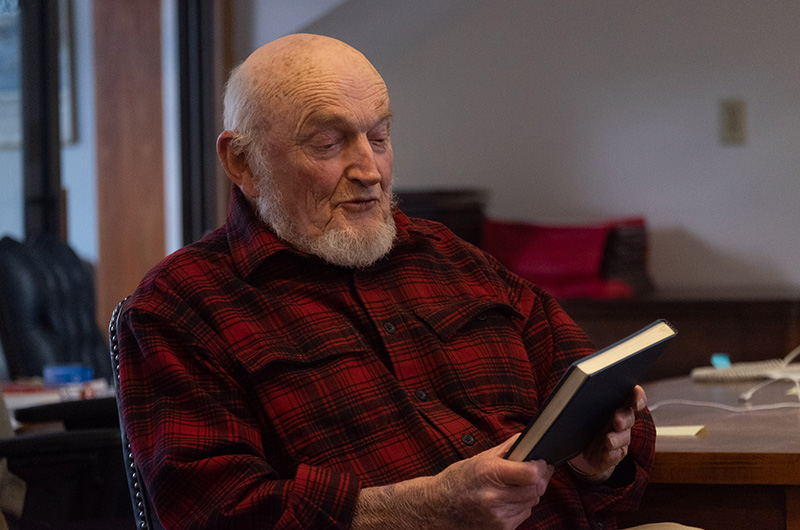

Everett Poole, the 88-year-old straight-talking Chilmark moderator who’s nearly as storied as the institution of the New England town meeting itself, visited the Gazette last week to tell tales from his 40-plus years behind the podium.

The discussion was part of the Gazette’s monthly off-season speaker series, Tuesdays in the Newsroom. But according to Mr. Poole, the Gazette had it all wrong in asking a moderator to speak.

“The moderator is not supposed to talk,” he corrected with a smile. “All he has to do is keep people on the subject, which is not easy sometimes.”

With about twice as many people in attendance as the requisite 25-head Chilmark quorum, Mr. Poole did a fine job of both tasks, leading a humorous and informative discussion about the moderator’s role in the three-centuries-old New England practice that many consider one of the world’s purest forms of democracy.

Mr. Poole was elected Chilmark moderator from the floor during a scrappy 1976 town meeting. He’s been re-elected every year since. What’s his secret?

“No one else wants the job,” he said, holding up his town meeting handbook. “For $27 — it used to be $20 — you can buy this book from the state. And if you read that, anybody can be a moderator.”

Despite his humility, Mr. Poole admitted that certain traits and practices make the job go more smoothly. In his more than 40 years on the job, he’s learned how to handle the rabble rousers, who he says appear at every town meeting, regardless of the issues.

“I let them talk, but I don’t let them get off subject,” Mr. Poole said. “You have got to let them have their say. You have got to let them get it out. And you have to let someone else prove them wrong.”

If someone goes on too long, Mr. Poole said he might simply interrupt and ask if the person has anything new to add. For voters who don’t abide by that dictum, Mr. Poole takes a different approach.

“I ignore them,” he said.

He grew up in Chilmark and said quite a bit has changed about the age-old institution of town meeting since his early years.

“Years ago when I was a child, and that’s a long while ago, town meeting started in the daytime,” he recalled. “Ladies from the church served lunch and it was a big deal, and children from the school were marched over and sat in the front row. By the time we were old enough to know how to vote, we really knew how town meetings ran.”

Commenting in part on the changing demographics in town, he said most voters today “come from away” and need instruction in the intricacies of town meeting etiquette.

“When I first started, I could call everybody by name,” Mr. Poole said. “Now I may recognize 30 per cent, and maybe only know 20 per cent by name.”

Regardless, he said town meeting remains one of the most important days of the year — and one of the only times when he will be seen wearing a necktie.

Turning serious, he said it is vitally important that young people attend the meetings.

“What we do today is going to affect them 20 years from now,” Mr. Poole said. “It’s important . . . we get mostly retired people who don’t know what it’s like to earn a living on Martha’s Vineyard. They want a big police, fire, and ambulance department, but they don’t know what it takes to provide that.”

He said the hardest task for a moderator is choosing special committees — something he last had to do with the Squibnocket Beach issue. He also recounted the time he was threatened with his own gavel by an angry voter.

On three occasions over the years, he decided to hand the gavel to the town clerk and step down from the podium to speak about an issue on the town meeting floor.

“I’ve done it, but I don’t recommend it,” Mr. Poole said. “Most town meetings in Chilmark, if you came up to the podium after the meeting, you’d find it was all red because that’s where I was biting my lip.”

Although he wasn’t there to tell fishing tales, he compared a moderator with the captain of a whaleship.

“It’s pretty simple,” Mr. Poole said. “When whaleships left the country, when they got outside the three-mile limit, the skipper would call everybody aft, and he would instruct the mates on their duty. And he would tell the crew, there’s one more thing to remember boys: when you see me in town, I’m Mr. So-and-So. But when we’re on this ship and out here beyond this three-mile limit, I’m God almighty.”

Comments

Comment policy »