At 4:30 a.m. Menemsha Harbor is glassy and the only sounds are the hum of Menemsha Fish House’s vibrating refrigerators and the early-morning summer bird opera. The Little Lady slices through the flat water, heading out for a morning of dragging.

Stanley Larsen in his boat Four Kids is not far behind. He just has to sort out a few things with the engine first.

A quart of sweating lemon-lime Gatorade and a giant spool of mint-colored line wrapped in plastic stand out in their newness on the deck of Four Kids, which is littered with hundreds of feet of old green line, plastic baskets holding trash he’s collected from the ocean, big black totes for fish, faded orange and yellow buoys, banged up coolers and treadless tires that serve as bumpers.

Stanley’s assistant, Eric DeWitt, deftly navigates the mess and sorts the black totes. Eric is in his early 60s and this is his second summer working with Stanley. A former vet tech and manager of Island Alpaca, Eric is soft-spoken, focused on getting the boat ready to drag for fluke.

Meanwhile, Stanley, who has been tweaking the boat’s engine down below, emerges and casually casts off. The boat drifts away from the Richard & Arnold, his other craft he co-owns with Eric, and the dock. Stanley takes the helm and shifts into a forward gear.

It’s a late start. Stanley usually likes to get going at around 3:30 a.m.

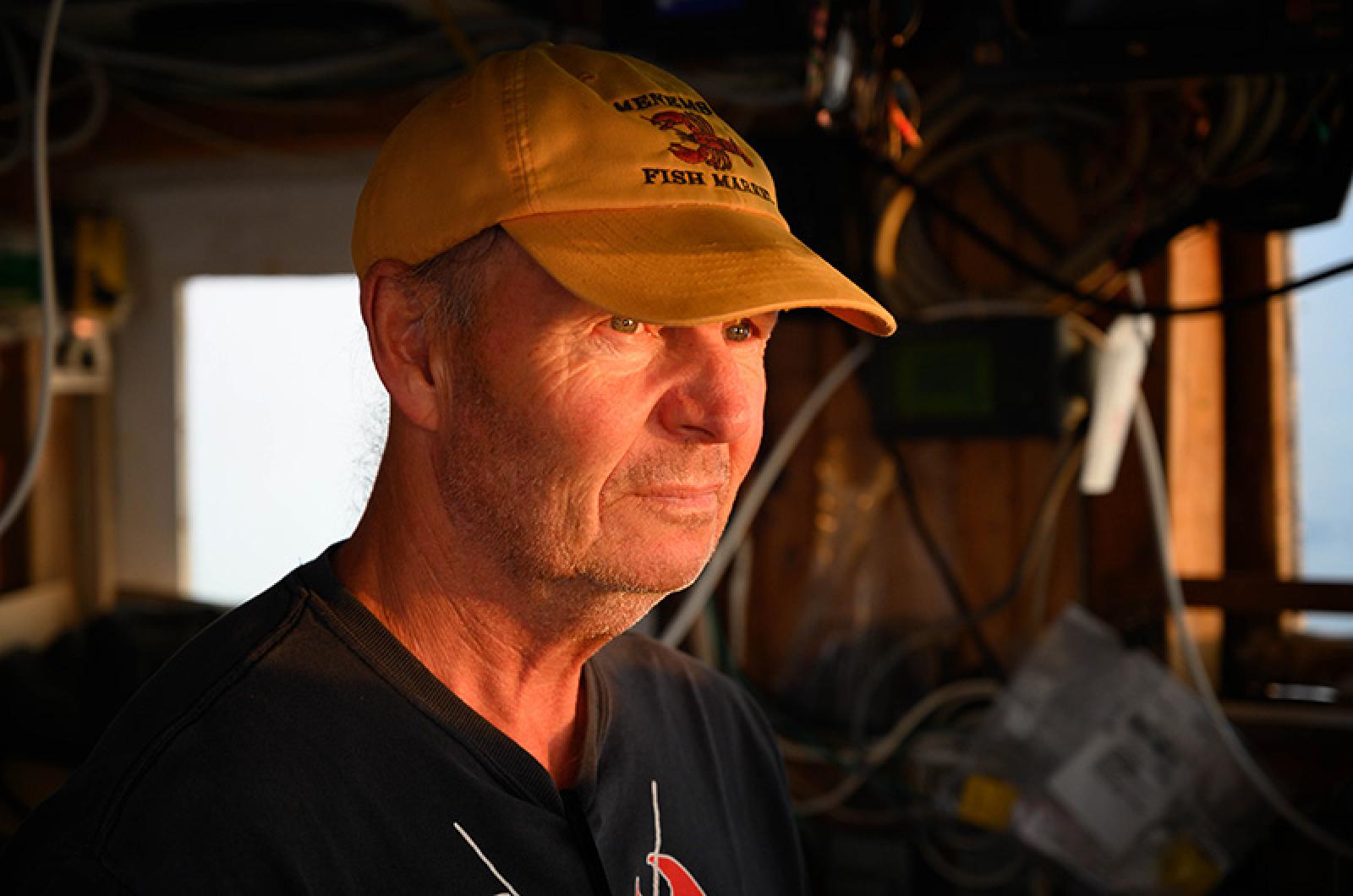

“Then I can go further offshore and do longer drags,” he explains adjusting his baseball cap. “I like a two-hour drag. Closer, I can only do 20 or 30 minutes and then I’m in the mud.”

As most know, Stanley is a member of the Island’s legendary Larsen fishing family. The firstborn son of commercial fisherman Dagmar and Carol Smith Larsen, he grew up in the “first house on Flanders Lane.” His sister Deborah now lives on the Cape and his sister Lisa lives in Vineyard Haven. He and his brother Karsten still live in Chilmark. While his father lobstered, his mother Carol was the town custodian and raised four children.

“I used to love going to work with her and helping her,” he recalls. Carol would occasionally help with scalloping in the winter. “She was a Smith. Same family as Bill Smith. She was a great, great mom to us. We put her through a lot. That’s for sure.”

When Stanley was a boy his father would regularly wake him up in the middle of the night to go fishing.

“It would be because the crew didn’t show up or they did and they were drunk,” he says. “My dad couldn’t go out alone, so he would drag me out of bed to help. My mother would cry every time we left. We’d go way out to the Canyons, 80 to 100 miles off shore. We’d be gone for three or four days. In the winter, I’d miss school and it would be freezing. Fifteen to twenty-foot seas, straight up and down. We’d have to tie everything down. I would be sick the entire time. Couldn’t eat. Dry heaves. The boat would thrash and shudder. It could get scary. Our lobster lines were sometimes up to 2,000 feet long. We’d pull them up and they’d be chock-a-block full of lobsters. We’d pack the lobsters on ice on their backs in galvanized trash cans with holes in the bottom so they wouldn’t drown in the melting ice. The biggest lobster I’ve ever gotten was 40 pounds.”

On this day, as the Four Kids slides out of the harbor, Stanley does not feel optimistic.

“I don’t have high hopes for a lot of fish this morning. In the seventies it was great. There used to be 40 to 50 boats. We’d get as much as 15,000 pounds of fish a day. Nowadays if you get 200 pounds you’re doing really good. We didn’t think it was ever going to end. But now the balance is completely gone. We’ve over fished and polluted the ocean.”

He limps to the back of the boat and asks Eric to help set the net out. He winces as he moves a line.

“I have an MRI this afternoon,” he says. “I think I tore my right rotator cuff. It hurts even when I sleep. I was trying to force something and I shouldn’t have. I should know better. What a beautiful sunrise.”

He turns his attention back to the net. “See how nice and clean that is? You won’t even be able to tell it is a net after the first drag because there will be so much seaweed in it. That’s why you’ll see so many guys back on the dock, picking their nets.”

He spies a hole and grabs a small piece of cord, and he and Eric get to work mending it. “We use mostly half hitches.”

He moves his shoulder the wrong way and flinches again. “Over the years, there have been so many close calls. One bad move and that could be it.”

Twenty years ago he nearly lost his right foot.

“I was down in the fish hole when my pants got caught in the coupling of the propeller shaft and pulled my foot in. I was alone, three or four miles off the south side of the Island. I thought I was going to have to cut my foot off. I called the secretary at town hall on the radio and she called my brother Karsten who called the Coast Guard and they came and picked me up. Then I had several surgeries to fix my foot. Now it is just arthritic. I still can’t believe my foot didn’t even stall the engine.”

He chuckles and moves back to fishing and talking about the philosophy and net setup for dragging.

“The chain tickles the fish. Fluke like to sit in the muck. We’ll use these metal doors that weigh 400 to 500 pounds as ballast to keep the net open and the nets from getting too caught up on the bottom. The more even everything is, the better the net fishes. Sea bass just opened yesterday. I don’t have any lobster pots. My father cured me of that.”

Eric and Stanley let the lines out. The net is about 125 feet long and 80 feet wide. Stanley bought the Four Kids from Timothy Broderick. Its original owner was “Bobby somebody.” The boat was built in 1976, and from the looks of it still has the original teal and white gingham curtains. From a few flecks of blue paint, it looks like the floor color once matched the curtains. As with the deck, the boat’s cabin is filled with detritus. Even though the craft is old, the engine is in excellent shape.

“Timothy did a lot of work on it. It’s a 330-horse Detroit diesel. He’s one of those guys who can fix anything.”

At around 6:30 a.m., as the sun comes up over Menemsha Hills, they pull up their first drag. They catch a bunch of fluke, along with a mess of crabs, one cod, some sea robins, skate, conch, scup and a few squid. They dump the fish, sort it, and reset the net. Stanley and Eric say maybe three words to each other throughout the process.

Stanley throws a piece of plastic that was caught in a net into one of the plastic baskets. “There’s a lot of plastic these days. Other than plastic, I’ve caught a few odd things: a motorcycle seat, a big piece of metal that might have been part of an ordnance and a bale of pot.”

He sits back down in his captain’s chair for the next drag.

“I’ll probably sell the fluke to Betsy [Larsen]. I sell a lot of lobsters. I’m the only one in Menemsha who keeps their market open year-round. They are all a lot smarter than I am. I keep doing all of this to keep my licenses up. To keep my endorsements.”

As he talks, he points to a pile of papers that he has to submit and his logbook that he keeps to track where he fishes, what he catches, how much he catches and how much fuel he uses. He can catch up to 300 pounds of fluke and sea bass, but he doubts he’ll even have to consider the limits today.

“The bluefish haven’t even shown up this year. Very few striped bass keepers. When I was a kid, we would walk down Menemsha beach and catch one after another.”

He points down the Sound. “I have a mussel farm down there, about three miles east. It’s about a half mile long rope. I have to sink the line deeper in the summer for boat traffic. In the winter I can bring it up to about 15 feet. I have to check it biweekly. I have about a thousand pounds of mussels now. I keep trying things. Oyster farms are lucrative, but so much work. I admire the young guys who are taking that on. The last few years Whole Foods has cornered the market on Canadian-harpooned swordfish. There haven’t been many this year. I’ve only heard of one so far.”

Fishing was inevitable for Stanley. As he tells it, nothing else occurred to him. He graduated from high school three months early and followed his father to fish in Panama City, Fla. His father bought a swordfishing boat and after four or five months, they brought it back up to the Island. Stanley was about to buy his own a shrimp boat rigged for harpooning when his father was diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Stanley took over his dad’s boat, the Carol L., and began swordfish harpooning and dragging Georges Bank. He was also the shellfish constable. When he was in his early 20s, he married Cheryl Kuttner and they had three children. His daughter Tanya now works at Howe’s House. Son Erik works on tug boats and barges in Boston. Son Nathan works for Vineyard Gardens as a foreman.

He doesn’t talk much about early fatherhood, which he describes as a “blur,” but he does talk about a significant change of heart.

“I’d be doing these long drags, three to four hours, and needed something to read. I found my dad’s Gideon’s Bible on board the boat. I read it cover to cover. And I had questions. I went to talk to the priest at the Menemsha church. He said he could answer them. We made an appointment. But then when I went to see him to talk to him, he never showed. At the same time, I had a guy on my boat who was Jehovah’s Witness. I never had thought much about it, but I began to talk to him. I got curious and sought them out. It just made sense to me. There are no divisions. No race. No color. No hierarchy. I still have my dad’s bible at the fish market.”

He met his current wife Lanette through their ministry 28 years ago. They have a daughter Janelle who helps out with the fish market, which they bought from Donald Poole in 2004. “Lanette is the one who came up with the slogan: The whole fish and nothing but the fish.”

Stanley and Eric pull in the net for a third time. More fluke, more crabs, more sea robins, a codfish, numerous horseshoe crabs and a few large quahogs. It’s 8:30 a.m. and they have about 60 pounds of fish. Stanley decides to call it a day on the water. The market opens at 11 a.m. and he has paperwork to do.

“When it is not life threatening, fishing can be pretty boring,” he says on the way back in. “On long drags you read, work on gear and try to sort through the mess. Then you pull the fish in and make a mess. Then you clean up the mess and start up all over again.”

Comments (11)

Comments

Comment policy »