Nelson Bryant, a celebrated New York Times outdoor columnist and Army paratrooper who parachuted into Normandy on D-Day during World War II, died Saturday at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital. He was 96.

An avid sportsman who hunted, fished and knew every inch of the Island’s back woods, marshlands, beaches and surrounding waters, Mr. Bryant had lived in West Tisbury and close to the land for nearly all his long life. Blunt-spoken, salty and smart, he recalled the war years with vivid clarity, even more than half a century after they had ended. He was one of the last surviving Islanders of the Greatest Generation, along with his war colleague Ted Morgan, who died in November 2019.

“Sometimes I’m haunted by that goddamned war. Night after night after night,” he told the Martha’s Vineyard Museum’s oral historian Linsey Lee in a 2010 interview.

“I have a healthy respect for danger. I’m very leery of things, and think a lot about them. [But] . . . my country was at war. I detested Hitler, what was going on all over the world, and I decided that I ought to do my part. And so I tried to pick the hardest thing I could find.”

He was born on April 22, 1923, in Long Branch, N.J. His family moved to the Vineyard in 1933 during the Great Depression.

He attended schools in West Tisbury and Tisbury and finished high school at the Norfolk School for Boys in Connecticut.

He was accepted at Dartmouth College and enrolled in 1942 for a summer semester.

“It was interesting, but not very rewarding intellectually because all of us freshmen ate in one place, and we all got ill with a virulent disease,” he recalled in the interview with Ms. Lee. “Most of the time I spent in the infirmary. But anyway . . . the war was going on and I said, I can’t sit and let this go by.”

Dartmouth had a Naval Reserve Officer Program. He tried to enroll but couldn’t get in because he had been born blind in his right eye.

So he volunteered for the draft and joined the Army. He tested into Second Signal Service Battalion.

“It was a high-flying intelligence outfit, decoding and that sort of thing,” he recalled. “But I had nothing to do with words or decoding. My job was to work with the supply sergeant and hand out clothes to all the people that were studying how to break codes.” He continued:

“This was Army. And it was boring. As a matter of fact it was so boring that I memorized the names of all — let’s say there were 100 men. Just for something to do. For instance, I still remember the last one. It was Frederick W. Zander, and his identification was 12125356.”

He was keen to join the Airborne despite his eyesight, and found a way to get in by reading the eye test on both sides with his good eye.

He eventually qualified to become a paratrooper and excelled at rifle training, partly thanks to a lifetime spent hunting on the Vineyard, even though he could only shoot from his left side. He joined the 82nd Airborne Division’s 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

“I found my first jump unpleasant,” he recalled in the interview with Ms. Lee. “I was scared. But I had wanted to do something that was difficult. I didn’t want to hand out socks and shoes. I didn’t want to be a cook in a kitchen. I wanted to be a frontline soldier.”

He jumped into Normandy the night before D-Day and jumped into to Holland and in the Battle of the Bulge. He left Sissonne, France, after he was wounded.

In a 2011 interview with the Martha’s Vineyard Magazine he recalled the incident.

“I was a sort of a scout,” he said. “I had a working knowledge of French from the Vineyard Haven school, where Lena McCoy had taught me, and I had taken French that one semester at Dartmouth, so I was taking patrols out at night because I could talk a little with the French people. We’d go to farmhouses and try to find out what the farmers knew about the Germans. I was on one of these patrols and a machine gun up on a hill was fired. It killed my fellow soldier and a bullet went through my right chest. I was just lying there on the ground and one of our patrols came by me. Then it came back and Maj. Shields Warren, the officer in charge of the patrol, stepped over me and said, Nelson, if you don’t want to be taken prisoner, you’d better cut out of here. And so, with the help of a buddy, I got up. I spent five days after that hidden in a hedgerow with others who were wounded, and then an ambulance took me to a field hospital on the English Channel.”

In a remarkable story, two years ago a Dutch man found a knife in his attic that Mr. Bryant had lost during a jump, and tracked him down through the internet to return it to him.

When the war ended, Mr. Bryant returned to the Vineyard and married Jean Morgan from Edgartown. They had four children. He worked briefly at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution before returning to Dartmouth on the GI Bill. He received a fellowship to study English at the graduate level at Brown University, but left after finding that academic life didn’t suit him.

He worked for a few New England newspapers, serving as managing editor of the Daily Eagle in Claremont, N.H., but was drawn back to the Vineyard in 1965 to work with his brother in law Bob Morgan who had started a dock-building business.

In the late 1960s a friend encouraged him to approach the New York Times after Oscar Godbout, the newspaper’s longtime outdoors columnist, had died.

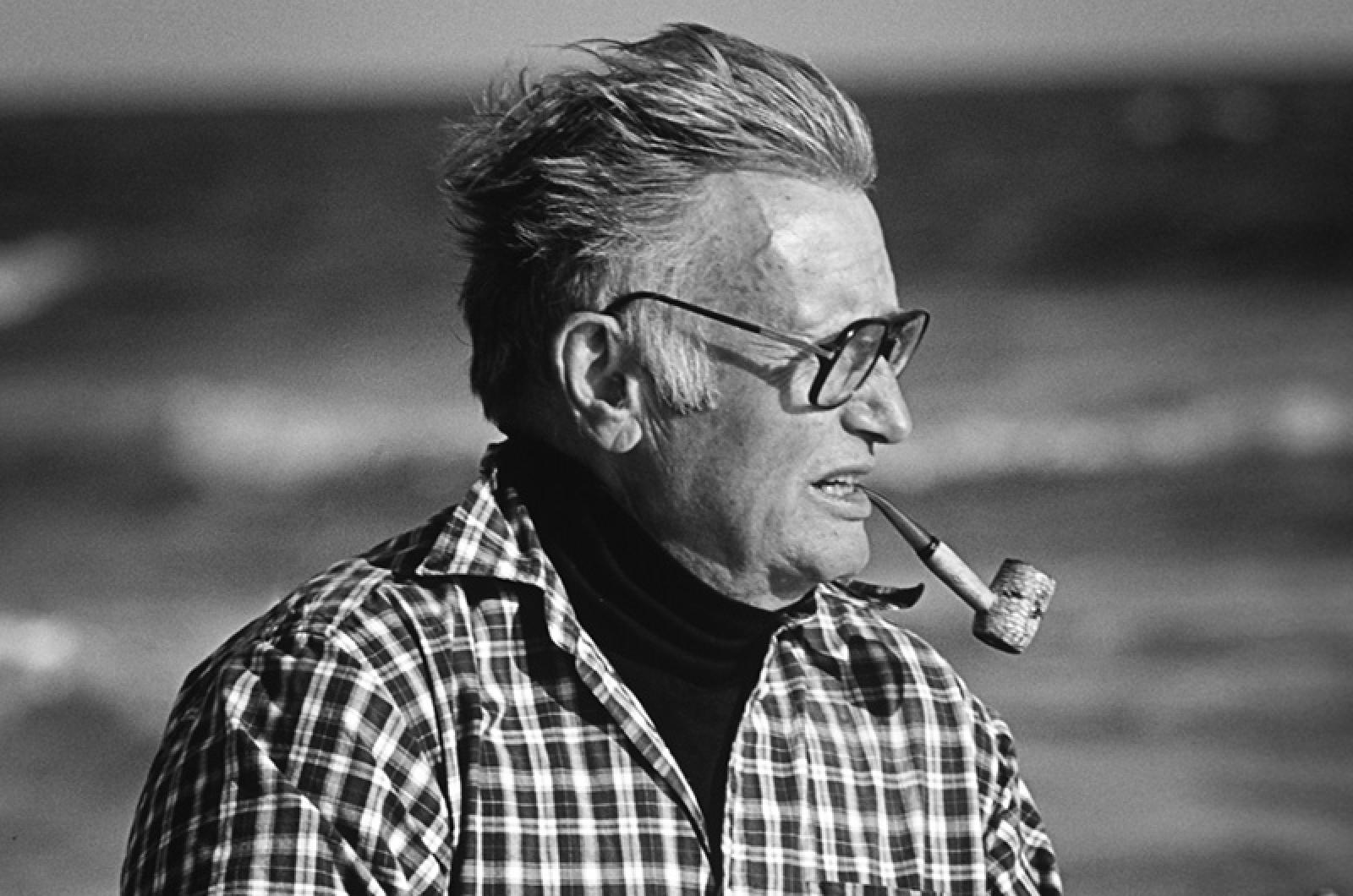

“So I wrote to the sports editor of the Times,” he recalled, “and I was asked down to meet with Turner Catledge, the managing editor, and Clifton Daniel, who was married to Margaret Truman. It really wasn’t much of an interview. I just sat there smoking my pipe and encouraging them to talk about themselves, though Catledge, who was a Southerner, did ask me if I knew how to kill a possum and promptly gave me a description. Anyway, they asked me to go home and write three columns and they’d pay me for them whether they used them or not.” He continued:

“Well, they hired me, but they wanted me to move to New York and with a young family, I said how in hell could I do that. I told them I’d have to have quite a pad in the city. It would have to be big enough for five canoes and 20 guns and 20 or 30 fishing rods and boxes of knives and tenting equipment and sleeping bags and decoys and a wife and four kids and an ailing mother. So it was agreed that I could keep the Vineyard as my home base.”

For the next 30 years he wrote three to five columns a week for the New York Times and did what he loved best: hunting, fishing and spending time outdoors. He traveled to Scotland to shoot grouse, to Alaska to fish for salmon and to Wyoming to hunt elk.

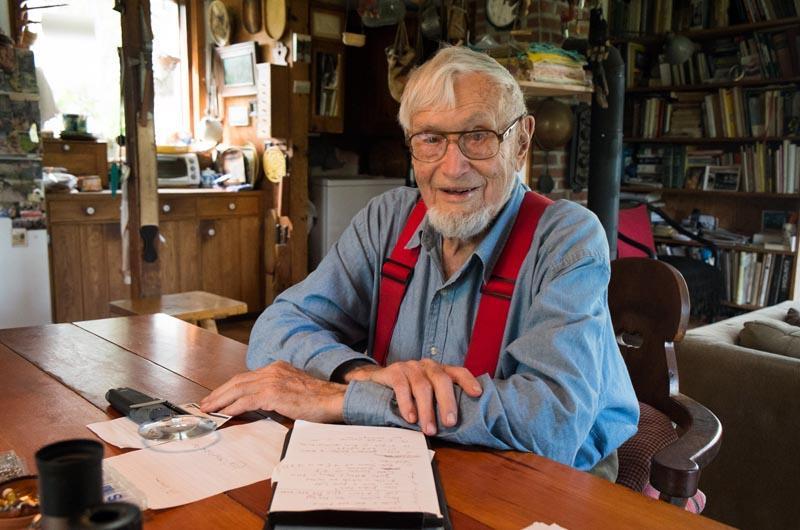

Divorced since the 1980s, in recent years he had lived behind his former family house in West Tisbury with his longtime partner and artist Ruth Kirchmeier, who survives him, surrounded by the trappings of his outdoor life. He cut his own firewood, grew a vegetable garden, hunted ducks and went oystering in the Tisbury Great Pond.

He authored books, including Fresh Air, Bright Water: Adventures in Wood, Field and Stream (1971); The Wildfowler’s World (1973, with Hanson Carroll); Outdoors, a collection of his columns (1990); and a memoir Mill Pond Joe: Naturalist, Writer, Journalist and New York Times Columnist (2014).

He contributed to the Gazette and the Martha’s Vineyard Magazine, and in his later years wrote for the Martha’s Vineyard Times.

Funeral arrangements are incomplete.

Comments (27)

Comments

Comment policy »