Chappaquiddick Speaks by Bill Pinney, Stormy Weather Press, 2017, 398 pages, $19.95.

One of the lesser tolls of tragedy is the way it taints places. No one can look at the beautiful rolling fields of Gettysburg without mentally peopling them with the mangled corpses of men and horses. The prismatic loveliness of the Twin Towers when caught in the morning sunlight is now synonymous with fire and death.

Even Martha’s Vineyard has been touched by this: the scrappy, rustic peace of Chappaquiddick is colored permanently with a tragedy that’s now almost 50 years old.

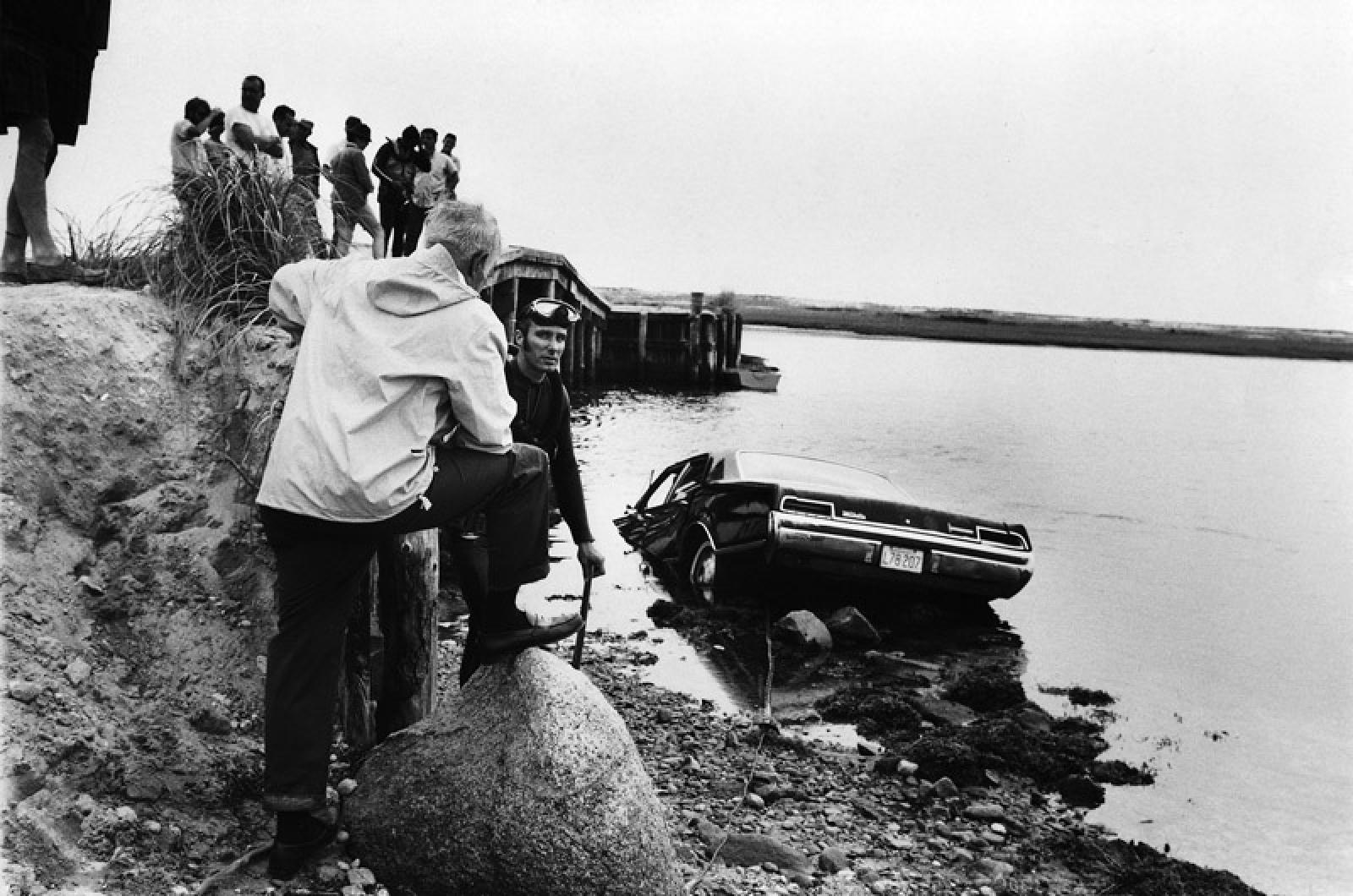

On July 18, 1969, young Massachusetts Sen. Edward Kennedy, after throwing a house party for the so-called Boiler Room Girls who had helped run his brother Robert’s presidential campaign, left the party at night and drove to the Dike Bridge with 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne. The car ended up in Poucha Pond with Kopechne trapped inside. SEnator Kennedy left the scene, and by the time he alerted authorities the next morning, Ms. Kopechne was dead. An inquest was held, and Mr. Kennedy was given a short and suspended sentence. He returned to the Senate, but the event would haunt his career for the rest of his life. Chappaquiddick is the main reason there was no President Edward Kennedy.

A steady parade of books on the incident followed (the most famous of which is probably Leo Damore’s 1988 Senatorial Privilege), and one of the latest is Bill Pinney’s searchingly and ferociously detailed new book Chappaquiddick Speaks, in which the author interviews a new witness and puts forward an explosive alternate theory of the case. Regardless of what his readers end up making of his claims, no one interested in the Chappaquiddick tragedy can afford to miss this book.

Ted Kennedy’s version of what happened describes a tragic accident. He claimed that he and Ms. Kopechne had no illicit intentions when they left the party, that he’d had nothing to drink and definitely wasn’t drunk, that he wasn’t driving particularly fast, that he was able to escape the semi-submerged car and tried unsuccessfully several times to free Ms. Kopechne, that he then hurried back to the cottage where the party was winding down, gathered a couple of friends, and returned to the sunken car, where they tried again to rescue Ms. Kopechne, again without success. He returned to his hotel room in Edgartown and around 10 the following morning contacted the police to tell them what had happened. By then of course it was too late to save the young woman trapped in the car. Senator Kennedy admitted to panic, confusion and poor judgment, and that was the end of the matter.

Just as with the assassinations of the Kennedy brothers years before, this official version of events immediately struck many people as enormously unlikely — in this case, mainly born of the fact that Senator Kennedy’s behavior that night on Chappaquiddick very much seemed like the actions of a guilty man. If he knew Mary Jo Kopechne was trapped in a submerged car, why did he not raise a general alarm, pounding on doors at any of the darkened cottages in the immediate vicinity of the accident? Why did he wait until morning to report the catastrophe to the police? Seen from the vantage point of an outsider, it very much looked like a drunken junior senator panicked at the thought of what Dike Bridge could do to his political career.

That would be reprehensible enough, but from the start there have been people who believed far worse. Bill Pinney is one of those people, and after carefully re-examining the area, the surviving physical evidence, and the records (including phone logs), he has reconstructed a version of the Chappaquiddick incident that isn’t so much a callous crime of panic and negligence as it is a conscious scheme of murder and concealment.

Pinney touts the new witness he has brought forward for this book, Carol Jones, who was 17 in 1969 and driving on the Chappaquiddick Road when she says a car passed her at high speed on the deserted road, lodging in her memory because of how unusual and dangerous it was for anybody to drive in such a way on the island’s dark lanes. A new witness is a good hook for a new book, but of course this testimony is worthless; Jones didn’t know what time it was, her memory could easily have been contoured by the tragedy’s ubiquitous infamy, and in any case she couldn’t have identified the other driver or passengers.

It’s the author’s main theory that’s the meat of the matter. He asserts that Mr. Kennedy was drunk at the wheel and side-swiped some parked heavy construction equipment in the dark, denting the passenger-side door, shattering the window, and knocking Kopechne unconscious. Mr. Kennedy feared she was dead. He left her in the car, jogged back to the cottage, enlisted helpers, and returned to the car, where everybody likewise assumed Ms. Kopechne was dead. According to Bill Pinney, this group rigged Kennedy’s car to drive off Dike Bridge, with ropes securing the steering wheel and a weight to hold down the accelerator. They slipped Ms. Kopechne’s body into the half-submerged car, unknowingly drowning her. The author believes that Senator Kennedy, desperate to avoid what he thought would be a charge of vehicular homicide, staged the accident at Chappaquiddick in order to make it look as though Ms. Kopechne had driven the car off the bridge alone.

It’s intentionally provocative stuff, written with an unapologetic directness. Mr. Pinney has raked over every tiny scrap of evidence and testimony, and quite apart from anything else, his book represents the most exhaustive forensic reconstruction of the incident that’s ever been made. Everything is here: timelines, photos, diagrams, charts, all of it laid out with a clarity and urgency that will keep readers absorbed despite the fact that half a century has passed and all the principal actors in the story are long since dead, and despite how incredibly unlikely it is that a group of midnight partygoers would concoct a Hitchcockian scheme with ropes and counterweights on the spur of the moment with their minds running in a hundred different directions.

There is no shifting the stain from the name of Chappaquiddick. Nothing that Bill Pinney or anybody else can write will stop people from associating a pretty little island with a poignant tragedy. But at its heart, Chappaquiddick Speaks succeeds in raising questions about that tragedy, some of which can’t be easily answered.

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »