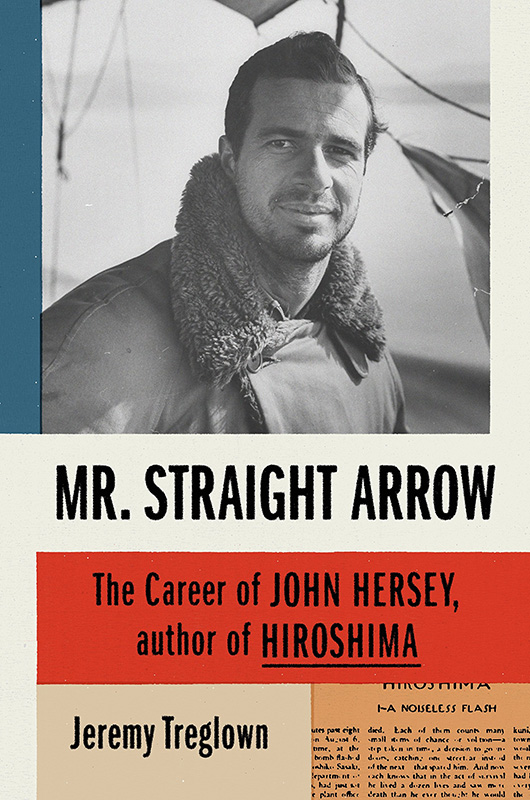

Mr. Straight Arrow: The Career of John Hersey, author of Hiroshima by Jeremy Treglown, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019, 384 pgs., $28.

Biographer, critic, and former TLS editor Jeremy Treglown’s terrific new book Mr. Straight Arrow is a biography of author John Hersey and a gripping account of his working life. Despite its length and variety, despite its honors and intricacies, that career can be summed up in the minds of most writers in one single book: Hiroshima.

Hiroshima first appeared in 1946 as an entire issue of The New Yorker (the only time the magazine had ever conferred such a distinction), caught the imagination and tortured the conscience of a vast swath of the reading public (New Yorker editor Katharine White wrote him a note saying the book made her “sleepless but thankful”), and inadvertently put such a deep stamp on Mr. Hersey’s career that for most people that career consists of one slim book. The subtitle of Mr. Treglown’s book is “The career of John Hersey, author of Hiroshima.”

He wasn’t only the author of Hiroshima, of course. In fact he was a well-known author before that book ever appeared. His debut, Men on Bataan, appeared in 1942, was the first book to give American readers a journalistic look at the war in the Pacific, and his follow-up, Into the Valley, “made his name as a war writer,” according to Mr. Treglown. And there were many books to follow, including The Wall, A Bell for Adano (for which he won the Pulitzer Prize), The War Lover and The Child Buyer.

But he’s remembered for that one brilliant, stark, horrifying book. Hiroshima was widely read, has been perpetually in print, is a staple of school curricula, and is very likely immortal. Even after more than 70 years, Hiroshima still halts and harrows the reader.

Mr. Treglown traces Mr. Hersey’s whole life, from his time doing writerly secretarial and general gopher work for bestselling author Sinclair Lewis in Stockbridge in the 1930s, through his years as a journalist, to his career as an author and public intellectual. Mr. Hersey also kept up an extensive correspondence, including with close friends like Lillian Hellman.

The Hersey papers (as yet not fully catalogued) take up a series of boxes at Yale’s Berneicke Library. The John Hersey who emerges from these pages is a thoroughly adult and curiously engaging figure, a quiet professional who might otherwise get lost in the roster of larger-than-life literary figures who were his friends, colleagues and enemies. Mr. Treglown is unfailingly insightful about such contrasts.

“Many people in Hersey’s wider circle were alcoholics, at least by today’s standards, and his moderation as well as his seriousness about life and everyday decisions increasingly separated him from some of them,” he writes. “Some [of those friends, like fellow Vineyarders Lillian Hellman and William Styron] described his calm as almost Confucian. His life had friendships, variety, prosperity, and — what for a while seemed to distinguish him from so many others — stability. The house was built, trees were cleared, and the garden was coming along.”

In an approach Mr. Hersey would have appreciated, very little in the book is allowed to disturb this tranquil surface. Mr. Treglown catches Mr. Hersey’s understated humor wonderfully and he tends to downplay the rare controversy that touched on his hero’s life. Annalee Jacoby, for instance, the widow of Mel Jacoby on whose Bataan articles Mr. Hersey had heavily relied for Men on Bataan, spent years making credible accusations of plagiarism against him. Mr. Treglown notes those accusations (just as he had earlier noted the many strong similarities between Mr. Hersey’s novels and Mr. Lewis’s books) but puts up a wan defense, making reference to Mr. Hersey being “accustomed to the pooling of information in a newspaper office and to the authorial anonymity of old-style journalism,” as if journalists somehow don’t know they’re plagiarizing when they’re doing it.

Mr. Hersey’s love of his longtime home on Martha’s Vineyard, so beautifully reflected in his 1987 book Blues, is likewise a thread running through the book’s second half. He was drawn to the place for many obvious reasons and one perhaps less so: his friendship with Ms. Hellman.

“Since their Moscow days the stormy, hilarious, self-dramatizingly radical, hard-living Hellman had always been Hersey’s doppelganger,” Mr. Treglown writes, “challenging his opposite personality while extravagantly voicing many of his sociopolitical beliefs.”

John Hersey died in 1993 at the age of 78, and his ashes are buried in the West Chop Cemetery. Readers coming to Mr. Straight Arrow knowing only Hiroshima will find an entire world they never expected and will very much want to explore.

Comments

Comment policy »