In the late summer of 1953, the artists Thomas Hart Benton and Denys Wortman sat for each other in Benton’s Chilmark studio for what became a dual portrait session, dubbed “the Battle of Beetlebung Corners” (sic) by Collier’s magazine that October.

“They are great friends. But beetle-browed Tom Benton is a spirited soul who likes nothing better than a fight,” the article read. “Last month he challenged the placid Mr. Wortman to the most sophisticated duel since medieval poets flung verses at one another: He suggested that they oppose artistic talents in a match to see which of them could produce the better portrait of the other.”

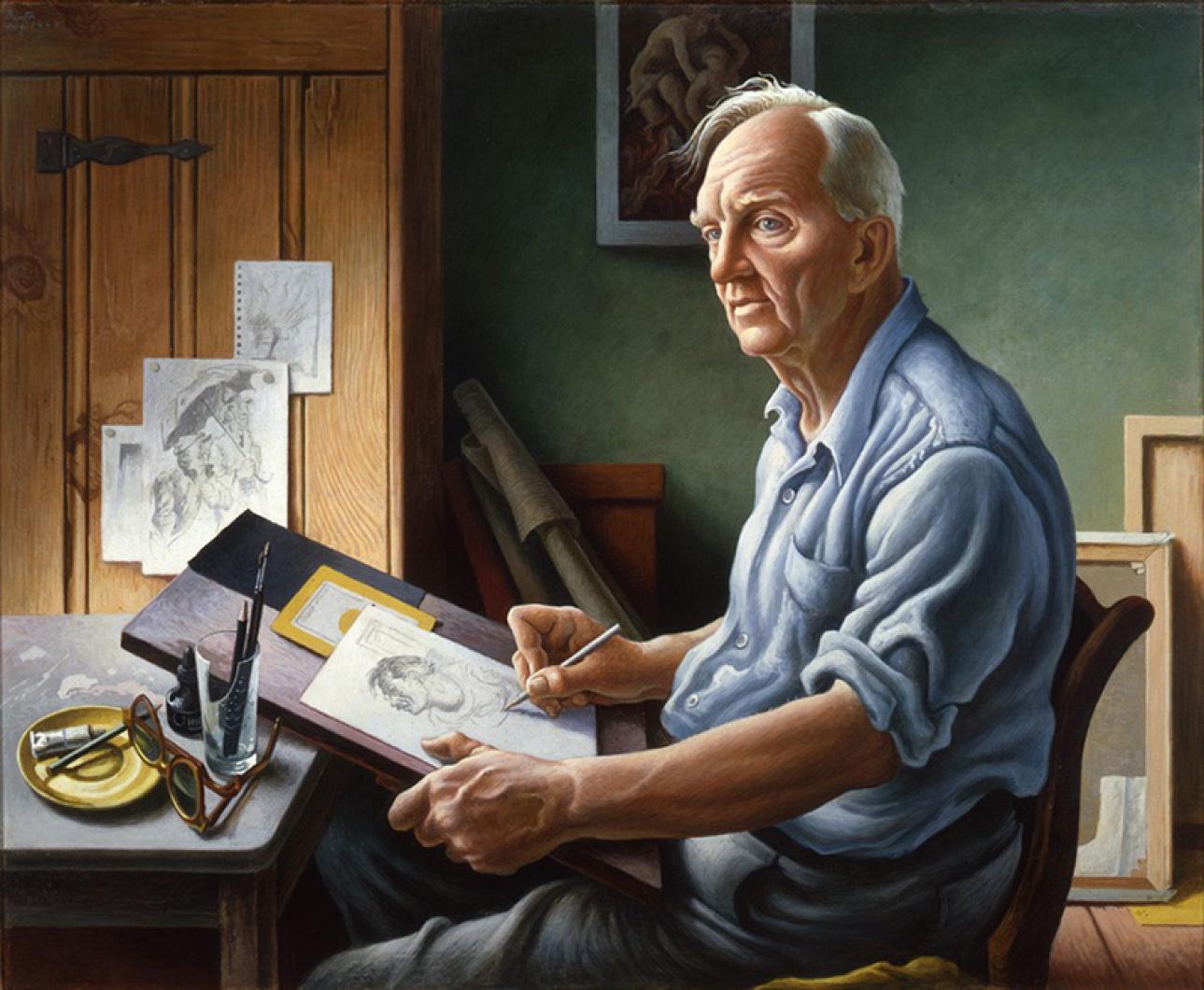

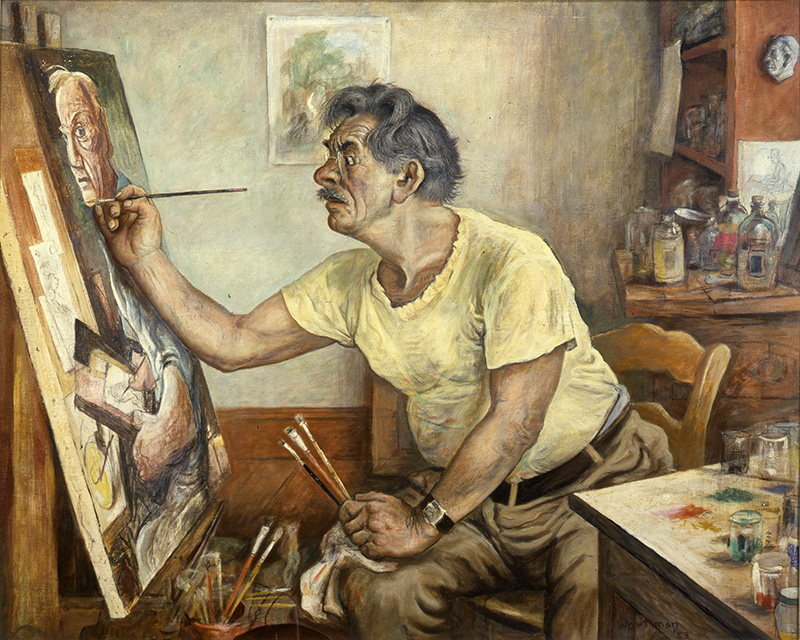

The resulting two 40” x 30” oils on board, Wortman’s Thomas Hart Benton Paints Denys Wortman and Benton’s Denys Wortman Paints Thomas Hart Benton, soon left the Island. Sandy Low, a Vineyard summer resident and founding director of the New Britain Museum of American Art, purchased them both in 1954 for the Connecticut museum where they have resided as neighbors ever since.

This weekend, the portraits are returning to the Vineyard for the first time since they were new, loaned by New Britain for the Martha’s Vineyard Museum’s new Benton exhibition titled Benton’s Martha’s Vineyard. The show, which opens Saturday and runs through August 11, is the first major Benton exhibition on the Island where he painted and relaxed for more than 50 summers. The opening of the exhibit coincides with the museum’s Evening of Discovery grand opening gala on Saturday night.

With paintings on loan from private collections as well as New Britain and other institutions joining the museum’s Benton works, the exhibition traces the influence of Martha’s Vineyard on the painter’s art after he arrived here in 1920. The surging waves and dramatic cliffs of up-Island fired Benton’s imagination, and he found inspiration in the Islanders who made their living by land and sea.

"To me, the most important element is that he quite dramatically turned his back on abstract modern art,” Vineyard author and Benton biographer Polly Burroughs told the New York Times in 1981, more than six years after the painter died at 86.

“Nature got to him on the secluded Massachusetts island. He told me, ‘It was in Martha’s Vineyard that I first really began an intimate study of the American environment and its people,’” Ms. Burroughs told Times reporter Herbert Mitgang. “Most people thought he was strictly from Missouri in his outlook.”

The dueling Benton-Wortman portraits also fit into the artist’s Vineyard story: both men had been Island summer friends for some 30 years, though their artistic careers off-Island took different paths.

Benton remains famous for his murals and paintings celebrating American life, from placid rural farmers to dynamic railroad trains. Less well known today, Wortman was a long-running syndicated cartoonist known for Mopey Dick and the Duke, a pair of down-on-their-luck Everyman types whose single-panel appearances always came with a caption wryly commenting on current events and popular culture. For example, a panel from April 1939 read: “Do you remember, Mopey, when you could read a newspaper just to forget your troubles?” Another from December 1952: “Just for the fun of it, let’s turn the television off for a little while and see if we could entertain ourselves.”

Before his cartooning career, Wortman was a painter, originally influenced by Impressionism. In 1913, he took part in the controversial New York Armory art show that introduced Cubism, abstract art and other French innovations to the United States.

When it came to painting his friend Benton, Wortman applied both his sardonic wit and his considerable studio talents to capture the glaring, disheveled artist at the easel in the act of painting his friend Wortman. The cords on Benton’s neck stand out as he clutches three paintbrushes in his left hand, a fourth in his right touching up Wortman’s chin, above which the cartoonist’s left eye stares out Cubist-style from the painting-within-a-painting.

In Benton’s actual portrait of Wortman, both eyes look mild and searching. The cartoonist’s board is balanced on his lap as he sketches his friend at work. Where Benton’s easel is surrounded by jars and colorful blots of pigment, Wortman’s borrowed tools are few: a bottle of India ink, a saucer, some pens in a glass with a large chip missing.

Does the broken vessel suggest a whiff of disdain by the established painter for his friend, who squandered his early gifts on mass-market cartooning? Certainly, Benton wasn’t pleased to hear that the New Britain Museum of American Art had plans to put Wortman’s portrait of him on the cover of the catalog for a mid-1950s retrospective of Benton works. He felt that a “caricature portrait” would undermine the serious nature of his own painting.

“(A) wild-eyed, crazy son of a bitch, it does make me,” Benton complained, in a letter to Sandy Low. “You might just as well use Toulouse-Lautrec’s picture of the absinthe drinker.”

Benton’s Martha’s Vineyard makes its debut at Saturday night’s museum gala and will be open to the public at no charge as part of the opening day festival Sunday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.

Regular museum hours are Tuesday from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. and Wednesday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. The café closes at 3 p.m. For more information, visit mvmuseum.org.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »