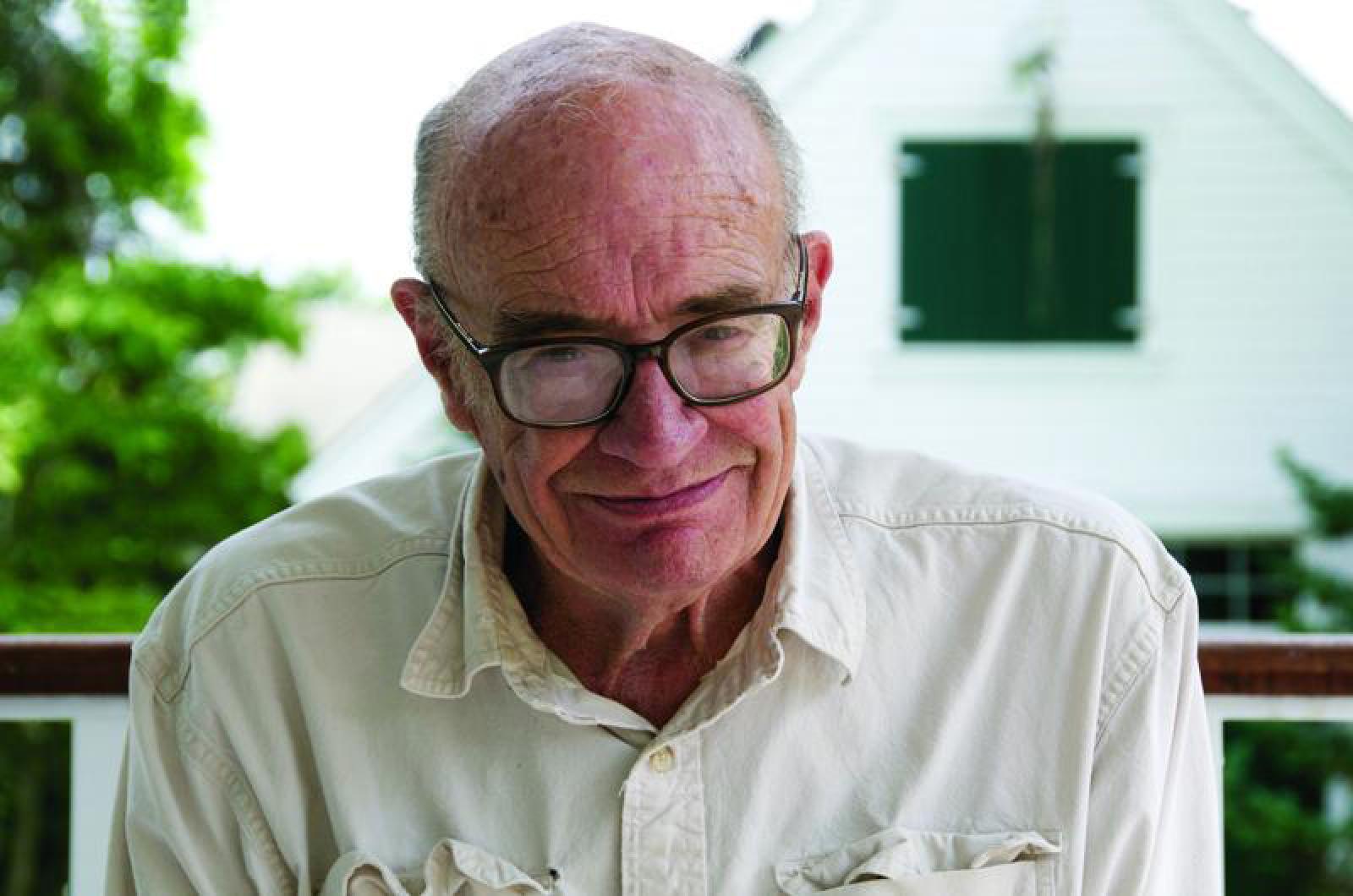

Ward Just, the son and grandson of newspapermen who went on to help define a new era of journalism as a war correspondent in Vietnam and later became a critically acclaimed novelist, died on Dec. 19 after a struggle with Lewy body dementia. He was 84 years old.

A seasonal resident of the Vineyard since 1979 and a full time resident since 1992, Mr. Just was known around the Island and worldwide for his kind manner, wit and legendary work ethic.

“He wrote all day, every day,” said his wife, Sarah Catchpole. “He started after breakfast at 9 a.m., took a break for lunch of a bologna sandwich and glass of milk, then wrote again until 6 p.m. The routine was steel, iron clad. You could interrupt him, but it wasn’t a pleasant experience.”

The result of this effort was 19 celebrated novels — Echo House was nominated for a National Book Award and An Unfinished Season was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. He was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2013.

Ward Just was born in 1935 in Waukegan, Ill. His grandfather, Frank H. Just, was the editor and publisher of the Waukegan News-Sun, where Ward got his start in journalism, becoming a cub reporter at age 17, working for his father, F. Ward Just.

Mr. Just would eventually leave his hometown to work as a reporter for Newsweek and The Washington Post, covering the seminal political events of the 1960s and 70s. While working for Ben Bradlee, the famed editor of the Washington Post, Mr. Just covered the Vietnam War, embedding himself with the troops, and with a handful of other young journalists including David Halberstam, Seymour Hersh, Stanley Karnow and Michael Herr, helped usher journalism into a new age, one that told the full, uncensored story of what war was really like.

While on assignment he was injured in the battle of Dak To, a village about 15 miles from the Cambodian border. In an interview for the Martha’s Vineyard Magazine, he described the experience this way: “The idea was to try and find where the enemy was. And so we just kept going along these paths. Plainly the enemy had been there but we didn’t know where the hell they were. And I never quite understood, once we found them, what the hell we were supposed to do. There were only 40 of us.”

Eventually, they did find the enemy.

“My memory tells me they fired 1,100 rounds of 155 millimeter and two hundred rounds of a sort of smaller gun. Think about that. Fourteen hundred of these shells are going down and this whole thing went on for about three hours. At the end of it there were eight dead and something like 16 wounded of 40 people. To watch that stuff up close is mind altering to tell you the truth and a little bit life altering. I’m loath to say exactly what alteration resulted, except that you have an idea of however bad things get in the future they are not going to be as bad as this. You can have a bad hair day, but it ain’t that.”

After recovering from a grenade wound, Mr. Just returned to the field, staying in Vietnam for 18 months. When he came back to the States he continued to cover politics for the Washington Post but eventually left the newspaper business to focus on writing novels, publishing a new one every three or four years by focusing on one word after another. He described the process as like playing solitaire or a game of patience.

“You sit around for a few hours and then write a sentence. Then in a few more hours you write a second sentence. Then you rewrite the first sentence to fortify the second sentence. This goes on all day long until late afternoon. Then at the end of the day you erase all the adverbs.”

Deanne Urmy, who edited several of Mr. Just’s novels during the last 10 years for Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, was one of the first to see the results.

“The manuscript would arrive in typescript, smelling of smoke,” Ms. Urmy said, describing the old-fashioned way Mr. Just continued to work, banging out his novels on a typewriter, a pack of Camel cigarettes always nearby.

Ms. Urmy said she never had to do much of anything with the manuscript, describing the editorial relationship as one of bliss.

“It was mostly a matter of having wonderful conversations over what he had created,” she said.

“He was a deeply ethical man,” she continued, “and there was no one I loved making laugh more than Ward Just. And he laughed so easily.”

Mr. Just first visited the Vineyard in his twenties and then came back in his forties to give it a closer look. “Specifically Lambert’s Cove stuck in my mind. I just loved the look and shape, the sickle shape of Lambert’s Cove Beach,” he said in an interview with the Vineyard Gazette.

He and Ms. Catchpole bought a home on Lambert’s Cove in 1982 and a few decades later moved to Vineyard Haven. Over the years their circle of friends on the Vineyard continued to grow. Jules Feiffer remembered his first encounter.

“We met on the beach,” Mr. Feiffer said. “They had a blanket and a towel and some wine and they offered me some and I didn’t want to be rude. And it went on like that for decades. Ward was one of the great companions of all time. And that doesn’t even say half as much. Together we solved so many of the world’s problems, the solutions of which we couldn’t remember the next day.”

Rose Styron recalled how whenever she invited Mr. Just to dinner she would always arrange the seating so he would be next to her.

Kib and Tess Bramhall became friends soon after Mr. Just and Ms. Catchpole moved to the Vineyard full time.

“You never knew when his books ideas would come and neither did he,” Mr. Bramhall said. “They just emerged from his imagination and daily moments.”

Mr. Bramhall described a time when they were playing ice hockey on a pond and Mr. Bramhall tapped the ice with his hockey stick, which took Mr. Just back to his Chicago youth where his father had done the same thing.

“That became a scene in An Unfinished Season,” Mr. Bramhall said.

For many years Davis and Betsy Weinstock, along with Anthony Lewis and the Hon. Margaret Marshall, spent New Year’s Eve at the home of Mr. Just and Ms. Catchpole.

“It was limited to a small number of people so we could just talk,” Mrs. Weinstock said. “We always felt in each other’s company that all was well.”

“There are always losses,” she added. “But this is a big one. Ward holds a unique place in the hearts of many people.”

Mr. Weinstock remembered many get-togethers in addition to New Year’s Eve. “Red wine was always a serious component, oysters were omnipresent. He was a great companion, really the best company.”

The Vineyard did not feature in Mr. Just’s novels, but it was where he found the space to return again and again to the subjects dear to his heart, including the events he covered in Washington and the newspaper business, which was the subject of his final book The Eastern Shore, an elegiac look at the industry from a writer who, as the saying goes, had ink in his veins from the very start.

“Lucky is the person who really discovers what they want to do and they have the means to go ahead and do it,” Mr. Just said in an interview with the Gazette. “So I’ve led a very fortunate life.”

In addition to Ms. Catchpole, he is survived by two daughters, Jennifer Just of Woodbridge, Conn., and Julia Just of Brooklyn, N.Y.; a son, Ian Just of Arlington, Mass.; and six grandchildren.

A burial service at Lambert’s Cove Cemetery will take place Jan 5 at 2 p.m.

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »