of how he works. “You’ve got all this junk in your head, you’ve got all this stuff you can’t stand, and there’s a guy named Hersh who’s out there writing stuff that’s different than anybody else. I’m in the New Yorker, I’m making waves. So you find me.

“You meet in a working class bar somewhere and he tells you what’s going on. That’s how it works. It’s my job then to do something with what he tells me. If somebody’s troubled by that, that’s the only way you’re going to get the information. The critical thing is to have somebody inside who knows what’s going on.”

Mr. Hersh is troubled by the current state of his profession, especially outlets that present a news product designed to attract partisan readers and viewers.

“We’re a divided country, always, but the press is doing nothing but expanding the contrast,” Mr. Hersh said. “The divide is very extreme right now.”

While he decries the slashed budgets, reduced competition and diminished circulations of major American newspapers, he resists becoming cynical about the business.

“Now, there’s something called the Internet,” Mr. Hersh said. “It doesn’t matter where you write. You get something going and boom, it goes viral. I’ve had stories that had a million hits in 24 hours, break the computers in some places. It’s much more open, much more accessible.”

In the introduction to Reporter, Mr. Hersh calls himself a survivor of the golden age of journalism.

“It’s very painful to think I might not have accomplished what I did if I were at work in the chaotic and unstructured journalism world of today,” he writes in the book. “Of course, I’m still trying.”

Seymour Hersh will take part in the Martha’s Vineyard Author Series on Sunday, July 22 at 7:30 p.m. at the Chilmark Community Center.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »