The first time I fished for money I got burned so badly I never tried it again. My father had dropped me at Lobsterville Beach on an August evening back in 1979. All I had with me was a pole, two Rapala swimming plugs and a Hefty garbage bag. Hardly gear for a commercial-sized haul. But as the last bit of sun thinned out against Vineyard Sound there arose that quiet tingle that any fishing maniac recognizes as a harbinger of a good night to come. I could make out swirls and eddies near shore. I could hear the occasional slap of a tail on the water. And on my third cast the line drew tight with a pull I’d not felt before. Not a freight train opening run like a striper. Not a dogged zig-zagging like a bluefish. But something canny and unpredictable. Something that had to be played carefully lest the tender tissues in its mouth let go of the hook.

Soon the fish breached, all five pound’s worth, lilac and speckled up top with bright yellow fins on the ventral side. A weakfish. I’d never seen a fish so jewel-like and valuable-looking. Before the night would end I would fill my garbage bag with six of them.

“Holy crap,” my father said when he collected me from Lobsterville, “what the hell are you gonna do with all that?”

“I’m going to sell them,” I answered with bold assurance. “I’m going to sell them to Everett Poole.”

The next day I carried my Hefty into Poole’s fish market in Menemsha. Everett Poole, a character torn from the pages of Melville, slick with fish slime, took a puff from his trademark pipe and peeked into the bag.

“Nice haul, young fella,” he said, his wry eyes twinkling. “Going rate is 20 cent a pound. Take it or leave it.”

Everett knew my beautiful fish had only so much more time being beautiful. I turned beet red as he wrote out a sale ticket for five dollars and forty seven cents.

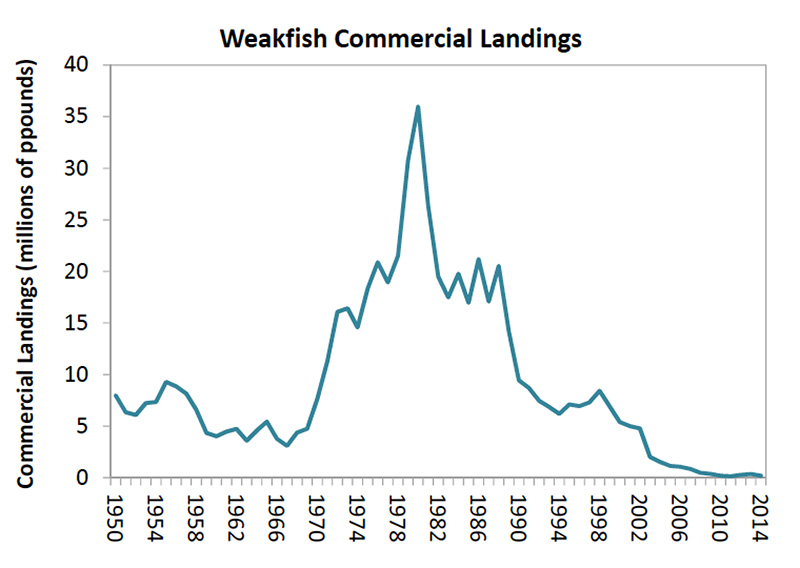

Today, nearly a half century later, the weakfish are gone. I’d venture even Everett Poole would pay a more handsome price were one to end up on his scales today. And at first glance it would seem that overfishing might be the culprit. A look at the National Marine Fisheries Service’s record of commercial landings shows an epic peak in that same year, 1979, when I sold all those beautiful fish for five bucks and change.

Mixed up in those commercial landings were large numbers of sport fishermen like me, slipping into backs of fish markets and selling off their excess catch to pay for gas.

Fishermen of course point to factors other than fishing when the conversation turns to collapse. While writing a Vineyard-based article for the Boston Globe in 2003, I interviewed Poole and reminded him of our 1970s weakfish transaction.

“Yep,” he said with a chuckle, “that sounds like me.”

But when I asked him where he thought all the weakfish had gone he told me he’d heard that large numbers of them had been spotted off the coast of Africa. Needless to say, our weakfish are not in Africa. We know from extensive population surveys that they spawn inshore in our bays and estuaries and migrate only as far as the American continental shelf off Cape Hatteras in wintertime.

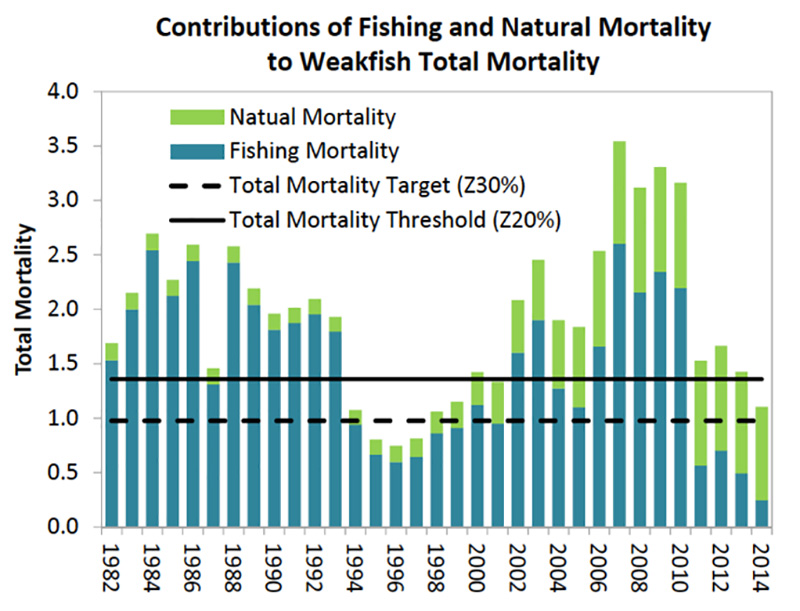

But where Poole and other fishermen are right is that something mysterious happens with weakfish apart from fishing. The rampant slaughter of the species has been markedly curtailed since my 1979 haul. Sport anglers can no longer sell them commercially and the daily creel limit is now down to a single fish in most states. Repeated commercial quota cuts have been instituted, each year more restrictive than the next. But unlike other fish like striped bass that we have managed back to viability weakfish just seem to keep spiraling down and down. Today weakfish death from “other causes” far exceeds the amount that die by fishing.

Is this non-fishing mortality ultimately our fault? With highly dynamic species it can be hard to tease a signal from the noise. As the noted author and conservation biologist John Waldman put it to me, “Weakfish have long had booms and busts at the northern end of their range. They explode in numbers when they have the right conditions, whatever they are. But they have short life spans and can fade quickly.”

The phenomenal fishing I experienced as a child casting off Lobsterville was just such a boom, and Waldman believes that another bonanza may lie in our future.

“The boom will come when for mysterious reasons,” Waldman wrote. “One year there will be a great match between larval weakies and plankton blooms that yields great recruitment. Then, deja vu all over again.”

But I wonder now during this extreme summer of ours whether non-fishing causes of mortality are being tweaked by humans in such a way that make déjà vu all over again ecologically impossible. Could it be that the continued removal of forage fish, like menhaden, from marine food webs is impeding the weakfish’s cyclical return? In spite of some recent cutbacks, menhaden remain the most caught fish in the continental United States with the overwhelming bulk of the catch happening in and around Chesapeake bay, one of the weakfish’s primary spawning grounds.

Could the ongoing surge in coastal development that continues to strip away salt marsh and sea grass, also prime weakfish habitat, be to blame? Or could it be the more vague fossil-fuel driven warming of the weakfish’s overwintering waters off North Carolina that is causing the problem? We don’t quite know. We just know that they aren’t here.

But in a way what’s more troubling than weakfish’s physical disappearance is that they are beginning to disappear from our memories. As I return to the Vineyard year after year and watch younger and younger fishermen cast from these shores, I realize that many of the newcomers don’t know this most gorgeous of marine animals. It is a classic example of what the marine ecologist Daniel Pauly called a “shifting baseline.” Each new human generation has a diminished sense of what is abundant and shifts its expectations accordingly. With weakfish, the expectation has shifted so markedly that today on Vineyard shores there is an expectation of none at all.

You cannot restore what you cannot remember. And so to all those fishermen casting swimming plugs into the setting sun at Lobsterville I offer up this memory. Once the evening sea swirled with the lilac backs of weakfish so plentiful that even a 10 year old could haul a half dozen to market.

Paul Greenberg is the author most recently of The Omega Principle: Seafood and the quest for a long life and a healthier planet. He will discuss his book Tuesday, August 21 at Maker’s Table, 110 Spring street, Vineyard Haven, beginning at 6 p.m.

Comments (11)

Comments

Comment policy »